HASIDISM

HASIDISM

A NEW HISTORY

WITH AN AFTERWORD BY ARTHUR GREEN

DAVID BIALE, DAVID ASSAF, BENJAMIN BROWN, URIEL GELLMAN, SAMUEL C. HEILMAN, MOSHE ROSMAN, GADI SAGIV, AND MARCIN WODZISKI

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2018 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

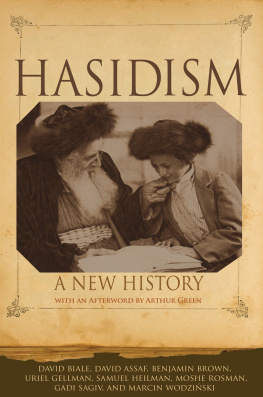

Jacket illustration by Shlomo Narinsky, A Hasid of the Chabad dynasty and his great-grandson in Hebron, 19101921. Photogravure. 8.713.5 cm. Copyright the Tel Aviv Museum of Art (Photo: Dima Valershtein)

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Biale, David, 1949 author. | Assaf, David, author. | Brown, Benjamin, 1966 author. | Gellman, Uriel, author. | Heilman, Samuel C., author. | Rosman, Murray Jay, author. | Sagiv, Gadi, author. | Wodziski, Marcin, author.

Title: Hasidism : a new history / David Biale, David Assaf, Benjamin Brown, Uriel Gellman, Samuel C. Heilman, Moshe Rosman, Gadi Sagiv, and Marcin Wodziski ; with an afterword by Arthur Green.

Description: Princeton ; Oxford : Princeton University Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017021879 | ISBN 9780691175157 (hardcover : alk. paper)Subjects: LCSH: HasidismHistory.

Classification: LCC BM198.3 .B53 2017 | DDC 296.8/33209dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017021879

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been published with the financial assistance of the Thyssen Foundation.

This book has been composed in Garamond Premier Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Figures

Maps

Tables

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

David Biale

THE STORY OF HASIDISM IS A SAGA OF extraordinary vitality and adaptability: from its origins in the eighteenth century, Hasidism confronted different challenges in a changing world and succeeded in reinventing itself to survive and flourish. Given its great importance to understanding Jews in the modern world, it is surprising that a comprehensive history of the movement from its eighteenth-century origins to the present day does not exist. Although it has been the subject of historical research for over a century, most of the scholarly as well as popular literature focuses on the eighteenth century and much of it is specialized in nature. Moreover, the fruits of the most recent research have yet to be synthesized in a new narrative of the history of this movement. Such a narrative must not only integrate a century of research but must also emphasize how Hasidism shaped modern Jewish history.

To tell this story requires vast knowledge and an approach that is less encyclopedic than analytic and synthetic. Thus this new history does not discuss every Hasidic court but instead identifies patterns of ideas and social structures. There is much that we do not know, since not every phase of the history of Hasidism has been as deeply researched as, for example, its eighteenth-century origins. In particular, the late nineteenth century, when the Hasidim began to migrate to Eastern European cities, is poorly understood. There is also a dearth of research on important aspects of twentieth-century Hasidism, particularly between the World Wars. A particular challenge is demographic: how to determine how many Hasidim there were in any given place and time. Census data is often fragmentary and unreliable, and numbers must be inferred indirectly. For all these reasons, this study must remain partly incomplete. But since Hasidism today is still highly vital and dynamic, the story of its evolution is itself unfinished.

This work represents an innovative collaboration of scholarsjunior and seniorfrom three countries. Given the division of Hasidism into many courts and dynasties, its geographical spread and intellectual diversity, a new history of Hasidism requires a team effort of researchers with different expertise and methodologies: intellectual and social historians as well as sociologists.

Our book could never have seen the light of day without the help of many individuals and foundations, and we are delighted to acknowledge these debts. The project owed its earliest formation to the Israel Institute for Advanced Studies (then under the auspices of the Hebrew University), which hosted a research group that included most of us, under the title of A New History of Hasidism, during the academic year 20072008, and, in 2010, brought together the first meeting of our team in Jerusalem. We thank the institute for this early support.

At the 2010 meeting, the group resolved to embark on a collectively authored work. To this end, we spent four summer residencies at the Simon Dubnow Institute in Leipzig, Germany, developing first a detailed outline, then complete chapter drafts, and finally intensive editing. Thus the manuscript went through peer review even before it was submitted to Princeton University Press. We therefore owe our greatest debt to the Simon Dubnow Institute, its director Dan Diner, and its academic staffSusanne Zepp, Jrg Deventer, and Arndt Engelhardtas well as its administrative staff and, in particular, Carina Roell. Our residencies at the Dubnow Institute were essential to the project, and the institute did a splendid job of making us welcome.

We have also benefited greatly from specialized assistance. Ariel Evan Mayse served as editorial assistant and contributed his vast knowledge to the project, editing the whole manuscript for content and style and the footnotes for accuracy and consistency. Elly Moseson provided research assistance in the first year of the project. Batsheva Goldman-Ida served as illustrations editor and made available to us her rich resources of visual material. We are also grateful to Maya Balakirsky Katz for her assistance with visual material from Chabad. Thanks to the Taube Foundation, Aleksandra Sajdak in Warsaw assisted in the search for illustrative materials in Polish institutions. Waldemar Spallek of the University of Wroclaw, Poland, designed the maps. We are grateful to our colleague, Marcin Wodzinski, for generously making data available from his Atlas of Hasidism (Princeton University Press) for the production of our maps.

Our residencies in Leipzig were generously funded by two grants from the Fritz Thyssen Foundation. We were also privileged to receive a National Foundation for the Humanities Collaborative Research grant to support other parts of the project. And the Taube Foundation supported translations from Polish and illustrations with another generous grant. We thank all of them for their faith in this project.

We were ably assisted by four translators: from Hebrew by Sharon Assaf, Rachel Biale, and Saadya Sternberg; and from Polish by Jaroslav Garlinski.

Finally, we wish to acknowledge our debt to Ada Rapoport-Albert and Arthur Green, both among the greatest authorities on Hasidism today. Ada was involved with the project from its inception and participated actively in three of our summer residencies in Leipzig, helping to shape its form and content. She also generously read and criticized significant sections of the manuscript. Art was also involved with this project from the beginning and made some crucial contributions as it came to a conclusion. He wrote the sections on the thought of Dov Ber, the Maggid of Mezritsh, and Nahman of Bratslav. He also read critically the whole manuscript, thus serving as one more editorial voice. And he wrote the afterword, which sums up in a personal way the many pages that lie in front of you.

Next page