GERSHOM SCHOLEM

Gershom Scholem

Master of the Kabbalah

DAVID BIALE

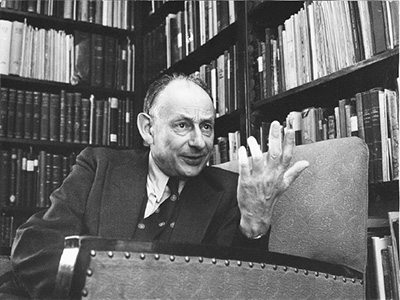

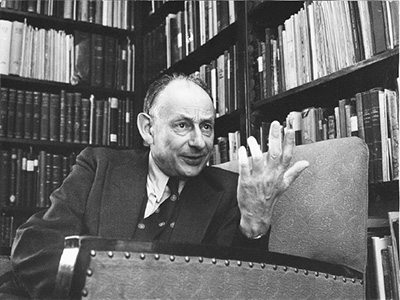

Frontispiece: Gershom Scholem in his library, 1962 (courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute, New York)

Copyright 2018 by David Biale.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Janson Oldstyle type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017959384

ISBN 978-0-300-21590-8 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ALSO BY DAVID BIALE

Gershom Scholem: Kabbalah and Counter-History

Hasidism: A New History (with David Assaf, Benjamin Brown, Uriel Gellman, Samuel Heilman, Moshe Rosman, Gadi Sagiv, and Marcin Wodziski)

Norton Anthology of World Religions: Judaism (editor)

Not in the Heavens: The Tradition of Jewish Secular Thought

Blood and Belief: The Circulation of a Symbol Between Jews and Christians

Cultures of the Jews: A New History (editor)

Eros and the Jews: From Biblical Israel to Contemporary America

PREFACE

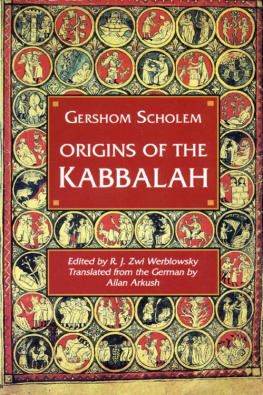

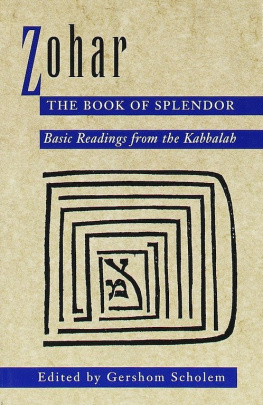

THIRTY-FIVE YEARS after his death, Gershom Scholem (18971982) continues to cast a long shadow over the world of Jewish thought. During his lifetime, he won wide acclaim for unearthing the sources of Jewish mysticism and messianism that other historians, convinced that Judaism was primarily a religion of reason, had ignored or despised. By restoring myth to Judaism, Scholem offered a radical new definition of his subject: the Jewish religion consists of paradoxes and contradictions, the rational and the irrational. Judaism has no dogmatic essence but is rather made up of whatever Jews have done or thought, no matter how outlandish or even demonic.

Scholems study of Jewish history thus broke out of the narrow confines of academic scholarship to provide a revolutionary way of thinking about Judaism. It is perhaps for that reason that at a time when the stars of other thinkers, famous in their day, such as Martin Buber and Franz Rosenzweig, have somewhat faded, Scholem has come to inhabit a brighter place in the Jewish firmament, as a luminary who continues to speak to us today. In 1973, when the English translation appeared of his monumental biography of Shabbatai Zvi (Sabbatai Sevi), the messianic figure from the seventeenth century, the reviews of the book, as one commentator has noted, had already diverged from the controversy that the Hebrew edition aroused in 1957. The reviewers of the English edition spent far less time discussing Scholems subjectfew were competent to do sothan talking about Scholem himself. He had become the subject.

Scholem also transcended the world of scholarship for other reasons. When he published his memoir From Berlin to Jerusalem in 1977, he put his stamp on a powerful narrative of modern Jewish history: by rejecting his bourgeois German Jewish roots and embracing Zionism, Scholem moved his idiosyncratic life choices from the margins to a central story. The German Jews, he alleged, had lived an illusion that was the GermanJewish dialogue, and only those few who became Zionists saw through this illusion. However, Scholems Zionism was anything but conventional, so his critique of the movement that brought him to Palestine in 1923 made his position both more interesting and more challenging. He defended the right of the Jews to create their own society yet criticized Zionism for failing to truly renew Judaism.

It is perhaps for all these reasonsintellectual, political, and culturalthat Scholems star has never faded. Remarkably, in the year that this book is making its appearance, no less than five other books dealing in whole or in part with Scholems biography are beingor have beenpublished (see the bibliographical note). This is more than at any other time since Scholems death and begs for an explanation. Certainly, as contemporary Zionism confronts a deep political and moral crisis, Scholems earlier reflections on the price that messianism might exact from modern Jewish nationalism seem apposite, even if formulated in a different reality. And his argument for an inclusive definition of Judaism also has resonance in an age when the battle between secularism and Orthodoxy has reawakened throughout the Jewish world. And so it is that contemporary writers of different persuasions find him urgently relevant.

In this book I do something that has not yet been done with respect to Scholem. The reader will find here an account of his life with an attempt to understand him from within. By using diaries and letters, I have tried to enter into his inner life and view him not only as a thinker and writer but also as a human being. At the same time, I have engaged with his most important writings in an effort to integrate them into his life. As such, this is the study of an extraordinary thinker: not an ethereal intellectual but a fully embodied person, filled with passions and paradoxes, much as he described Judaism itself.

GERSHOM SCHOLEM

1

Berlin Childhood

BERLIN, 1897. The city is exploding with commerce and culture, a far cry from the tiny Prussian capital of Frederick the Great. Between 1849 and 1871, when it became the capital of Bismarcks unified Germany, its population doubled, to 825,000. But the city was scarcely fit to serve as the capital of a new European power. In the 1870s, the socialist leader August Bebel noted that waste water from the houses collected in gutters along the curbs and emitted a truly fearsome smell. Within a few decades, however, city planners, engineers, and public servants would transform this primitive backwater into a gleaming, modern metropolis.

By 1897, the population of Berlin had again doubled, to 1.7 million. A year before, work had begun on a modern subway system, to be completed in 1902, which would take its place alongside an extensive network of street trams. Museums, opera, and theater crowned a rich cultural life. And the new Reichstag building, completed in 1894 with its impressive dome, sent a clear message of Germanys place in the modern world.

The Jews were an integral part of Berlins landscape at the end of the nineteenth century. When Moses Mendelssohn had entered via the Rosenthaler Gate in 1743, there were only about 2,000 Jews in the city. By 1871 the number had risen to 36,000. They had won most of their civil rights in mid-century, but with the emancipation of all German Jews in 1871, they were now the full equals of their Christian neighbors (they were, however, still barred from holding academic chairs as well as high offices in government and the military). In business, the professions, and the arts, in particular, they were represented often beyond their numbers in the population. By 1897, the Jewish population of Berlin had swollen to 110,000, the second-largest Jewish community (after Vienna) west of Warsaw. The community boasted recently built Reform synagogues, often in the Moorish style, but there were relatively few of the Orthodox Jews more commonly found in the rural communities farther east.

Next page