BOLLINGEN SERIES XCIII

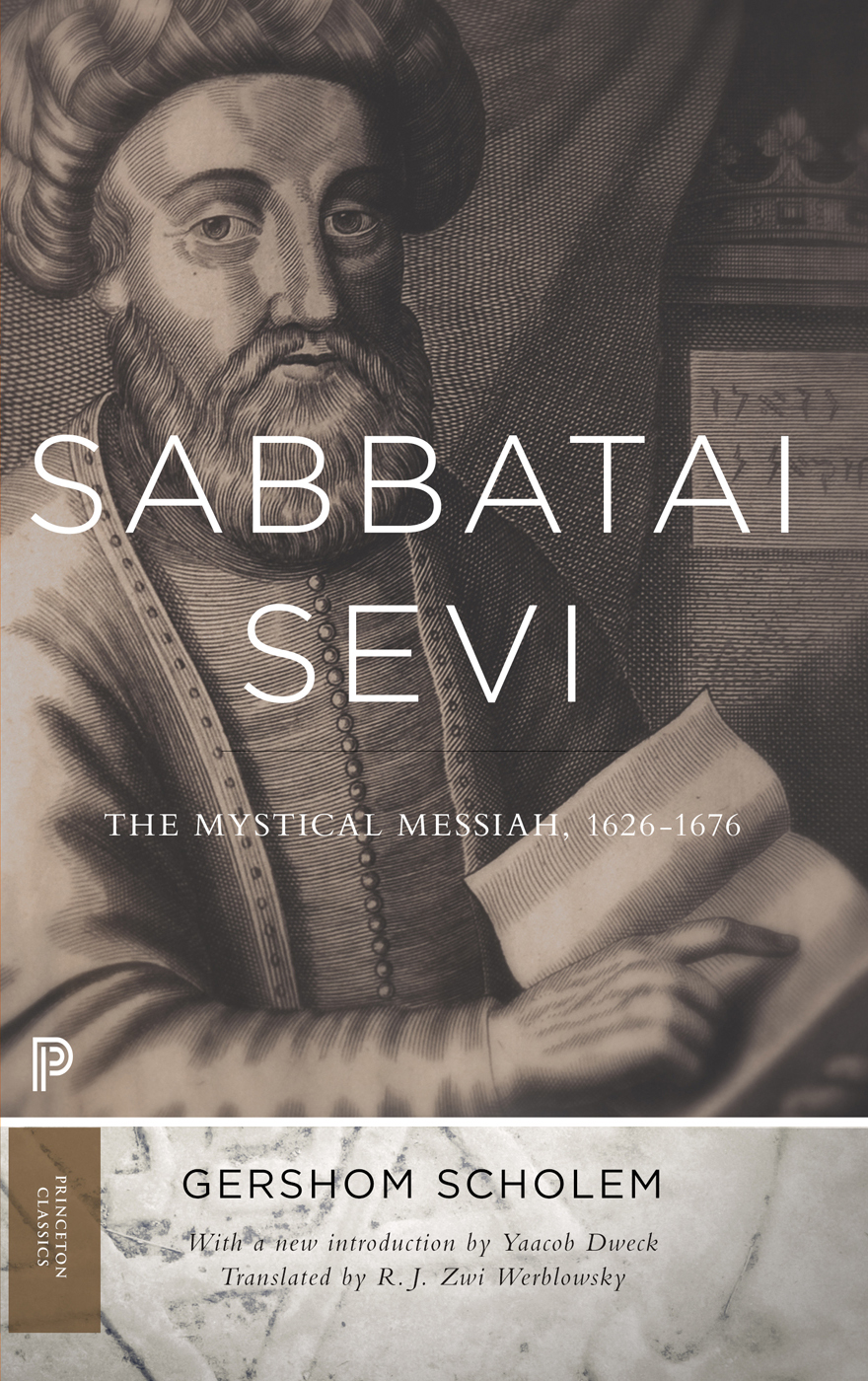

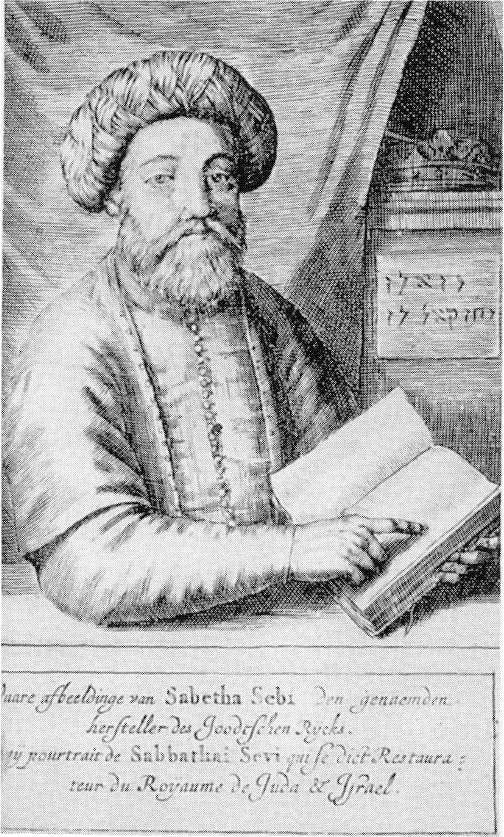

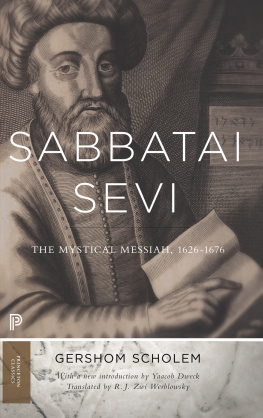

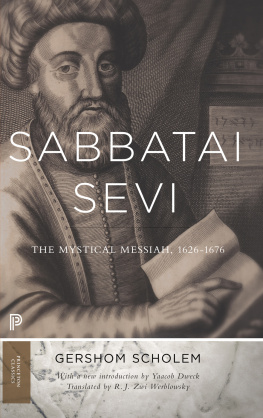

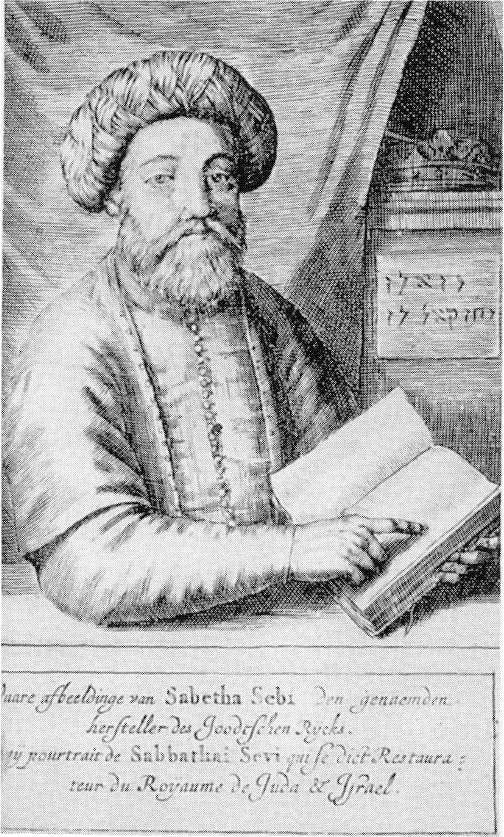

True Portrait of Sabbatai evi, sketched by an eyewitness in Smyrna, 1666. From Thomas Coenen, Ydele Verwachtinge der Joden

(Amsterdam, 1669)

GERSHOM SCHOLEM

SABBATAI EVI

The Mystical Messiah

16261676

With a new introduction by Yaacob Dweck

BOLLINGEN SERIES XCIII

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Copyright 1973 by Princeton University Press

Introduction to the Princeton Classics Edition copyright 2016

by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, NJ 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

All Rights Reserved

THIS IS THE NINETY-THIRD

IN A SERIES OF WORKS

SPONSORED BY BOLLINGEN FOUNDATION

A revised and augmented translation of the Hebrew edition: Shabbatai evi veha-tenuah ha-shabbethaith bi-yemei ayyav (Sabbatai evi and the Sabbatian Movement during His Lifetime), published by Am Oved, Tel Aviv, Israel, 1957.

First Princeton/Bollingen paperback printing, 1975

Princeton Classics edition, with a new introduction by Yaacob Dweck, 2016

Paperback ISBN: 978-0-691-17209-5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016945836

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Printed on acid-free paper.

press.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

TO MY WIFE FANIA

in remembrance of all those years

of common purpose

Paradox is a characteristic of truth. What communis opinio has of truth is surely no more than an elementary deposit of generalizing partial understanding, related to truth even as sulphurous fumes are to lightning.

From the correspondence of Count Paul Yorck von Wartenburg and Wilhelm Dilthey

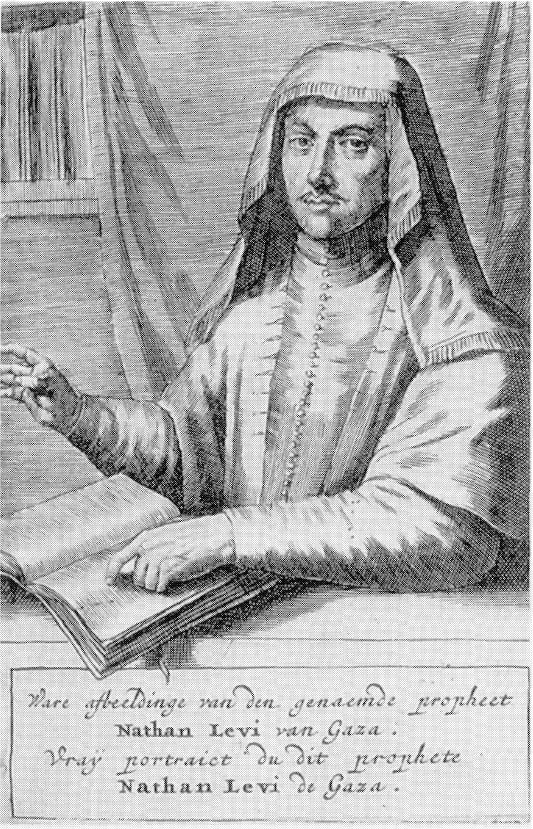

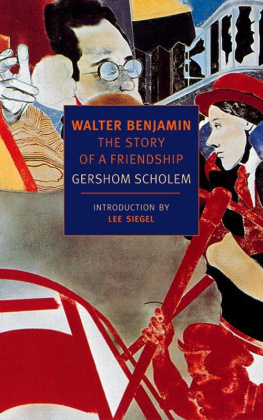

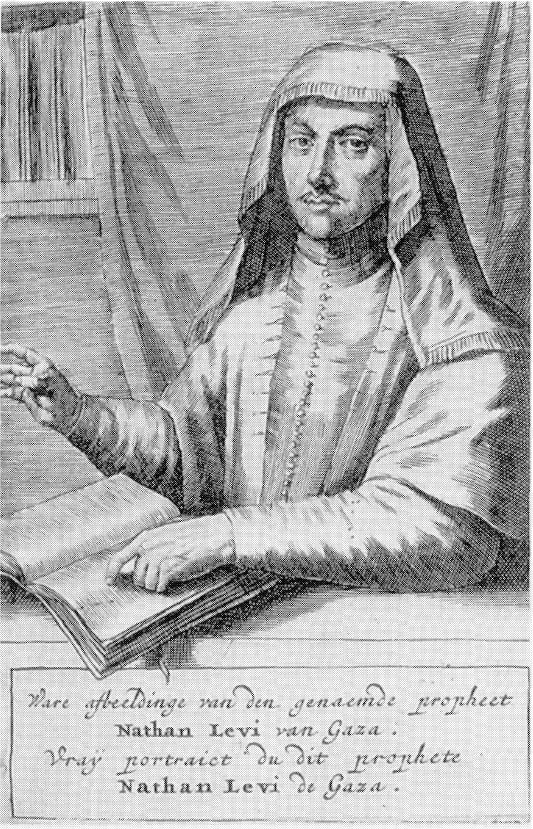

True Portrait of Nathan of Gaza, sketched by an eyewitness in Smyrna, 1667. From Thomas Coenen, Ydele Verwachtinge der Joden

(Amsterdam, 1669)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF PLATES

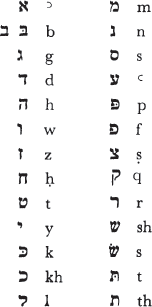

TABLE OF TRANSLITERATION

A measure of consistency in the transliteration of Hebrew has been aimed at, but absolute uniformity proved unfeasible. As a rule the system given here has been followed. For names and terms with a more or less established English spelling (e.g., kabbalah, Cordovero) the latter has been used instead of the philologically more accurate transcription. An outstanding example of the resulting inconsistency is the spelling of the name evi, although as a rule every Hebrew  is transcribed as b (e.g., iath Nobel evi). Biblical names are generally given in the form used in the Authorized Version. Modern Hebrew names or titles of books are given in the form in which they usually appear in print.

is transcribed as b (e.g., iath Nobel evi). Biblical names are generally given in the form used in the Authorized Version. Modern Hebrew names or titles of books are given in the form in which they usually appear in print.

PREFACE

I

A DETAILED HISTORY of the Sabbatian movement, the most important messianic movement in Judaism since the destruction of the Second Temple, has long been badly lacking in Jewish historiography. When, thirty-five years ago, I published my Hebrew essay Redemption through Sin, now available in English in my book The Messianic Idea in Judaism, my aim was to establish a basis for understanding the ideas which determined the character of the movement as it developed after the apostasy of Sabbatai evi, and particularly after his death. But direct contact with the sources has made me realize that historians have never done justice to this great and tragic chapter in Jewish history, either because they lacked the knowledge or because they lacked even the wish for knowledge. In my innocence I assumed that we at least had adequate factual information about the messianic outburst until the apostasy of the messiah, about the life of Sabbatai evi, and about the development of the movement before it reached its crisis. All that I needed to do, so I thought, was to provide the accurate historical perspective which was so noticeably absent from the existing literature. But it became clear that even this expectation was much too optimistic. As I became more deeply involved with the sources, I became convinced not only that important and vital sources had escaped the eyes of previous scholars, but that even those sources which had been used were often not correctly interpreted. I myself was surprised by the wealth of unknown material that I uncovered which shed new light on all phases of Sabbatai evis career, and it soon became apparent that the entire picture of the movements history had to be reconstructed from the start. Since then I have published a series of sources and studies relevant to the subject. Moreover, others have followed suit and have undertaken research in this neglected field. As a result of all this spadework a comprehensive and lively picture of the entire Sabbatian movement began slowly to emerge.

The present work is a synthesis that offers a comprehensive history of the movement up to the deaths of Sabbatai evi and of his prophet, Nathan of Gaza, and I hope that I will be able to complete at a later time a sequel covering the history of Sabbatianism in its various forms after the death of Sabbatai eviits conflicts, its metamorphoses, and its reverberations.

In this book I hope to prove that those sources which historians have tended to regard with particular contempt are the very sources which can make an essential contribution to an understanding of the period. What I have in mind are the documents of kabbalistic literature and the theological writings of the followers of Sabbatai evi. This literature has not been considered worthy of the attention of enlightened Jews (among whom one is inclined, of course, to include historians). Most of the heretical literature of the Sabbatians was destroyed during the persecution of the sectarians in the eighteenth century, and it has been virtually unknown that important parts of it survived. Half-articulated mutterings about mystical secrets, symbols, and images, all rooted in the world of esoterica and in the abstruse speculations of the kabbalists, became transformed, in my eyes, into invaluable keys to an understanding of important historical processes and into matters worthy of profound analysis and serious discussion. Sources and documents of this kind, which formerly found no place in historical literature, receive as much attention in the present book as do other archival documents, manuscripts, and broadsheets of all kinds, among which I have also found much new information. Often one type of source sheds light on another. Only by combining and analyzing all kinds of sources in the light of historical criticism can one gain a true picture of the age.

I have written this book on the basis of a particular dialectical view of Jewish history and the forces acting within it. But from the start more than just this view has been at work, guiding my presentationthe view itself is the outcome of a constantly renewed immersion in the sources themselves. I have not hesitated to change the opinions I expressed in earlier publications on specific points when renewed consideration of the sources required a new interpretation of the documents or of the historical processes reflected in them. I do not hold to the opinion of those (and there are indeed many of them) who view the events of Jewish history from a fixed dogmatic standpoint and who know exactly whether some phenomenon or another is Jewish or not. Nor am I a follower of that school which proceeds on the assumption that there is a well-defined and unvarying essence of Judaism, especially not where the evaluation of historical events is concerned. The internal censorship of the past, particularly by rabbinical tradition, has tended to play down or to conceal many developments whose fundamentally Jewish character the contemporary historian has no reason to deny. We are frequently as surprised by the level of vitality inherent in these developments as we are by their boldness and radicalism of thought. The last two generations have had their eyes opened and have been able to perceive the spark of Jewish life and the constructive aspirations even in phenomena which Orthodox Jewish tradition has denounced with full force.

Next page

is transcribed as b (e.g., iath Nobel evi). Biblical names are generally given in the form used in the Authorized Version. Modern Hebrew names or titles of books are given in the form in which they usually appear in print.

is transcribed as b (e.g., iath Nobel evi). Biblical names are generally given in the form used in the Authorized Version. Modern Hebrew names or titles of books are given in the form in which they usually appear in print.