Copyright 1971 by Schocken Books Inc.

Foreword copyright 1995 by Arthur Hertzberg

All rights reserved

under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

Published in the United states by Schocken Books Inc., New York.

Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Michael A. Meyer translated the following essays from the German: Toward an Understanding of the Messianic Idea, The Crypto-Jewish Sect of the Dnmeh, Martin Bubers Interpretation of Hasidism, The Tradition of the Thirty-Six Hidden Just Men, The Star of David, The Science of Judaism, At the Completion of Bubers Translation of the Bible, On the 1930 Edition of Rosenzweigs Star of Redemption, The Politics of Mysticism, and parts of Revelation and Tradition as Religious Categories.

Hillel Halkin translated Redemption Through Sin from the Hebrew.

See also Sources and Acknowledgements, .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Scholem, Gershom Gerhard, 1897

The messianic idea in Judaism and other essays on Jewish spirituality/Gershom

Scholem ; new foreword by Arthur Hertzberg.

p. cm.

Previously published: New York: Schocken Books, 1971. With new foreword.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-307-78908-2

1. MessiahJudaism. 2. JudaismHistory. I. Title.

BM615.S33 1995

296.33dc20 95-8425

v3.1

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Gershom Scholem was the master builder of historical studies of the Kabbalah. When he began to work on this neglected field, the few who studied these texts were either amateurs who were looking for occult wisdom or old-style Kabbalists who were seeking guidance on their spiritual journeys. His work broke with the outlook of the scholars of the previous century in Judaicadie Wissenschaft des Judentums, the Science of Judaismwhose orientation he rejected, calling their disregard for the most vital aspects of the Jewish people as a collective entity a form of censorship of the Jewish past. The major founders of modern Jewish historical studies in the nineteenth century, Leopold Zunz and Abraham Geiger, had ignored the Kabbalah; it did not fit into their account of the Jewish religion as rational and worthy of respect by enlightened minds. The only exception was the historian Heinrich Graetz. He had paid substantial attention to its texts and to their most explosive exponent, the false Messiah Sabbatai Zevi, but Graetz had depicted the Kabbalah and all that flowed from it as an unworthy revolt from the underground of Jewish life against its reasonable, law-abiding, and learned mainstream. Scholem conducted a continuing polemic with Zunz, Geiger, and Graetz by bringing into view a Jewish past more varied, more vital, and more interesting than any idealized portrait could reveal.

Some of his contemporaries muttered on occasion that Scholem overvalued the Kabbalah by making it the equal of the Halakhah, the Biblical-Talmudic legal tradition that defined Jewish practice, but no one challenged his insistence that mysticism and the Kabbalah had been a major, and undervalued, force in Jewish history. The overt disagreements with Scholem were about some of the results of his studies. Almost all of the scholars in the field were his students or, in his later years, students of his students. They revered Scholem for his genius, were in awe of his enormous learning, and feared the fierceness with which he defended his views. The wide-ranging debate with Scholems views has flourished, in innumerable articles and many books, only in the years since his death in 1982. Toward the end of his life, speaking to his friends with a mixture of ruefulness and objectivity, Scholem predicted that this revisionism would happen. There was enough pain in such conversations, when he was facing his own mortality, that I, for one, did not dare remind him that he himself had begun as an historical revisionist, challenging the very foundations of the work of the Jewish historians of the preceding century, and that once, in an earlier conversation when his spirit was more buoyant, he had quoted Nietzsches remark that the truest homage that the disciple pays the master is to betray him.

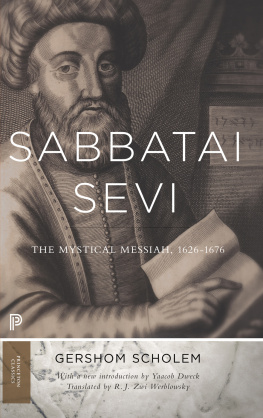

Even so, despite Scholems overwhelming authority, there were two issues on which lances were broken with him in his own lifetime. One subject of contention was Hasidism. Scholem contended that the turn to Jewish modernity began with the Sabbatians, who dared to change the Halakhah and even to overthrow it, and not with the Hasidim, who obeyed the inherited Jewish law. Scholem had insisted (the essay appears in this collection under the title The Neutralization of the Messianic Element in Early Hasidism) that the Hasidim systematically moved away from the Messianic impulse in the Kabbalah of Rabbi Isaac Luria. He argued that the early Hasidim did not seek to hurry the redemption of the Jewish people and of all the world; their central concern was personal communion with God, and such communion was as available in Poland as in the Holy Land. Why had the early Hasidism abandoned Messianism? Scholem answered that they were distancing themselves from Sabbatai Zevi. The sect of his followers had remained much more powerful and troubling than anyone before Scholem understood. The Jewish community felt threatened by the persistence of such Messianic activism. Therefore, the early Hasidim became quietists. Scholems insistence that Hasidism had broken with the Messianic impulse in the Lurianic Kabbalah was directly opposed to the view of the historian Ben Zion Dinur, a colleague at the Hebrew University. Dinur was convinced that Messianism was a central element in the thinking of the Baal Shem Tov and his immediate disciples, who had founded Hasidism in the second half of the eighteenth century. But Dinur was an ideologue who saw all of Jewish history as pointing to the Zionist return to the land of the ancestors. Scholem took more seriously the dissent of Isaiah Tishby, his first major disciple, whom he had trained to become a specialist in the texts of the Kabbalah and of Hasidism. Tishbys views were more nuanced than Dinurs, but they were more upsetting, because they were based on an independent reading of the very literature that Scholem himself had used. Tishby concluded that the early Hasidim had softened the overt expressions of Messianism but had not abandoned this Lurianic teaching. Tishby insisted, contrary to Scholem, that the Messianic remarks in the early Hasidic texts were not routine formulas; they reflected the continuing, living force of activist Messianism. Some of the early Hasidic writers had even predicted dates, very soon, for the coming of the Messiah.

Another significant debate with Scholem in his own lifetime was over the origins of modernity. In Scholems view, the modern era in Jewish history began with two revolts against the accepted, prevailing norms of Jewish life in earlier centuriesthat Jews must obey the prescribed Halakhah, and that they dare take no action to force the hand of God to bring the Messiah. In several of the essays in this volume he asserted that the modern era in Jewish history began with the breaking of the barriers of conventional faith and practice by Sabbatai Zevi and his prophet, Nathan of Gaza. Their followers went underground within the Jewish community or followed Sabbatai Zevi and converted to Islam, keeping secret their identity as Jewish followers of this Messiah. Whether wrapped in a tallit in the synagogue or wearing a fez in the mosque, the adherents of Sabbatai Zevi kept alive a Jewish teaching of rebellion against the law, and even of the holiness of sin. The Sabbatians took these actions because they insisted that the law of the Bible and the Talmud were intended for pre-Messianic times. By living beyond the law, they were actively inaugurating the new age of redemption. Thus the Sabbatians justified, on Kabbalistic grounds, a new Judaism, one which defied the law and was contemptuous of passivity. In Scholems account, even modern Zionism itself harks back to the activist Messianic impulse of Sabbatai Zevi. Jewish modernity in all its major parts thus began in the aftermath of a false Messianism that appeared late in the seventeenth century.