CONTENTS

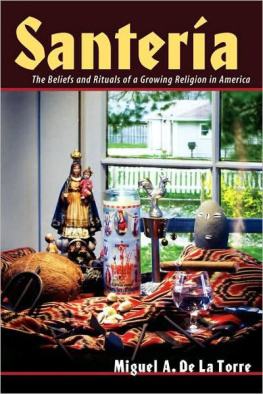

Since the publication of this book in 1988, I have had the opportunity to speak with priests and priestesses of santera from all over the United States. Perhaps the most impressive thing that has been brought home to me is the increasingly public nature of the religion as more and more people come forward to identify themselves with it. For most of the history of santeria in its diaspora, leaders have been concerned with defining the tradition solely for themselves and their own initiates. In the United States during the past ten years, however, a number of leaders have felt called upon to develop institutions and texts to present the religion to a variety of outsiders, ranging from municipal authorities to news media to spiritual seekers. While the community that welcomed me in the Bronx in the late 1970s and early 1980s was devoted to protecting its privacy, other individuals and communities have since taken on public roles as clearinghouses for information about the religion and as organizers of cultural activities for the wider community.

This institutionalization of the religion may have something to do with the nature of the immigrant experience in the United States. The leadership of the community described in this book was composed of immigrants from Cuba, who, for a variety of thoughtful reasons, were reluctant to draw attention to their practice of a nonJudeo-Christian religion in this country. Younger leaders, many of them American born, have been more outspoken in asserting their rights to the free exercise of religion in America and they have had to defend them against considerable opposition from municipal and ecclesiastic authorities. The most notable example of the perils of the public practice of the religion is the case of Hialeah, Floridas Church of Lukumi Babaluaye. Incorporated as a church, this community lost an extended challenge in the courts, where they sought the right to slaughter animals in the prayerful manner prescribed by tradition.

The news medias coverage of santera has focused its attention exclusively on the slaughter of animals or the practice of the religion by drug dealers. It has never been their interest to examine the religions import for the hundreds of thousands of Americans for whom it is a part of daily life. When grisly evidence of the ritual murder of human beings was unearthed in Matamoros, Mexico, in the spring of 1989, reporters and law enforcement authorities were slow to accept that such murders were not extensions of the ritual slaughter of animals for food. It came to light that the killers in Matamoros were not inspired by their associations with an African religion, but with a Hollywood image of one. They testified that they repeatedly watched a tape of the feature film The Believers, which characterizes African religions as cults of human sacrifice.

These sensationalized news stories have fueled debates in municipalities in Florida and California concerning legislation aimed specifically at practitioners of santeria and other traditions that slaugher animals under ritual conditions. In the face of these new challenges, priests and priestesses have felt it necessary to provide a measure of reliable information to authorities and media and to bring the religion into the light of public scrutiny.

Yet this new public posture presents a number of difficulties for the tradition. Beyond the reprisals of religious intolerance, one of the problems in bringing the religion before the public is the commitment of the tradition to oral teaching. Knowledge in the religion is based on initiation. Only those who carry certain initiations are sanctioned to attend certain ceremonies, learn certain ritual information, or know the increasingly esoteric meanings of rhythms, songs, greetings, gestures, foods, and herbs. This emphasis on secrecy has the positive value of preserving the personal transmission of teachings, but it continues to fuel the suspicions of outsiders about illegal or immoral acts. Thus, the religion is threatened both by becoming too public and remaining too secret. As the religion becomes institutionalized, it faces losing the controls and benefits of the esoteric transmission of knowledge. If it remains secret, it suffers the harassments of civil authority in ignorance.

One example of this dilemma is the development of texts for the religion. Authoritative texts are public in that all may have access to them, and they become the means to maintain discipline against charlatans, criminals, or fools. Yet they obviate one of the signal benefits of the religion, the contextualization of the teachings in the face-to-face transmissions of initiation ceremonies. As the religion in the United States moves from strictly oral to some forms of written transmission, the issues of the authority of the texts become paramount. Until recently anyone seeking information on the tradition either had to commit to some level of initiation or had to rely exclusively on texts written by outsiders to the tradition. Recognizing the role that her books had begun to play as ritual texts, the late Cuban folklorist Lydia Cabrera wrote a Spanish-language primer with the imperative title Koeko Iyawo , or in English Learn, Novice! I have been flattered when a number of leaders have told me that they use Santera: African Spirits in America in instructing their English-speaking neophytes.

But the tradition is ready to move beyond outsiders images of it, no matter how well intentioned they might be. Priests and priestesses are endeavoring to publish their own texts, both as practical guides for their own communities and as educational texts for outsiders. Notable among these is the work of Ysamur Flores, Julio Garcia, Babalorisha John Mason, Philip John Neimark, Oba Oseigeman Adefunmi of Oyotunje, Cecilio Perez, Ernesto Pichardo, Miguel Ramos, and the Caribbean Cultural Center of New York.

The boundaries between scholar and practitioner are also being explored in universities as academically trained participants are producing new texts and interpretations of the religion. Robin Evanchuck and Ysamur Flores at UCLA, David Brown at Emory University, George Brandon at CUNY, and Raul Canizares at the University of South Florida are actively presenting new and more thorough visions of the religion to the scholarly community.

With the emergence of texts, the demarcations among the communities practicing the religion become more apparent. Each community becomes committed not only to its own way of ritual practice but also to certain texts with their own terms of self-description and orthography. The very name santera , with its implications of dependence on the Roman Catholic idea of saint, is rejected by many contemporary practitioners as trapping all discourse about the religion into discussions of syncretism and as overemphasizing the European elements of the tradition.

I chose the term santera because it was in use in the Spanish-speaking community I visited in New York. Santera is also the term used in the academic community I was joining, a usage given authority by the anthropological texts written in the middle decades of this century. If I were to be true to the new expressions of the religion, those being forged by the practitioners themselves, I might choose to speak of the orisha tradition, or more simply orisha , referring to the spirits that inspire the tradition.

Even these terms raise interesting issues of social linguistics and orthography. The word orisha comes from the Yoruba language of Africa and roughly translates as spirit in English. It is often rendered r s by those who know contemporary Yoruba in order to indicate the tonal quality of Yoruba vowels and variations in the Yoruba sibilants. These sounds are often anglicized by native English speakers and written as orisha , appearing this way in a number of texts including this one. Both the s and sh sounds are foreign to Spanish speakers so most of the orthographies rendered in Spanish texts reproduce the word as oricha .

Next page