2002 Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved

Copy Editor: Gregory McNamee

Production Editor: Ruth G. Thomson

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mason, Michael Atwood.

Living Santera : rituals and experiences in an Afro-Cuban religion / Michael Atwood Mason.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 1-58834-052-X (alk. paper) ISBN 1-58834-077-5 (paper : alk. paper)

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-58834-548-6

1. Santera. I. Title.

BL2532.S3 M272002

299.674dc21 2002021016

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication available

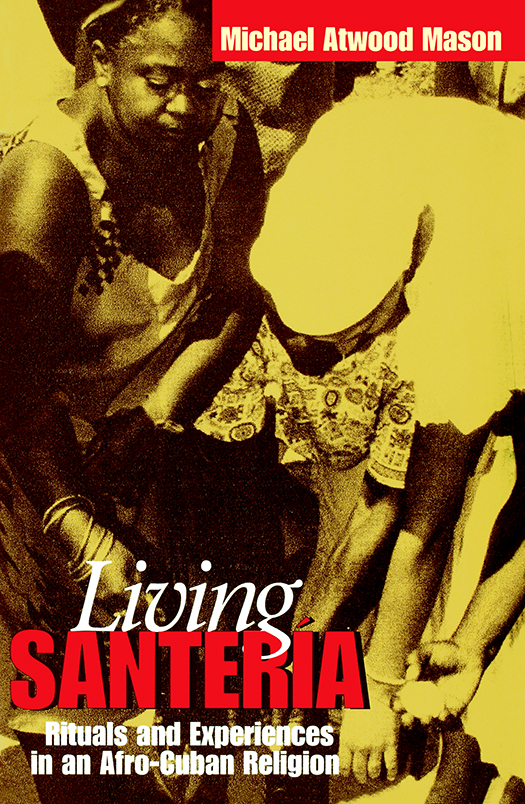

Cover photograph: Olokun ceremony, Habana del Este, 1999. David H. Brown. Used with permission.

v3.1

For David Brown, Katherine Hagedorn, and Ernesto Pichardo

fellow travelers in this mad adventure

Turn loose the voices, undream the dreams. Through my writing, I try to express the magical reality, which I find at the core of the hideous reality of America.

In these countries, the [Afro-Cuban] god Eleggu carries death in the nape of his neck and life in his face. Every promise is a threat, every loss a discovery. Courage is born in fear, certainty of doubt. Dreams announce the possibility of another reality, and out of delirium emerges another kind of reason.

What it all comes down to is that we are the sum of our efforts to change who we are. Identity is no museum piece sitting stock-still in a display case, but rather the endlessly astonishing synthesis of the contradictions of everyday life.

I believe in that fugitive faith. It seems to me the only faith worthy of belief for its great likeness to the human animal, accursed yet holy, and to the mad adventure that is living in this world.

[Galeano 1991:125]

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Living Santera

1 THE BLOOD THAT RUNS THROUGH THE VEINS

Defining Identity and Experience in Dilogn Divination

2 I BOW MY HEAD TO THE GROUND

Creating Bodily Experience through Initiation

3 MY PANTS ARE BLOODY

Negotiating Identity in American Santera

4 LIVING WITH THE ORICHAS

Ritual and the Social Construction of the Deities

5 IMAGINING POWER

The Aesthetics of Ach in Santera

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This adventure has been supported by many people who deserve special mention. From my parents I inherited both a passion for theology and religion that drives me and a pragmatism that sustains me.

At Indiana University, my research committeeespecially Richard Bauman and Michael Jacksonprovided me with guidance, encouragement, support, and freedom. Many administrators and support people at Indiana smoothed the way through numerous little glitches; my thanks to all of you. Several friends and colleagues made the time in Indiana more hospitable to me: Jana Giles, Sheila Guilfoyle, Soo Young Kim, Ona Kiser, Michael Nicklas, Jill Terry Rudy, George Schoemaker, and Rory Turner all listened to me talk through these ideas.

Ethnography, like all research, requires time and money. While at Indiana I received support from the Folklore Institute, African Studies Center, and the East Asian Studies Center. Summer fieldwork in 1990 in Washington, D.C., was supported by the District of Columbia Commission on the Arts and Humanities. My first field trip to Cuba was sponsored by the Cuban Studies Program at Johns Hopkins Universitys School of Advanced International Studies. Field trips in 1996, 1997, and 1998 were funded by the Smithsonian Institutions Office of the Provost and Scholarly Studies Committee. At the Smithsonian I have consistently received support in the form of time to work. Carolyn Margolis has been unwavering in her support. Through my work at the Smith, many colleagues have discussed aspects of this book with me: Mary Jo Arnoldi, Mark Auslander, Linda Heywood, Jake Homiak, Adrienne Kaeppler, Ivan Karp, Christine Mullen Kreamer, Robert Leopold, Marvette Prez, Fath Ruffins, Sonia Silva, Theresa Single-ton, Maria Sprehn Malagn, Barbara Stauffer, and John Thornton.

In Cuba, Rafael Leovigildo Lpez Valds and Enrique Sosa Rodrguez both befriended and guided me. Eusebio Leal Sprengler and the Office of the Historian of the City of Havana have facilitated my work on various occasions, as have Pedro Cosme Baos and the Municipal Museum of Regla. Other friends have made it possible to create the better part of a life in that relaxed and vivacious republic, which teeters between crisis and chaos: Antonio de Armas Arredondo, Elba Capote, Zoraida Garca, Alfonso Garca Clves, Ana Margarita Gil Delgado, Betsy Hall, Walkiria Lpez Pedroso and her daughter Gisela, the Lpez-Sabina family, Ernesto Rey Palma and his family, Antonio Quevedo Herrero, Remberto Reymundo Chaguayceda, Orlando Rivero Valds, Ival Rodrguez Gil, Roberto Rodrguez Menndez, Milagros Vaillant, Ernesto Valds Janet and his family, and Alberto Villareal.

Mi gentemy confidantsin the religion have accepted and taught me: Elia Clves, Eugenia Clves and her daughter Pancha, Raquel Fernndez Vigil, Sal Fernndez and his extended family, Judith Gleason, Geraldo Nimo Quintana, Lourdes Pedroso Clves and her son Juan Enrique, Norma Pedroso Clves, Santiago Pedroso Clves, and Humberto Prez have been among the most important. All of you have added to this project, and I thank you. My thanks also go to fellow santeros here in Washington, D.C., who live with me in this community, and to those around the world who have guided me at different times. My appreciation and affection go to the people who have come to my house to seek the orichas. Modupe o!

David Brown, Katherine Hagedorn, and Ernesto Pichardo have been loyal and consistent interlocutors for years, and each has had a hand in forming my thinking and this text.

Beyond the human, other entities have facilitated the creation of this text. Eleggu, Olocun, and Ochn all carried me in different ways. The slow, careful, and indefatigable Obatal proved to me that his proverb is true: Step by step you arrive far awayor in this case page by page. To them I say, Maferefn Oricha.

A version of , I Bow My Head to the Ground, appeared in a special issue of the Journal of American Folklore (1994) dedicated to bodylore.

NOTE ON LANGUAGE AND ORTHOGRAPHY

In this book, non-English words are italicized on their first appearance (where they are usually defined), as well as when they are used as terms. Italicized words are identified as either Lucum, the ritual dialect of the West African language Yoruba (see Olmstead 1953), or Spanish, the daily language spoken by most people who practice Santera. A few Yoruba words also appear. When a translation appears either in the text or in a parenthetical note, I have used abbreviations to indicate if the original word is Lucum (Lu.), Spanish (Sp.), or a combination (Lu., Sp.). In some cases I have used an English translation of a common term and then provided the Lucum and Spanish words in a parenthetical note.

Lucum does not usually have plural markers for nouns; thus, oricha (Lu. deity) can be both singular and plural. However, it is also common to hear Lucum words with Spanish endings; for example,