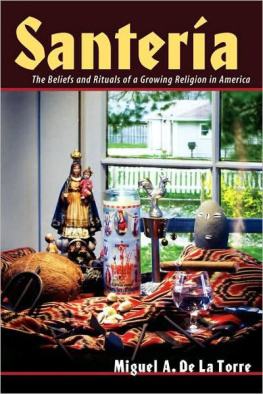

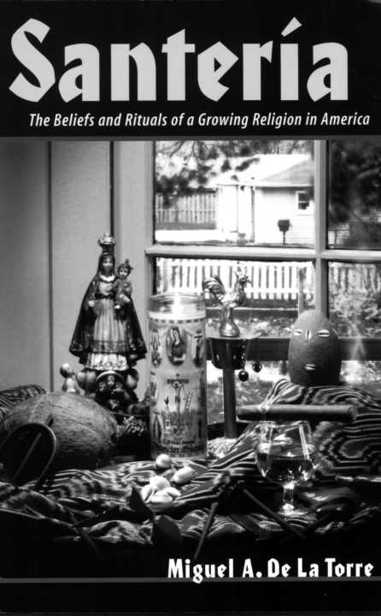

Santeria

San terla

THE BELIEFS AND RITUALS OF A

GROWING RELIGION IN AMERICA

Miguel A. De La Torre

To my son Vincent

May your curiosity about different cultures and religions increase with age as you apply yourself to reach your full potential in life

Contents

viii

X

xi

Tables

Figures

Preface

Throughout the i95os, the character of Ricky Ricardo in the popular television sitcom I Love Lucy entertained viewers with his signature song, Babalu-Aye. Desi Arnaz, playing Ricky, beat his conga drums and strutted around the stage to the amusement of a predominantly Anglo audience. The audience delighted in the Latin beat that came from Rickys drum, conjuring up images of a more exotic culture. But what most television viewers failed to realize was that Ricky Ricardo was singing to Babalu-Aye, one of the deities, called orisbas, of an AfroCuban religion known as Santeria. They were unaware of what the Latino community recognized: he was engaged in a sophisticated choreography that descended from the African civilization of the Yoruba, which was established long before Europe was ever deemed civilized.

Santeria, from the Spanish word Santo (saint), literally means the way of saints. This religious expression has been a part of the American experience for some time even though the majority of the dominant Euroamerican population fails to recognize its existence. Today, as since the days of slavery, it is probably the most practiced religion in Cuba. Over time the religion made its way to the United States, in part due to the 1959 Castro revolution, which over a period of forty-five years sent about a million Cubans north seeking refuge. With each forced migration - from Africa to Cuba and then from Cuba to the United States - believers brought their gods with them. But all too often, when compared to the normative Eurocentric manifestation of Christianity, Santeria is presented to the world through Hollywood movies and the news media as idolatrous, dangerous, or a product of a backward people. Some, operating from their anti-Hispanic prejudices, have used the religion to prove that the Latino community is indeed primitive. Others caricature the religion as simply something exotic to titillate the dominant cultures imagination. Missing from most analyses is a desire to respectfully learn about, and learn from, a religious expression that comes from the margins of society.

Regla de Ocha (Rule of Ocha), or Ayoba. But the average person who practices or who is familiar with this religion knows it as Santeria, and so I will continue to use this name throughout the book. Likewise, the priests of the faith are by some referred to as oloshas or babaloshas (for men) and iyaloshas (for women); however for the same reason they will be referred to as santeros or santeras.

Santeria originated when the Yoruba were brought from Africa to colonial Cuba as slaves and forced to adopt Catholicism. They immediately recognized the parallels existing between their traditional beliefs and the ones newly imposed on them. Both religions consisted of a high god who conceived, created, and continued to sustain all that exists. Additionally, both religions consisted of a host of intermediaries operating between the supreme God and the believers. Catholics called these intermediaries saints, while Africans called them orishas. In order to continue worshiping their African gods under the constraints of slavery, they masked their deities behind the faces of Catholic saints, identifying specific orishas with specific saints. These gods, now mani fested as Catholic saints, were recognized as the powerbrokers between the most high God and humanity. They personified the forces of nature and had the power to impact human beings positively or negatively. Like humans, they could be virtuous or exhibit vices, doing whatever pleased them, even to the detriment of humans. Like humans, they expressed emotions, desires, needs, and wants.

Basically, modern believers in Santeria worship these African gods, masked as Catholic saints, by observing their feast days, feeding and caring for them, carefully following their commands, and faithfully obeying their mandates. Complete submission, without question, is required of devotees, who are usually motivated by a mixture of fear and awe of the gods. Believers are not to question or argue with the gods or with priests of the faith. The only response is obedience. Disobedience implies a lack of respect that can lead to a total loss of guidance and protection. In return for obedience, believers learn the secrets by which natural and supernatural forces can be influenced and manipulated for their benefit. Rain can be summoned, seas calmed, death implored, fate changed, illnesses healed, and the future known, if such things will help individual followers come closer to their assigned destiny.

Santeria is comprised of an Iberian Christianity shaped by the Counterreformation and Spanish folk Catholicism, blended together with African orisha worship as it was practiced by the Yoruba of Nigeria and later modified by nineteenth-century Kardecan spiritualism, which originated in France and became popular in the Caribbean. But while the roots of Santeria can be found in Africas earth-centered religion, in Roman Catholic Spain, and in European spiritism, it is neither African nor European. Christianity, when embraced under the context of colonialism and/or slavery, has the ability to create a space in which the indigenous beliefs of oppressed groups can resist annihilation. And while many elements of Santeria can be found in the religious expression of Europe and Africa, it formed and developed along its own trajectory. In fact, different unique hybrids developed as the religious traditions of Yoruba slaves took root on different Caribbean soils. The vitality of Yoruba religiosity found expression through French Catholicism as Vodou in Haiti and New Orleans, and through Spanish Catholicism as Shango in Trinidad and Venezuela, Candomble in Brazil, Kumina in Jamaica, and of course, Santeria in Cuba.