RELIGION

IN

AMERICA

A COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE TO

FAITH, HISTORY, AND TRADITION

EDITED BY

HAROLD RABINOWITZ AND GREG TOBIN

Foreword by

Jane I. Smith

I. Roots and History

A. Introduction

F OR CATHOLICS, CATHOLICISM MEANS LIFE IN Christthat is, an encounter with Christ in the sacraments and through the teachings of the church. It implies a living relationship with Christ through a life of prayer and service. Such a living Catholicism has personal, social, historical, and even political implications, as demonstrated by the lives of the prominent people who have contributed to and continue to take part in the realization of Catholicism as the worlds largest single religious body.

As the worlds largest Christian Church, the Catholic Church currently claims near one-sixth of the worlds populationor over one billion peopleas adherents. Since its debut as a major religious presence in the fourth century, Catholicism has profoundly influenced the history of Western civilization. The churchs mission of ecumenism, or the achievement of worldwide spiritual unity, is largely responsible for the fact that its practitioners have touched nearly every corner of the globe. According to church tradition, by the year 100, the earliest apostles had established forty Christian communities in northern Africa, Asia Minor, Arabia, Greece, and Rome. After Christianitys legalization in 313, Catholicism established major power centers throughout the Byzantine Empire, and in the sixth century, missionaries spread from thence into northern Europe, working among the Germanic, Irish, and Slavic peoples, and eventually reaching the Vikings and other Scandinavians in later centuries.

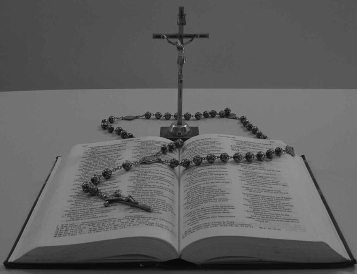

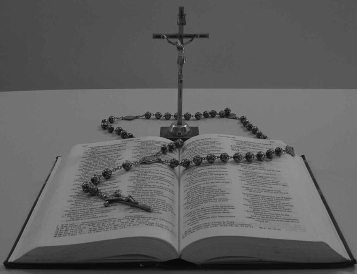

The Bible is sacred to all Christian denominations. The crucifix is a common devotional object in Eastern Orthodox, Catholic, and Episcopalian churches (most Protestant denominations use the cross, without Christs body). The rosary is a traditional form of devotion among Catholics, who use rosary beads like the ones shown here to keep track of their prayers.

The High Middle Ages were marked by contention and warfare as the Christian Church irreparably split in 1054 into Eastern and Western factions over matters of jurisdiction and doctrine, and the Holy Crusades were launched against the Turks. Missionaries resumed their work throughout the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, spreading Catholicism to the Americas, Asia, Africa, and Oceania. Martin Luthers Ninety-Five Theses of 1517, attacking major doctrinal points of Catholicism, led to the Protestant Reformation, which in turn sparked wars in Germany and France, and resulted in the dissolution of monasteries and the confiscation of Catholic churches throughout England, Wales, and Ireland. However, the church would recover from the blow with their Counter-Reformation of the mid-1500s, which reaffirmed many basic Catholic doctrines, improved the education of clergy, consolidated the central jurisdiction of the Roman Curia, and initiated the development of new religious orders, some of which would become highly influential themselvessuch as the Jesuits. In fact, Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier was responsible for the introduction of Christianity to Japan; by the end of the sixteenth century, tens of thousands of Japanese followed Roman Catholicism.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the church focused mainly upon the New World, where Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries were hard at work converting Native Americans. Though Junipero Serra did succeed in establishing missions along the California coast, the introduction of Western civilization to the area on account of these missions resulted in the annihilation of nearly a third of the native population, primarily through disease. New technologies and weaponry developed in the nineteenth century allowed European powers to gain control of most of the African interior. Catholic missionaries were close on the heels of the newly installed colonial governments, building schools, monasteries, and churches.

The twentieth century saw comprehensive doctrinal reforms within the Catholic Church, especially after the Second Vatican Council from 19621965, which, in an attempt to modernize the traditional teachings of Catholicism, made changes to old rites and ceremonies. The public responded in a variety of ways, from ceasing to attend church to gracefully embracing the changes. Some congregations dissented, forming todays Traditionalist and Liberal Catholic groups. The twenty-first century brought church scandal to the attention of the public sphere when several major lawsuits were brought against priests in 2001 for sexual abuse of minors. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops commissioned a nationwide study that found that 4 percent of all priests who served in the United States from 1950 to 2002 faced some sort of sexual accusations. Further criticism of the church ensued when it was discovered that some bishops knew about allegations and, rather than removing the accused, reassigned them. Pope John Paul II responded with the statement, there is no place in the priesthood and religious life for those who would harm the young. In an effort to curb further instances of abuse, the church now requires background checks for church employees and disallows ordination of men with deep-seated homosexual tendencies. The church asserted its concern in 2008 with acknowledgement that the scandal was a very serious problem.

Despite setbacks encountered through the ages, the Catholic Church remains a staunch force in the religious arena, with representatives in almost every country and niche of society. In light of its successful growth and development into the dominating Christian denomination, achievement of its goal of ecumenism, instilled at a time when the Christian minority was persecuted as heathens, must be considered an overall success.

B. The Religion in America

The history of Catholicism in America precedes British colonization; in fact, the first American Catholics were Native American and black slave convertsthe products of Franciscan and Jesuit missionary work. Throughout the sixteenth century, French and Spanish missionarieshailing in ancestry from the Church of Romeserved as the two primary forces of Catholic evangelism in the uncharted territory of the New World. Spanish explorers devoted their colonizing endeavors to the southern and western regions of present-day America, establishing settlements in what are now the states of Florida, Texas, New Mexico, and California. Such settlements became centers of an intense (and often oppressive) effort to Christianize and domesticate the indigenous population inhabiting the land. While a minority of Native Americans did come to adopt a more European way of lifeliving in towns and taking on work as herds-men, carpenters, blacksmiths, or masonsthey did so at the cost of their freedom, for attempts to leave the mission were met with severe corporal punishment. Concurrent with Spanish colonization, French missionaries were making similar efforts with Native Americans living along the banks of the St. Lawrence River in areas that are now Maine and northern New York, and around the Great Lakes and in the Mississippi River valley. Such work at the hands of the French took a great toll on all parties involved, as priests of differing orders often pitted tribes against each other, resulting in large-scale massacres and martyrdom.

Next page