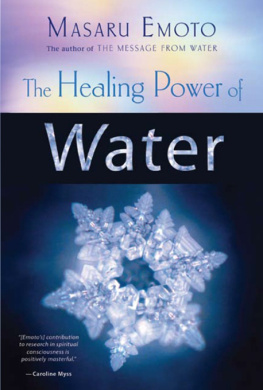

Gonna Trouble the Water

GONNA TROUBLE

THE WATER

Ecojustice, Water, and

Environmental Racism

Edited by

Miguel A. De La Torre

Foreword by

Governer Bill Ritter

The Pilgrim Press

700 Prospect Avenue East

Cleveland, Ohio 441151100

thepilgrimpress.com

2021 Miguel A. De La Torre

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission.

Published 2021.

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

courtesy of the Margaret E. Scheve Archives and Special Collections, Iliff School of Theology, Denver. Photo by Erin Shafer.

republished with permission of InsideClimate News, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that covers energy and climate changeplus the territory in between where law, policy, and public opinion are shaped.

Printed on acid-free paper.

21 22 23 24 25 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020947482

ISBN 978-0-8298-2169-7 (alk . paper)

ISBN 978-0-8298-2171-0 (ebook)

Printed in The United States of America.

to

Nick R.

Contents

Governor Bill Ritter

Miguel A. De La Torre

Miguel A. De La Torre

Loring Abeyta

Jennifer S. Leath

Garam Han

Ved P. Nanda

Michelle Martinez

Rudolph P. Reyes II

Eric C. Smith

Oscar Eduardo de Paz

Foreword

Governor Bill Ritter

When the chapters for this book were presented by the authors at a forum at the Iliff School of Theology, it was my privilege to be present and to be invited to present as well. Although I run a clean energy policy think tank at Colorado State University, I learned much about water on my familys dry land wheat farm, then during my three-year stay in the Western Province of Zambia running a nutrition center, and finally during my time as Colorados governor. With that said, when I observed the presentations, and I read the chapters in this book, I was in awe. I was compelled to consider water, and the many intersections explored here, in ways I never had before.

There is little doubt that water, like blood, is life-giving. And owing to its precious nature, water has become one of many natural resources in our ecology that has been bought and sold, too often not on equitable terms, used as a lever in uneven negotiations, poisoned to the detriment of the marginalized, or just downright stolen. And that is to name only a few of the ways that water has been mismanaged and mistreated. In the most elegant and eloquent of terms, these authors look at the deep and abiding intersections of water with race, with indigenous peoples, with development, with ecology generally, and with a host of other issues as well. And, at every turn, we are required to consider issues of justice generally, and ecological justice specifically.

I believe that most people in America, and throughout much of the globe, care a great deal about justice, about fair and equal treatment. But too often, justice concerns are thought about in overly simplistic termsno one should be the victim of a crime, violent and non-violent alike. No one should be punished for the bad conduct of another. There should recompense if someone defrauds another, or deceives them in a business transaction, or injures them with tortious conduct. In fact, in the United States and around the globe, we have institutionalized a rule of law and a court system for just these reasons. But what happens when we think more deeply about justice, injustice, and the natural world, when we think about natural resources, and perhaps most important among them, when we think about water.

The chapters of this book will answer many of those questions from the perspectives of the respective authors, and there is nothing simplistic about it. Their writings revolve around ecological justice, but at a deeper level they make me weep for indigenous peoples who were stewards of water until it was taken from them, for marginalized communities who were an afterthought where access to clean water was concerned. They make me weep for land that once was fertile and fecundand now sits parched and sterile. My hope is that we will someday live in a world where ecological justice will be not a product of conflict resolution, but at the forefront of every humans mind. These chapters and these authors can help us find our way there.

Introduction

Miguel A. De La Torre

The forty-fifth president of the United States appears to have a distressing and disconcerting obsession with waterspecifically, toilet water. On the eve when the US House of Representatives voted, mainly along party lines, to impeach Donald Trump on two articlesabuse of power and obstruction of Congressthe president spoke at a rally in Battle Creek, Michigan (December 18, 2019), one would have thought he would have professed his innocence or laid out his defense against impeachment. Instead he spent a good portion of his speech waging an ongoing feud against bathroom fixtures with water-conserving features. He was perturbed that bathroom fixtures, specifically toilets, now require ten flushes as opposed to just one. According to the president: Ten times, right? Ten times. [He then made a flushing motion with what appeared to be a flushing sound, bah, bop] Not me of course, not me, but you. You. In Trumps mind, there exist places where there is so much water we simply dont know what to do with it. So on the night of his impeachment, a historical event that has only occurred two other times in this nations history, the president of the United States is telling a rally of supporters that he does not defecate much, but they doso much that it requires ten flushes to finally remove all the manure because of the inefficiency of water-efficient toilets.

While his fevered rant against water conservation might appear humorous if expressed by ones favorite drunk uncle during a family gathering, it becomes life-threatening when spoken by the so-called leader of the free world. His directives to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to adjust its policies in order to deregulate toilets may appear harmless and probably will go nowhere;

According to the EPAs Scientific Advisory Board, a top panel of government-appointed scientists responsible for evaluating the scientific integrity of public policies, President Trumps proposal to rewrite the Obama-era regulation of waterways neglects established science, by failing to acknowledge watershed systems. The forty-one scientists, many of whom were hand-selected by the Trump administration, found no scientific justification for excluding certain bodies of water from protection under the new regulations.

Regardless if some future 46 attempts to undo the damage that 45 wrought, the injury to the nations fragile water systems may well be irreversible. Trump, along with many Euro-Americans, have a misconception concerning water, one where it is reduced to a plentiful commodity exploitable for gain or convenience. Water exists to be used, misused, and abused by those who can profit from its availability. But even those within the dominant culture, those who are more aware of the environmental degradation occurring, still gaze upon water from a position of privilege. Yes, they may be concerned with the sustainability of our planet in general, and water, specifically; nevertheless, their concern is anchored in a Eurocentric worldview that remains irreconcilable with the worldviews emerging from the margins of society. Eurocentric environmentalists mainly profess a commitment to clean air and water or the protection of endangered species. No doubt these are noble and necessary pursuits. But gazing upon water from a position of power and privilege results in a radically different analytical assessment than when conducted from the underside, from the margins, from the perspective of the disenfranchised. If this book had been written by predominately white scholars instead of scholars from or in solidarity with racially and ethnically marginalized communities, the focus on water would have been on the importance of clean water, how we are falling short of this goal, and what actions we can individually or collectively engage which might roll back the devastation being wrought due to neoliberal greed. Again, a worthy discussion in which to engage. But an intention was instead made to gather scholars from or in solidarity with marginalized communities and to gaze upon water through