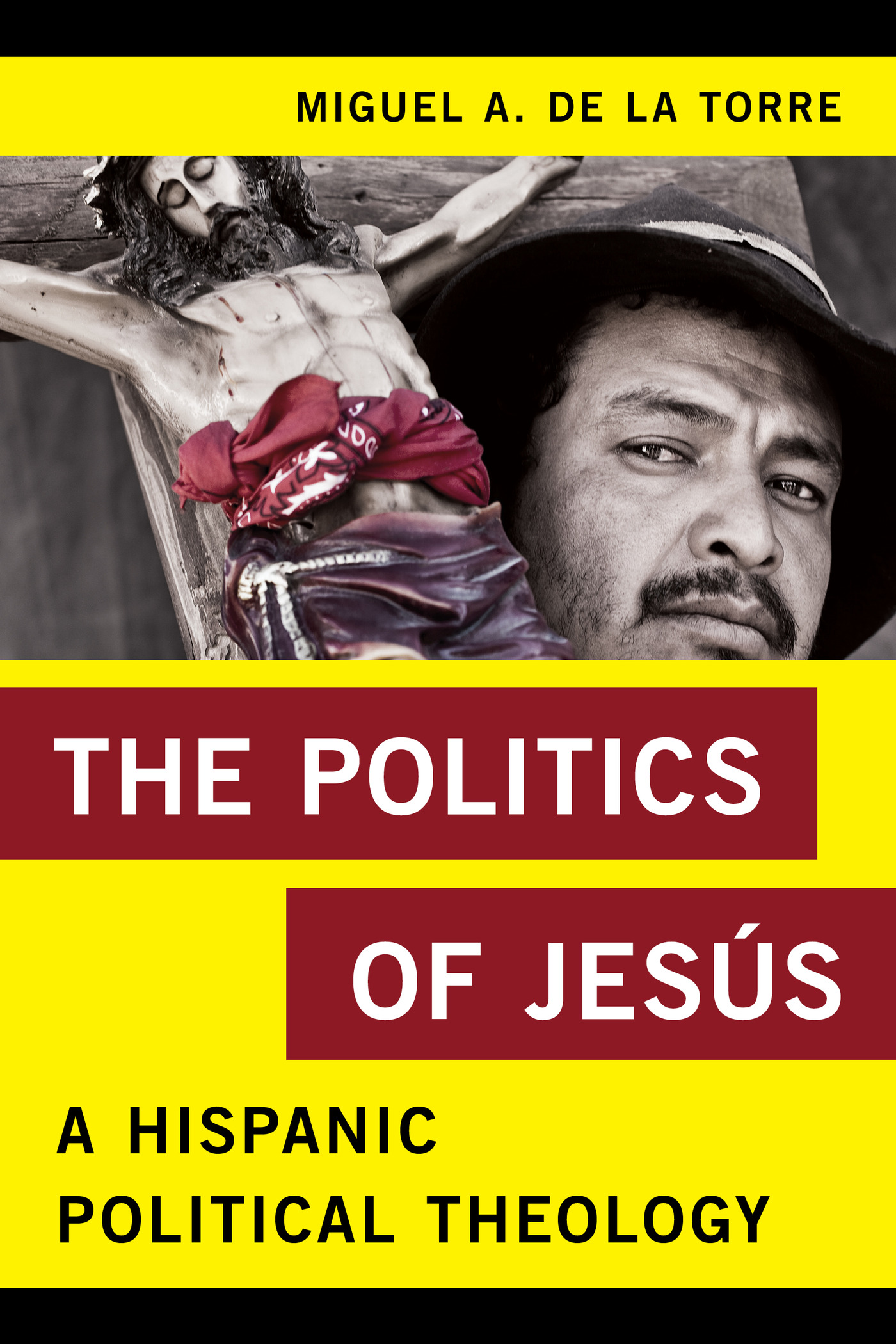

The Politics of Jess

Religion in the Modern World

Series Advisors

Kwok Pui-lan, Episcopal Divinity School

Joerg Rieger, Southern Methodist

University

This series explores how various religious traditions wrestle with the dynamic and changing role of religion in the modern world and examines how past changes reflect on todays critical issues. Accessibly and engagingly written, books in this series will look at secularization, global society, gender, race, class, sexuality and their relation to religious life and religious movements.

Titles in the Series

Not Gods People: Insiders and Outsiders in the Biblical World, by Lawrence M. Wills

The Food and Feasts of Jesus: The Original Mediterranean Diet, with Menus and Recipes, by Douglas E. Neel and Joel A. Pugh

Occupy Religion: Theology of the Multitude, by Joerg Rieger and Kwok Pui-lan

The Politics of Jess

A Hispanic Political Theology

Miguel A. De La Torre

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2015 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

De La Torre, Miguel A.

The politics of Jess : a hispanic political theology / Miguel A. De La Torre.

pages cm. (Religion in the modern world)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4422-5035-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4422-5036-9 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4422-5037-6 (electronic)

1. Jesus ChristHispanic American interpretations. 2. Liberation theology. 3. Marginality, SocialReligious aspectsChristianity. I. Title.

BT304.918.D4 2015

232.089'68073dc23

2015017834

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

To: The Ethicists Responsible for my

Early Formation

Glenn Stassen, my first ethics professor who stressed the importance of faith

John Raines, the chair of my dissertation committee who introduced me to the intersection of postmodern and postcolonial thought with ethics

Katie Cannon, dissertation member who expanded my understanding of liberationist ethical thought to include those on my margins

Allen Verhey, who pushed a reluctant institution to hire me at my first teaching post

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to the honor students and faculty of the Religion Department at the University of Johannesburg in South Africa. During the fall of 2014, they invited me to be a visiting professor and provided a comfortable house where I could write. While there, I wrote the bulk of this book. Free from distractions, I had time to think deeply about who and what Jesus is to the Hispanic community and to me personally. The hospitality shown to me while in South Africa made this book possible. A special thanks is offered to the department chair, Farid Esack, and faculty members Lily Nortje-Meyer, Hennie Viviers, Shahid Mathee, and Maria Fraham-Arp. They gave generously of their time, taking me to different parts of the city and teaching me what it meant to live in the new South Africa. They proved to be excellent conversation partners, providing valuable feedback after reading early rough drafts of this manuscript. I am also grateful to the AbuBakr Karolia family for opening their home to me, and to Maurice Jacquesson, Mohamed Ismael, and K. Ashraf, who were kind enough to spend much time showing me around the country.

This trip was also made possible thanks to the Iliff School of Theology, who provided me with the funds to travel and the release time to teach abroad. Specifically, I want to thank the president, Thomas V. Wolfe, and the dean of academic affairs, Albert Hernndez for their vision to make Iliff a truly international institution. And finally, I need to thank my family, especially my wife from whom I was separated for several months while I was teaching abroad. I am deeply grateful for her belief in the work I do.

Foreword

In 1992 I dissolved my thirteen-year-old real estate company and moved to Louisville, Kentucky, to begin a seminary education at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. An avowed capitalist, a conservative Christian, and an activist in rightwing Republican politics in Miami (who ran in 1988 for the Florida House of Representatives), I now wanted to become a pastor, hoping to make a difference in the world for the cause of Jesus Christ. I wanted to embody the Good News of Jesus within society by making a political move toward what I, at the time, defined as a fairer and more equitable society. In short, I wanted to claim the United States for Jesus! While at Southern, I took the required ethics class that was then taught by Glen Stassen. Prior to entering his classroom, I erroneously equated ethics with a review of a pastoral code of behavior focused on personal piety; a dos and donts list for future ministers. If Im honest, I was not looking forward to such a discussion, but it was, after all, required for graduation. To my pleasant surprise, the class Stassen taught instead challenged me to think deeper on the role of humans, specifically Christians, within society. What is our responsibility, our duty, as people of faith, to the culture in which we live?

During my studies, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary was in turmoil. When I graduated in 1995, the fundamentalists, under the leadership of incoming president Al Mohler, literally took over the power structures of the seminary. Ironically, as the seminary moved to the conservative far right, I started tilting toward the far left, becoming at the end, a self-identifying liberation theologian. My conversion occurred in the school library, long after all my class assignments were completed, reading the works of South American liberation theologians that were never assigned in class. The takeover of the seminary (which I first supported, only to deeply regret said support as my consciousness was raised by the time I graduated) became a hostile environment for professors who made students think beyond simplistic answers and supposed doctrinal truths. They were either purged or they voluntarily left before the inevitable. Not surprisingly, Stassen was among the first to leave Southern. As for myself, unable to find a pastoral assignment within a rightward moving denominational milieu, I did what any unemployed college student does: I pursued my PhD.

Years passed, I obtain my doctoral at Temple University under the tutelage of ethicists Katie Cannon and John Raines and started teaching social ethics at Hope College in Holland, Michigan, thanks mainly to ethicist Allen Verhey. It wasnt long before Stassen and I reconnected at the Society of Christian Ethics. He honored me by offering an invitation to teach a summer course in 2003 at Fuller Theological Seminary. During this time, I had the opportunity to get to know him better. One sunny California day, while walking through Fullers campus, Stassen rode up on his bike. He stopped and we began an impromptu conversation on the concept of needing a thicker Jesus, a theme that he was at the time developing. He was concerned that the discourse of ethics used a Jesus that was way too thin and anemic for his liking. He argued that Jesus is thickened when the faithful move beyond compartmentalizing Jesus, relegating him to religious rituals and events and, instead, make him Lord over every aspect of their life. Only then can one participate in what he called incarnated discipleship as modeled by individuals like Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Martin Luther King Jr.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.