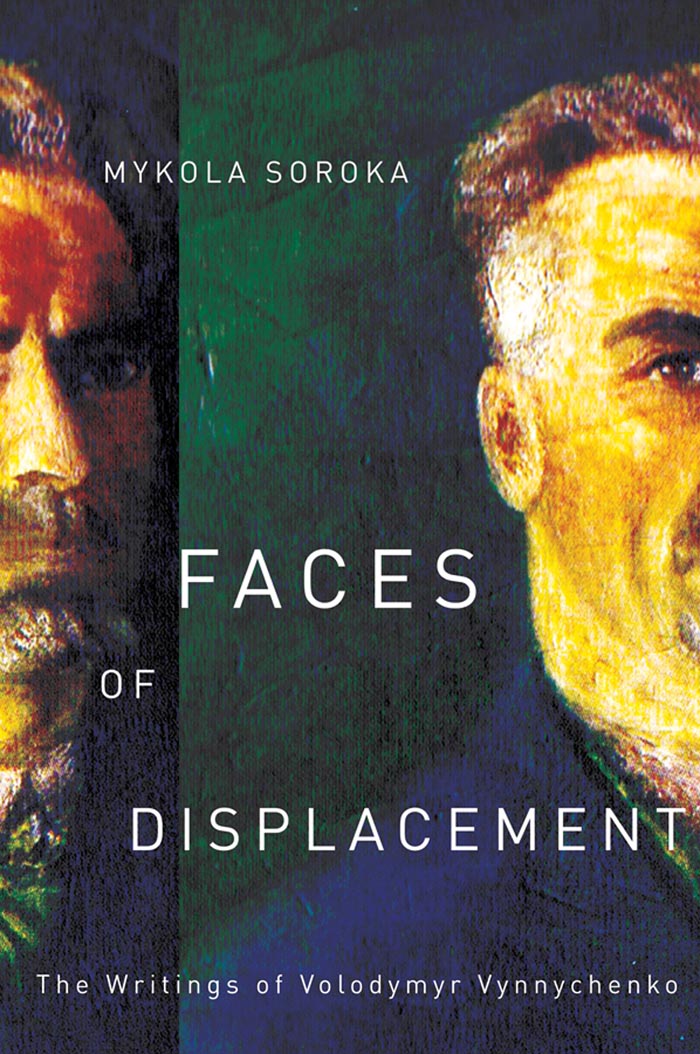

FACES OF DISPLACEMENT

Faces of Displacement

The Writings of Volodymyr Vynnychenko

MYKOLA SOROKA

McGill-Queens University Press

Montreal & Kingston London Ithaca

McGill-Queens University Press 2012

ISBN 978-0-7735-4037-8

Legal deposit third quarter 2012

Bibliothque nationale du Qubec

Printed in Canada on acid-free paper that is 100% ancient forest free (100% post-consumer recycled), processed chlorine free

This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Aid to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Funding has also been received from the Canadian Foundation for Ukrainian Studies.

McGill-Queens University Press acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Soroka, Mykola

Faces of displacement : the writings of Volodymyr Vynnychenko / Mykola Soroka.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7735-4037-8

1. Vynnychenko, Volodymyr Kyrylovych, 18801951 Criticism and interpretation. 2. Vynnychenko, Volodymyr Kyrylovych, 18801951 Exile. 3. Vynnychenko, Volodymyr Kyrylovych, 18801951 Travel. 4. Exile (Punishment) in literature. 5. Emigration and immigration in literature. 6. Travel in literature. 7. Identity (Philosophical concept) in literature. 8. Politics in literature. 9. Ukraine In literature. I. Title.

PG3948.V88Z87 2012 891.7933 C2012-903751-6

Typeset by Jay Tee Graphics Ltd. in 11/13.5 Garamond Premier Pro

For Nadiya, Rostyslav, and Lubomyr

Contents

Acknowledgments

Many nice people have been involved in the creation of this book by making valuable comments, sharing interesting ideas, and inspiring the author with a creative zeal. Here I would like to express my deepest gratitude to all of them.

George Grabowicz was the first who supported my endeavour during my Fulbright stay at Harvard University, where I became interested in issues of displacement. The main idea of the project was crystallized during my PhD program at the University of Alberta, and here my especial thanks go to Oleh Ilnytzkyj and Natalia Pylypiuk for their great mastery of supervision and enormous efforts to shape and stimulate my thoughts, which constitute the core of this work, as well as for their human responsiveness and understanding. Further steps were made during my postdoctoral program at the University of Toronto, where Maxim Tarnawsky encouraged me, with his indefatigable optimism, to complete the project and helped in finalizing the structure of the book. Finally, the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Alberta, with its inspiring atmosphere and traditions of high academic standards, has become an ideal place to make the last touch, and I am greatly indebted to its director Zenon Kohut, assistant director Bohdan Klid, and all my colleagues.

I also extend my deepest thanks to all those whose critical observations and useful suggestions helped me in various ways to keep on the right track and finish the study: Paul Hjartarson, Bohdan Nebesio, John-Paul Himka, Myroslav Shkandrij, George Mihaychuk, Larysa Onyshkevych, Olga Andriewsky, Volodymyr Panchenko, Ksenya Kiebuzinski, Jars Balan, Janice Kulyk Keefer, Walter Smyrniw, and Valentyna Kharkhun.

Let me express my highest respect to the two oldest members of our scholarly community, the late professors Valerian Revutsky and Michael Kalinowski. The former, an eyewitness to Vynnychenkos popularity in 1920s Ukraine, gladly provided me with copies of the writers rare publications. The latter shared his personal impressions about his meeting with Vynnychenko in postwar France. Alain Mothu, an owner of the former Vynnychenko estate in Mougins, appeared to be a very kind man who allowed me to explore this historical site and shared his knowledge of the writers legacy.

I am also grateful to Olena Jennings, Marta Olynyk, Marta Baziuk, and Lida Somchynsky for their assistance with harnessing the language, translations, and timely editing.

I am thankful to two institutions: the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies whose award, the Helen Darcovich Memorial Doctoral Fellowship, enabled me to complete my doctoral program, and the Shevchenko Scientific Society in the usa, whose grant helped to work on the project.

Let me also acknowledge the cooperation of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the usa (president Albert Kipa) for granting permission to use photos, as well as Slavonic and East European Review and Canadian Slavonic Papers for allowing to include modified parts of this study which were previously published in these journals.

Final words of gratitude go to my family: my wife Nadiya for her invaluable moral support, titanic patience, and technical assistance, and my sons: Rostyslav, for letting me use the computer when he was not playing computer games, and Lubomyr, who was born during the course of this work and became a great inspiration.

Preface

The objective of this study is twofold: to contribute to the contemporary theoretical discussion about literature and the experience of displaced writers abroad, and from this largely neglected perspective to present a case study of the writings of the Ukrainian writer Volodymyr Vynnychenko (18801951). When I started the project, I confronted a methodological dilemma. I had to decide whether to focus on a more established concept, such as that of the exile, or migr, or emigration, or focus on more recent notions such as the diaspora, nomadism, or travel. My initial intention was to follow the beaten path and work within the traditional framework of exile studies. Nonetheless, upon starting the project I became confused by the debates among literary critics who tried to defend the priority of their point of view in how this concept of exile was applied. For instance, Hallvard Dahlie classifies the British writer of American extraction Henry James as an exile (5). However, Terry Eagleton sees both James and Polish-born novelist Joseph Conrad as emigrants who chose English society from the outside and did not want to return (14). At the same time, a broader study of Conrad suggests that he can also be regarded as an exile, and his works can be seen as an attempt to transcend the bitterness which resulted from his experiences as an exile (Gurko, Milbauer). Moreover, some have even argued that Conrad, who is usually understood as a British writer, can actually be viewed as a Polish writer (Mleczko in Morf, 234). In going through this terminological and conceptual jungle, I realized that any one framework, though it might be useful for addressing specific issues, would nevertheless place excessive restrictions on my research methodology and impede the formulation of broader perspectives on the Ukrainian writer Vynnychenko.

discourse, or an uprooted nomad whose love of homeland extends to embrace the whole planet.

As a case study of displacement, I find the figure of Vynnychenko to be extremely fitting. The fact that this writer lived most of his life and wrote the majority of his works outside his homeland (he spent about thirty-one years in Ukraine and forty abroad) has remained largely unnoticed and barely conceptualized. Given Vynnychenkos status as one of the most renowned and influential writers in Ukrainian literature, analysis of work has been conducted for the most part in the mainstream discourse, which often ignores tangential discourses. This phenomenon of marginalization is quite apparent in the study of Ukrainian diasporic literature. In Soviet literary criticism, the principle of Antaeus was applied: i.e., literature written abroad cannot be true literature because it is detached from the native social and cultural milieu (Soroka 2000). Yevhen Shabliovsky, for example, substantiates his criticism of Vynnychenko as follows: Taking Vynnychenko as an example, we are again persuaded that an artist who gives up his progressive principles and betrays his people cannot create anything considerable and significant, and he becomes like a sterile flower (48). This approach was largely motivated by Soviet ideological prejudice toward so-called Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists. At the same time, a colonial approach was also at work: whereas Russian migr anti-Communist writers (e.g., Ivan Bunin) were published in the USSR, the works of Vynnychenko a former member of the Social-Democratic and Communist parties and insistent supporter of leftist ideals were falsely lambasted as bourgeois nationalist (Shabliovsky).certain circles in the diaspora considered Vynnychenko to be too left-leaning and modernistic. They refused to support the almanac