The Choctaw before Removal

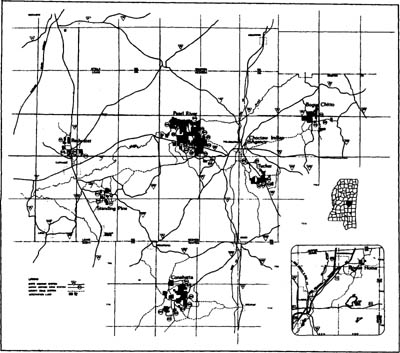

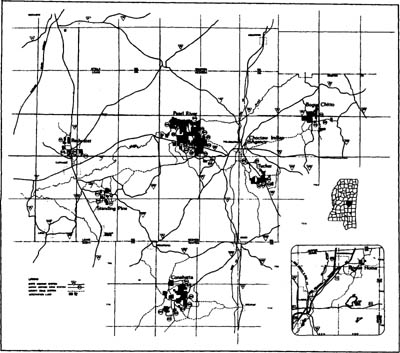

Choctaw Indian Communities, 1984.

Source: U. S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs

The CHOCTAW before REMOVAL

Edited by

Carolyn Keller Reeves

Copyright 1985 by the University Press of Mississippi

and Choctaw Heritage Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Print-on-Demand Edition

This book has been sponsored by the Choctaw Heritage

Press, Philadelphia, Mississippi, and has been partially

funded by the U.S. Department of Education, Office of

Indian Programs. The opinions expressed herein do not

necessarily represent the views of the U. S. Department

of Education, Indian Education Program, Title IV,

Part B.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Available

ISBN 1-57806-685-9

Tribal Credits

Tribal Chief

Phillip Martin

Chairperson, Education Committee

Luke Jimmie

Director,

Choctaw Department of Education

Carolyn Collins

Director,

Research and Curriculum Development

William Brescia, Jr.

Advisory Committee,

Research and Curriculum Development

Terry Ben, Bob Ferguson, Patricia K. Galloway,

Eddie Gibson, Kevin Grant, Sharron Cauthen,

and Wanda Kittrell

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to the following people: to Ken York, who has assisted my study of the Choctaw language; to Abbie Gibson Phillips, who taught me to speak, read, and write the Choctaw language; to Phillip Martin and Calvin Isaac, both of whom served terms as tribal chief during my work with the Choctaw bilingual education project; to linguists Nora England, Pat Kwachka, Alvin Cearley, and Loren Nussbaum, who encouraged my study of the Choctaw language; to Bill Brescia, for his critique of my editing; to Tom Pickering, Gary Rush, and Bobby Anderson, for their support at the university; to my friends and colleagues at the University Reading Center and in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction, for their support and encouragement; to Marie Mills, Ann Ulmer, and Dana Thames, who typed the essays into the word processor; and to Beth and Mark Richmond, Richard Kazelskis, and my daughter, Rhea Ann, for their love and emotional support. I thank all of these people for their many kindnesses to me.

Chahta A h a ya Moma

The phrase literally means Many Choctaw Standing; in Choctaw the phrase suggests Choctaw endurance. Surely the Choctaw will endure.

INTRODUCTION

Who Speaks for the Choctaw?

Carolyn Keller Reeves and Samuel J. Wells

Although the longitudinal impact upon the Choctaw and other Native American groups of European settlement has been documented, no book-length analysis describes the anthropological condition of the Choctaw as well as the relationships among the combined forces which eroded the cultural, economical, and political foundations of the Choctaw prior to their removal to Oklahoma. Nor, in spite of their role as central characters in Mississippi history, is there a chronological presentation of significant experiences encountered by the Choctaw prior to removal. Histories have not focused on the Choctaw. Furthermore no available study combines cultural anthropology with history to examine the basis for Choctaw endurance, the progressive changes which occurred within the Choctaw culture as their interaction with diverse groups of people became more intense, and the reasons why the Choctaw succumbed to removal.

Previous books, such as Horatio B. Cushmans History of the Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Natchez Indians (Stillwater, Okla.: Redlands Press, 1962) and Indians of the Southeast: Then and Now (New York: Abingdon Press, 1973), by Jesse Burt and Robert B. Ferguson, have dealt with the Choctaw in relation to the history of the Southeastern tribes but have not emphasized the culture and history of the Choctaw as a separate entity. Although Cushmans book provides an excellent record of his personal interactions with the Choctaw, along with his observations concerning their cultural beliefs and a great deal of information about various treaties with the United States, the arrangement of the content is somewhat haphazard, making it difficult to obtain a global, chronological view of Choctaw history.

Studies focusing on the Choctaw are available. Angie Debos Rise and Fall of the Choctaw Republic (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1934) is an excellent study; however, it primarily covers the history of the Oklahoma Choctaw after the American Civil War, addressing specifically their social and economic readjustments. Authur H. DeRosiers The Removal of the Choctaw Indians (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970) is a stimulating discussion and assessment of the major events, personalities, and issues surrounding Choctaw removal, but in-depth coverage is restricted to the interactions of the Choctaw with the federal government during the 1800s. Debos and DeRosiers works are valuable because the information they contain comes from excellent primary sources supplemented by the best of the secondary sources. A more recent book by Jesse O. McKee and Jon A. Schlenker, The Choctaws: Cultural Evolution of a Native American Tribe Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1980), focuses on Choctaw land cessions and acquisitions and their way of life after removal but with less than fifty pages on the condition of the Choctaw before the 1800s, a comprehensive view of their cultural evolution is not provided. While each of these books may be appreciated for the information it does contain, none provides a global view of early Choctaw ideology together with an interpretation of the ways in which Choctaw ideology was effected by European groups, frontiersmen, and state and federal officials, all of whom were vying for land and power within the New World from 1540 to 1830.

In order to appreciate fully the manner in which the Choctaw were able to endure the increasing adversity, hardship, and stress thrust upon them prior to 1830, we must understand the ideological framework which governed their behavior before European contact. The present book focuses on three broad areas: Choctaw anthropology, Choctaw beliefs, and the Choctaw experience with the United States government prior to removal.

The essays collected here provide a topical view of the Choctaw tribe for the period 1540 through 1830. Because the authors have diverse interests, some of the essays parallel each other in interpretation, while others offer differing views. For example, Grayson Noley and Patricia K. Galloway disagree as to which Indian groups were allies of the French and English; John D. W. Guice and Samuel J. Wells express similar views of the major factors underlying the formation of federal Indian policy because they address adjacent, overlapping periods of history. Scholarship depends on differing interpretations of events, as well as on consensus, to advance our understanding of history.

The present book contains topics heretofore neglected or studied only in a cursory way. Little attention has been paid, for example, to the place of oral tradition in history, to the Choctaw language, to the Choctaw as economic providers, and to the Choctaw civil war. Some of the topics deserve more extensive treatment than is possible here. Each essay illustrates its argument selectively; it would obviously not have been feasible to include all events and personalities associated with every specific time period discussed.

Next page