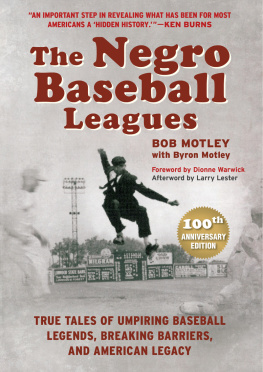

Also by LARRY LESTER

Baseballs First Colored World Series:

The 1924 Meeting of the Hilldale Giants and Kansas City Monarchs

(McFarland, 2006; softcover 2014)

Rube Foster in His Time:

On the Field and in the Papers with Black Baseballs Greatest Visionary

(McFarland, 2012)

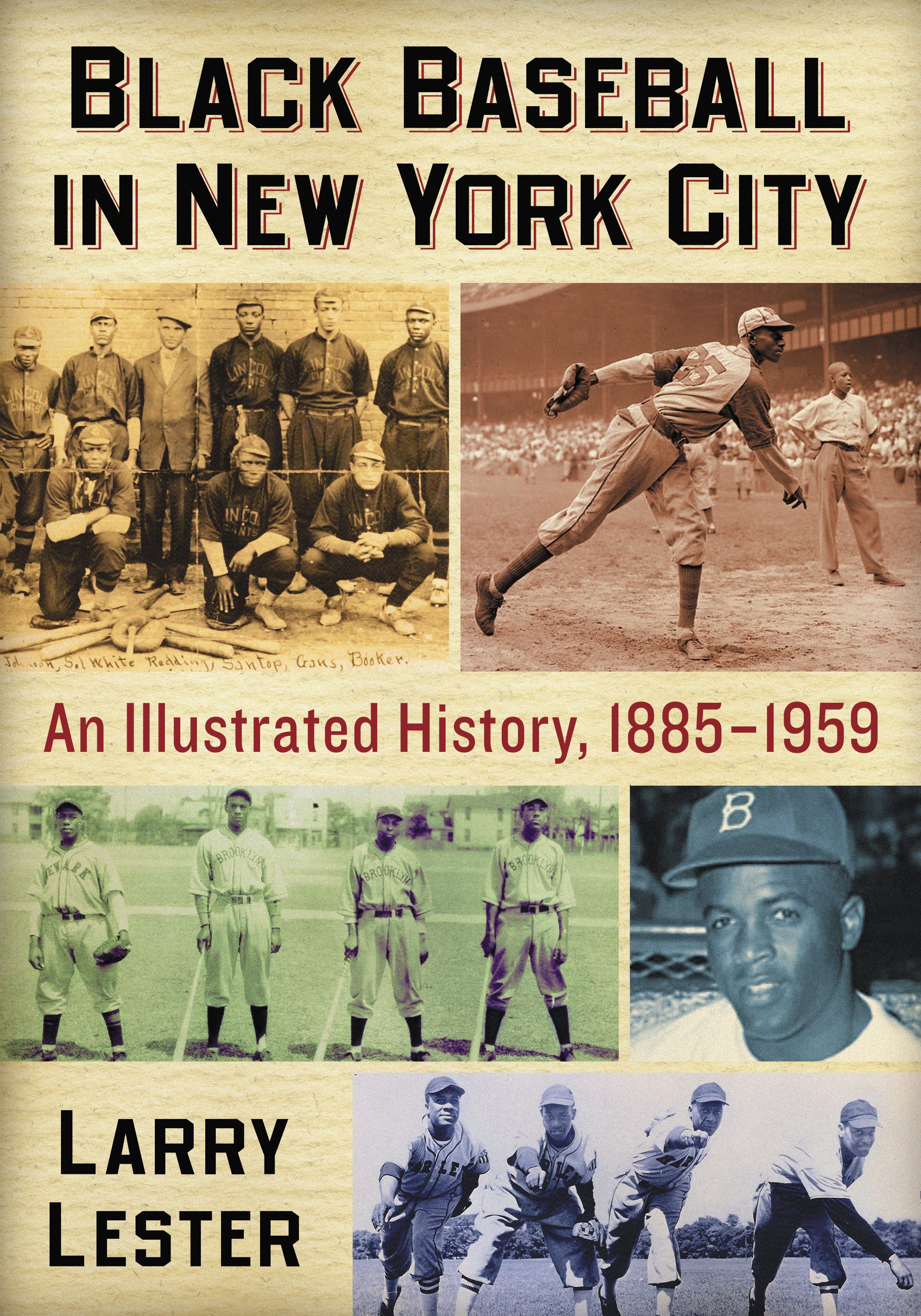

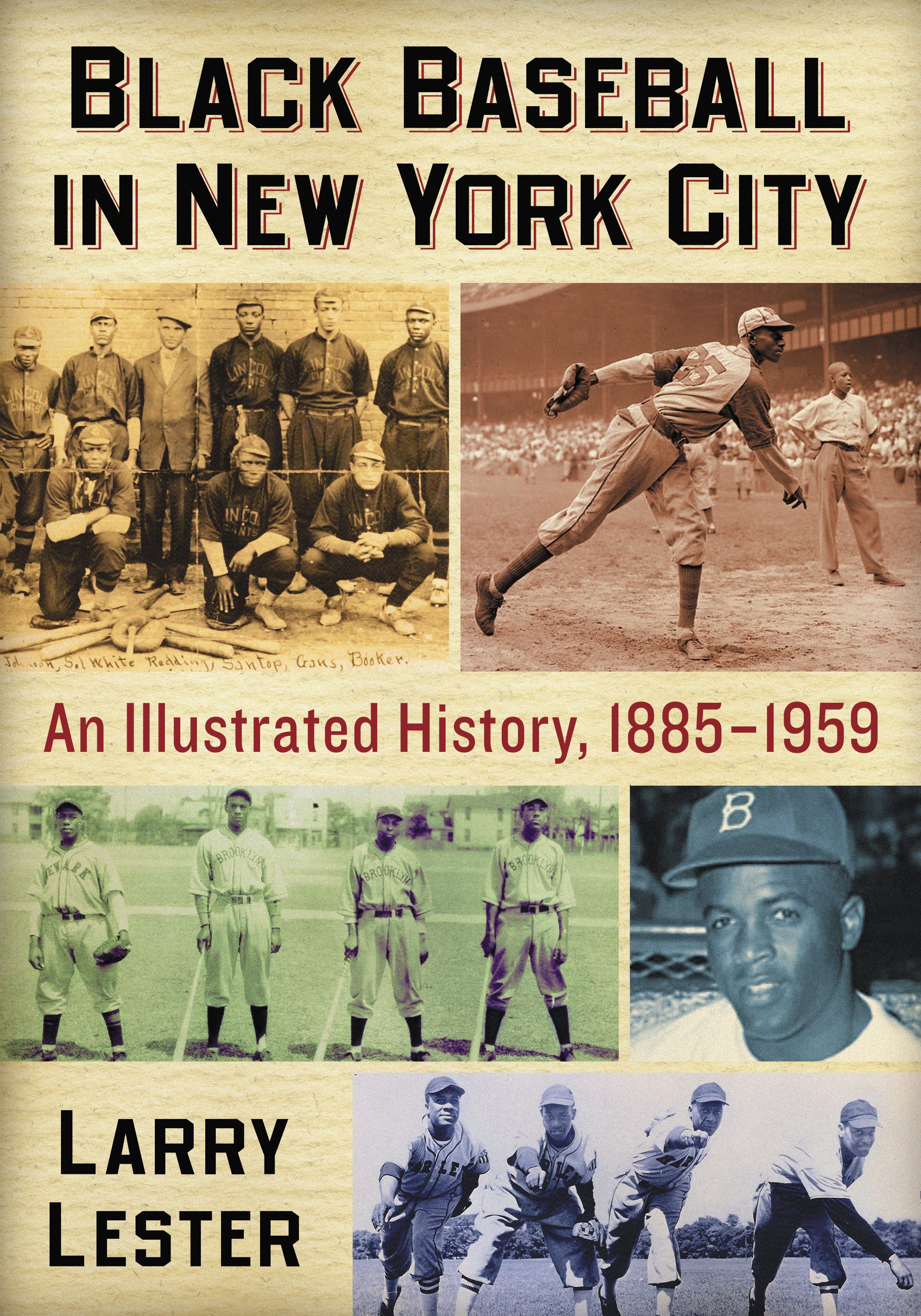

Black Baseball in New York City

An Illustrated History, 18851959

LARRY LESTER

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

Except where otherwise credited,

all photographs are courtesy NoirTech Research.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2941-4

2017 Larry Lester. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover: (clockwise, from top left) 1911 Lincoln Giants, Leroy Satchel Paige in Yankee Stadium, Jackie Robinson of the Brooklyn Dodgers, 1948 Harlem Globetrotters pitching staff, and members of the newly merged Newark Dodgers and Brooklyn Eagles

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To Dunkin Daniel Richison,

my basketball court mentor,

and to the memory of Woody Smallwood (19331995),

a family friend and a mentor for the ages

Woody Smallwood

New York baseball is really all right,

But youd be sadly mistaken if you thought it was all white.

There were players of color all around,

The City that gave the fans a thrill,

By playing baseball at a high level,

Like life up on Sugar Hill

editor Philip Ross, author and historian,

Jamaica, New York

Acknowledgment

After a week of unseasonably warm and sunny January weather, there was a sudden drop in temperature. That Friday morning, January 26, was cold, foggy, damp and rainy. The sun failed to appear that day and so did a gentleman named Dewitt Mark Woody Smallwood.

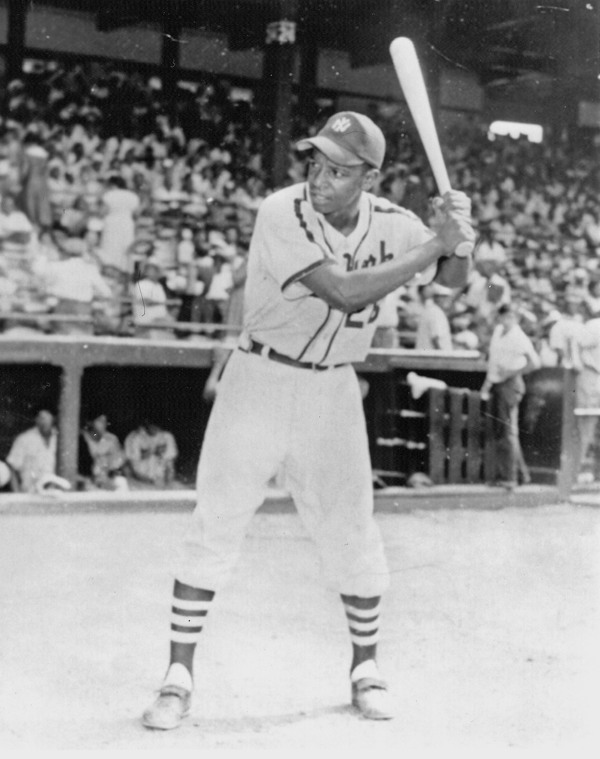

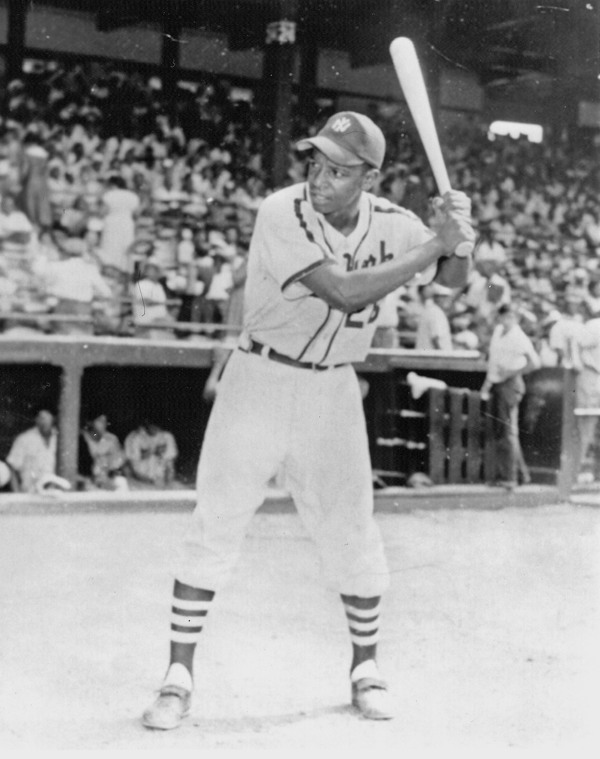

A native of Newburgh, New York, Smallwood grew up in White Plains, New Rochelle and Buffalo. In high school, he played football and basketball, but baseball was his true love. In 1952, he was signed by Albert Buster Haywood to an Indianapolis Clowns contract. Smallwood joined a talented Clowns team that included future home run king Hank Aaron. Woody often recalled how Aaron could make that tin fence in Winston-Salem talk with his line drive hits. Smallwood also enjoyed playing alongside all stars Jim Fireball Cohen and Henry Speed Merchant, and Negro League batting champions Len Pigg and Ray Neil.

That season with the Clowns, according to Howe News Bureau, the leagues official record-keeper during the 1950s, he hit an even .300. Interviews with teammates often testified that Smallwood had the speed of Rickey Henderson, a gold glove like Ken Griffey, Jr., and Rod Carews bat control. Many say he was blessed with insane bolting speed, a quick bat and lots of baseball savvy.

The next year, Smallwood joined St. Jean (Quebec), a Pittsburgh Pirates farm team, while Aaron played in Eau Claire (Wisconsin). Mr. Woody returned to the Negro Leagues in 1954 to play with the New York Black Yankees, Birmingham Black Barons and the Philadelphia Stars. When Branch Rickey signed him to a St. Jean contract, Woody humanized the barrier breaking legend by recalling how Rickeys suit lapels always had cigar ashes on them.

Later in the early 1990s, Woody Smallwood became the Negro Leagues Baseball Museums first president and led a small group of dreamers to a large professional contingent of believers. Under his leadership the Museum reached unprecedented levels of awareness. At many board meetings he would remind us, People, we are now in the big leagues.

As a Special Project Coordinator executive for the High Life Sales Division of the Miller Brewing Company and a former player, Smallwood dedicated his ambitions to building a memorial to the veterans of black baseball. Woody would gladly appear with his gold-headed walking cane and super-shined Stacy Adams footwear, campaigning for corporate funds, speaking at schools, churches, and community organizations on behalf of the NLBM.

A wise man, in dire situations he would often remind us, I know what time it is. In the heat of battle, he encouraged me to reach higher plateaus, saying, Larry, you cant fight, unless you are in the ring. Smallwood always had time to listen to concerns from board members and to make tough decisions in critical situations. He could render presidential decisions from his corporate office, the Museums office, or from his hangout, the Madden Shine Parlor, where home-spun wisdom was at a premium.

Woody Smallwood was always a professional, on and off the field. He always started each board meeting on time and with a prayer. Woody ran his meetings with diplomacy and tact. And when appropriate, to emphasize a point, he would drop to a baritone voice like James Earl Jones. Meanwhile, his Billy Dee Williams smile would dilute any anxiety in the room. Even the eloquent John Buck ONeil would look for his marching orders from President Smallwood.

His earthly time has passed, but he is not forgotten. The Museum that he helped birth will be eternally grateful for the time he delightfully shared. For he knew what time it really was!

In Smallwoods home going celebration, his wife Barbara expressed, I love you, Dewitt, and Ill carry your love in my heart every day, for strength, guidance and courage. It fills me with pride and joy to have had you as my husband.

Preface

New York City, New Jack City and Sugar Hill are names synonymous with life in the city that never sleeps. Sugar Hill was likely named for the sweet life its affluent residents enjoyed during black baseballs heyday during the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. Roughly bounded by West 155th Street to the north, West 145th Street to the south, Edgecombe Avenue to the east, and Amsterdam Avenue to the west, in Upper Manhattan and known for its distinguished and magnificent row houses and elegant apartments, Sugar Hill is more a state of mind than an actual geographic location.

In the March 27, 1944, edition of The New Republic, Langston Hughes wrote about the cultural richness of the neighborhood in his essay Down Under in Harlem.

If you are white and are reading this vignette, dont take it for granted that all Harlem is a slum. It isnt. There are big apartment houses up on the hill, Sugar Hill, and up by City Collegenice high-rent-houses with elevators and doormen, where [actor] Canada Lee lives, and [Blues musician] W. C. Handy, and the [journalist] George S. Schuylers, and the [civil rights activist] Walter Whites, where colored families send their babies to private kindergartens and their youngsters to [the private] Ethical Culture [Fieldston] School.

Harlem in general, and the Sugar Hill district in particular, was never a slum to renowned painter Aaron Douglas, scholar W. E. B. DuBois, future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, politician Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., and singer/actor Paul Robeson, nor to musicians like Count Basie, Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, and rock n roll idol Frankie Lymon, along with athletes like pugilist Joe Louis and Say Hey Willie Mays.

Next page