Contents

2017 by Robert F. Garratt

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Garratt, Robert F., author.

Title: Home team: the turbulent history of the San

Francisco Giants / Robert F. Garratt.

Description: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, [2017] |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016031549

ISBN 9780803286832 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 9781496214072 (paper: alk. paper)

ISBN 9781496201232 (epub)

ISBN 9781496201249 (mobi)

ISBN 9781496201256 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : San Francisco Giants (Baseball team)

History.| BaseballCaliforniaSan FranciscoHistory.

| New York Giants (Baseball team)History. | Baseball

New York (State)New YorkHistory.

Classification: LCC GV 875.s34 g27 2017 | DDC

796.357/640979461dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016031549

Set in Minion by John Klopping.

For my grandchildren:

Leighton Mae, Hudson, and Aidan;

Madeline and Sofia;

Elliott and Olivia.

Touch all the bases

and be safe at home!

ILLUSTRATIONS

Following

GRAPHS

PREFACE

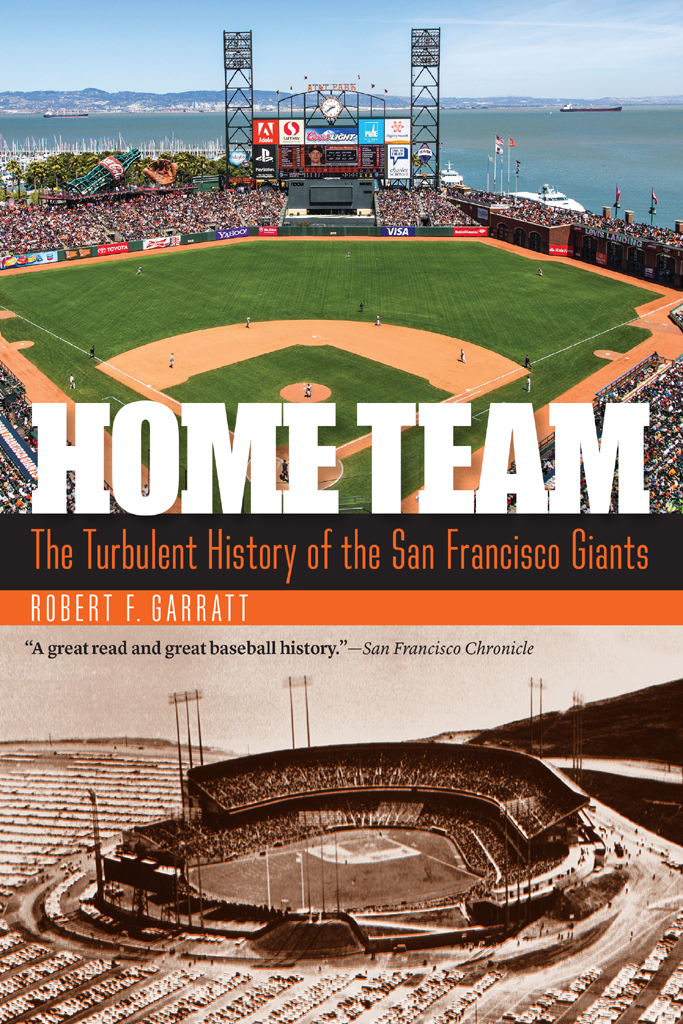

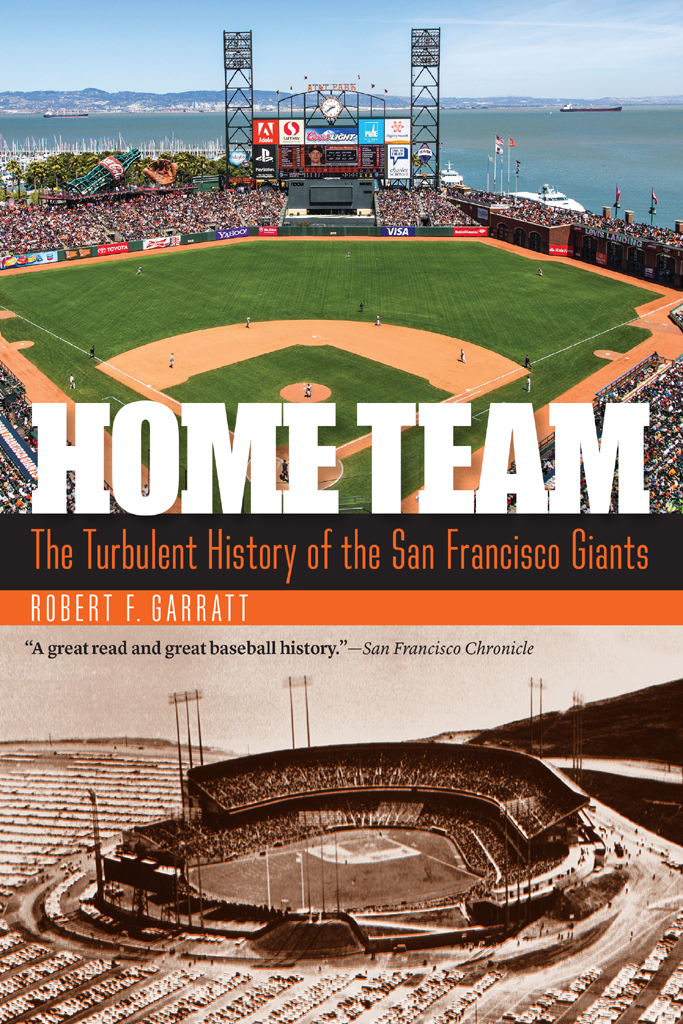

The Giants move from New York to San Francisco has been long overshadowed by an emphasis on the Dodgers and their colorful owner, Walter OMalley, who masterminded his teams move from Brooklyn to Los Angeles the same year that the Giants came west. This book widens the focus on West Coast baseball to treat the story of the Giants move in its own right, rather than as a footnote to the Dodgers story. It also looks at the development of the Giants as a San Francisco team, forging its own history.

The Giants coming to San Francisco involved more than a change in location and an assumption of a new name; it also involved the cultivation of another identity, an important theme in their California story. For all the joy at the beginning of the move, this transition for the Giants was far from easy. Once they settled into their new home and the initial enthusiasm of the relocation had worn off, difficulties arose. After early successes with near misses at league pennants and a World Series championship, there were troubled times, both on the field and at the box office, when attendance slumped so badly that the team almost left town, not once but twice. These periods of ups and downs over the years were indicative of a team struggling with its connection to the city. The story concludes happily, however. The ball clubs fortunes improved dramatically with a move to a new baseball park at the turn of the century; the Giants grew into a stable franchise and became an integral part of the citys cultural life.

This version of the Giants story develops in the form of a biography, not of a human subject but of a team, following a traditional biographical pattern with emphases on the phases of a life: beginnings, with early growing pains; then adolescent-like problems; then adulthood, with certain mid-life crises; and, finally, ending with maturity, an established and comfortable identity. The focus is chiefly on owners, managing partners, team administrators and officials, city politicians, journalists, and individuals behind the scenes, in the background of the game itself, who played an important role, not only in bringing the team from New York to California but also in keeping the team in San Francisco when it appeared that certain conditions might drive the ball club away. These people were part of the business of baseball in the city, running the ball club, coordinating events related to baseball and, especially, dealing with the important and difficult issues about where the team will play and in cultivating the teams relations with the community.

Most of the contemporary writing on the Giants concentrates on their time in AT&T Park, where they won world championships in 2010, 2012, and 2014 and have drawn fans at an extraordinary rate. According to national journals such as Forbes and business websites such as bizjournals.com, the Giants rank in the top five Major League Baseball franchises for profitability, team worth, success on the field, and overall stability. A good example of that stability can be seen in the smooth succession of recent corporate management. When Peter Magowan retired in 2008, Bill Neukom became chief managing partner; and then in 2012, when Neukom left, Larry Baer became the chief executive of the franchise. During this period of change, the ball club has remained not just efficient and secure but also phenomenally successful.

While all of the attention given to the recent success is both relevant and appropriate to the story of the Giants in San Francisco, it is not the primary focus here. This story goes back to the beginning of the move west, to feature both the Giants early years in a new city and their gradual development there over four or five decades, in both rough times and smooth, the years that serve as the bedrock for the ball clubs recent achievements and triumphs, both on the balance sheet and the field of play.

HORACE

In late October of 1954, Horace Stoneham, longtime owner of the New York Giants, was on top of the baseball world and, more important to Stoneham at least, his team was finally the toast of the town, eclipsing both the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Yankees. The Giants had just swept the mighty Cleveland Indians to win the World Series. The Indians, winners of 111 games that year, were heavy favorites, bolstered by a formidable pitching staff with twenty-game winners Early Wynn and Bob Lemon and a great offense anchored by American League batting champion Bobby Avila and power hitters Larry Doby and Al Rosen. But the Giants felt the magic and shocked the baseball world. The Series turned on Willie Mayss famous over-the-shoulder catch in game one, and the Giants never looked back. Defense, speed, timely hitting, and an uncanny knack for substitution in manager Leo Durochers use of pinch hitter Dusty Rhodes were all too much for Cleveland.

The future seemed bright indeed, and thoughts of returning the Giants to their preWorld War II eminence in the National League danced in Stonehams head. He had a young superstar in Mays, a solid if not outstanding pitching staff, a brilliant and feisty manager in Durocher, and, more critical for Stoneham, an enthusiastic fan base. The Giants drew 1,155,067 for home games during the 1954 season, more than they had in five years. With such a result and so much promise, Stoneham was poised for a great run. Happy days seemed here again.

The baseball gods are fickle and cruel, however. The Giants perch atop the heights of New Yorks sporting world would be momentary, and their reign as world champions brief, lasting only one season. They would not enjoy such glory for another fifty-six years, and in a likeness and at a location that could not have been even remotely imagined by mid-1950s New Yorkers.

ONE

Sunset in New York

By the summer of 1955, Horace Stoneham began to sense the dire circumstances of playing baseball in the Polo Grounds. A true Manhattanite with genuine affection for the city and the urban life it offered, he had been willfully blind to the growing number of empty seats in his ballpark in the hopes that the Giants might catch fire and climb back into the National League pennant race. Stonehams connection to New York was not just as a lifelong resident but also through baseball. Born in New Jersey, he moved with his parents to Manhattan as a young boy and except for a few years in boarding schools such as Hun and Pawling and a six-month stint working out west as a twenty-year-old, he spent his entire life in the city. His father, Charles A. Stone-ham, bought the Giants in 1919. Soon thereafter young Horace began lifelong employment with the ball club, beginning in 1924 with ticket sales, gradually moving to field operations, travel arrangements, and eventually working his way into the front office in the early 1930s. He learned the operations of player personnel, salaries, and trades from his father, from John McGraw, a fellow owner and manager of the ball club, and from Bill Terry, who would succeed McGraw as team manager in 1932. When Charles Stoneham died suddenly in January 1936, Horace, now almost thirty-three years of age, became the youngest baseball owner in National League history. Given his family connection, Horace always felt that his ball club was an integral part of New York history. This assumption made the present circumstances of so many empty seats in the ancient Polo Grounds particularly troubling in a deeply personal sense.