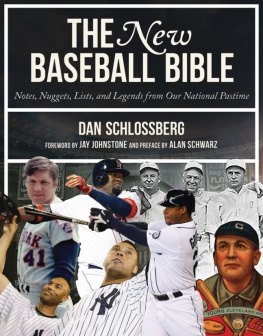

Black Baseball, 1858 1900 Also by James E. Brunson III The Early Image of Black Baseball: Race and Representation in the Popular Press, 18711890 (McFarland, 2009) Black Baseball, 18581900 A Comprehensive Record of the Teams, Players, Managers, Owners and Umpires James E. Brunson III Foreword by John Thorn Volume 1 : Foreword; Preface; Introduction; Black Baseball Subcultures (Essay); Team Profiles; Club Rosters; Team Contacts

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Je f ferson, North Carolina Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Names: Brunson, James E. (James Edward), 1954 author. Title: Black Baseball, 18581900 : A Comprehensive Record of the Teams, Players, Managers, Owners and Umpires / James E. Brunson III ; Foreword by John Thorn.

Description: Jefferson, North Carolina : McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2019 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: Volume 1. Introduction: The Scribbling Class They Covered Themselves in Glory: The Lost Baseball World of the New Negro (Essay) Team Profiles, 1858/1900 Club Rosters, 1858/1900 Directory: Managers, Promoters, and Other Contacts, 1867/1900 Volume 2: Brothers and Brotherhood: Black Baseballs Family Networks (Essay) Empire and Pastime: The Objectification of Black Baseball (Essay) Player Register, A/L Volume 3: Player Register, M/Z A Matter of Ability, and Not Color: Umpires and Team Contacts (Essay) Black Umpires: A Chronology of Games, 1858/1900 The Politics of Performance: Music, Minstrelsy and Black Baseball (Essay). Identifiers: LCCN 2018032704 | ISBN 9780786494170 (paperback : acid free paper) Subjects: LCSH: BaseballUnited StatesHistory19th century. | Negro leaguesHistory19th century. | African American baseball team ownersBiography. | African American baseball umpiresBiography. | African American baseball managersBiography. | BaseballRecordsUnited States. | Discrimination in sportsUnited StatesHistory. | Discrimination in sportsUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC GV863.A1 B7848 2019 | DDC 796.35709034dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018032704 British Library cataloguing data are available ISBN (print) 978-0-7864-9417-0 ISBN (ebook) 9781-47661658-2 2019 James E. Brunson III. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Front cover illustration by James E. Brunson III Printed in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com To my wife, Kathleen; my daughters, Takarra and Tamerit; my mother, Lucille Brunson; and the rest of my family for their patience and love Acknowledgments Many people helped in the making of this work. Willard Draper, as usual, listened with care and shared his thoughts.

Special love and thanks to my wife Kathleen, and her continued patience and support. The NINE and Jerry Malloy Conference remain supportive. I am thankful to John Thorn, Larry Gerlach, Trey Strecker, Geri Strecker, Larry Lester, Dick Clark, Lisa Doris Alexander, Ted Knorr, Todd Peterson, Rebecca Alpert, and Leslie Heaphy who have supported my efforts. Research for the book has been conducted over the past 25 years and took me to all parts of the country. By the mid-2000s, electronic technology began to play a crucial role even though I have been mindful that many old newspapers recently digitized have corrupted over time have limitations. I still love the stale aroma of old libraries and printed materials.

I want to thank the following institutions: Northern Illinois University, University of Texas-Austin, University of Chicago, University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana, University of Illinois-Springfield, University of Memphis, Chicago History Museum (formerly the Chicago Historical Society), University of Maryland at College Park, University of California-Berkeley, Emory University, Du Sable Museum (Chicago), Newark Public Library, Tulane University, Library of Congress, the St. Louis Public Library, and a host of other libraries and historical societies. Table of Contents Foreword by John Thorn A feature film, titled , about Jackie Robinsons breaking of Major League Baseballs color barrier in 1947, enjoyed much success in 2013. The screenwriters got the story right, largely. However, a film will take dramatic license that the written word may not. Like the newsman in the great western picture The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance , the director of must say, This is baseball, folks.

When the legend becomes fact, print the legend. To a greater extent than Hollywood, a historian is obliged to follow the trail of fact. It diminishes Rickey and Robinson not one bit to think about all those black players of long ago who built the bridge, as my friend Buck ONeil said, that Jackie Robinson walked across. James Brunson knows that. The stars of the Negro Leagues are now ensconced in Baseballs Hall of Fame, but the bridge to Cooperstown was built by men who barbered and bootblacked, waited table and laundred linens, men who played baseball whenever they could. Even in its cradle, baseball was bound up with the issue of inclusion and exclusionwhom do we , the entrenched class, permit to play alongside us ? In New York City around 1840 there were those who thought the newly codified game of baseball should model cricketas a diversion for gentlemen, those with sufficient money and thus leisure to play an afternoons game of ball.

Clubs of working-class origin followed soon enough, to the dismay of the white-collar crowd. A largely Irish club, the Magnolia, formed in 1843; a more celebrated and long-lived one, the Atlantic, was created in Brooklyn in 1855. The first African American clubs, three in number, were thought to have been from Brooklyn as well, beginning in 1859: the Unknowns, the Monitors, and the Uniques of Williamsburgh were in the field that season, but recently a reference in the press turned up to a St. Johns colored club in Newark, New Jersey, going back to 1855. In truth, young people of both colors and genders had played a game they called baseball long before men from New York took to organizing clubs and restricting membership. African Americans had played baseball near Madison Square in the 1840s, not far from the grounds of the New York and Knickerbocker clubs before they relocated to Hobokens Elysian Fields.

Researchers had found references to ball play by antebellum slaves in the South, but no evidence was put forth that the game they played was baseball as we might understand ita game that went by that name, or one that bore the central feature of bases run in the round. (In Massachusetts well into the 1850s, for example, the names base ball and round ball were used interchangeably to describe the same game.) Frederick Douglass, Sr., wrote in his autobiography, published in 1845, that at holiday time by far the larger part [of slave communities] engaged in such sports and merriments as ball playing, wrestling, running foot races, fiddling, dancing, and drinking whiskey: and this latter mode of spending the time was by far the most agreeable to the feelings of our masters. But in a Kingston, New York, newspaper of August 19, 1881, an elderly barber recalled that in 1820 or soseven years before the peculiar institution was abolished in New York Statehe and his fellow slaves had played baseball. We used to have a great deal better time than that you do now, said Mr. [Henry] Rosecranse, born in 1804. We didnt have a big city with lamps and curb stones and paved walks, and had to go round through the mud, but we had more holidays.

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Je f ferson, North Carolina Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Names: Brunson, James E. (James Edward), 1954 author. Title: Black Baseball, 18581900 : A Comprehensive Record of the Teams, Players, Managers, Owners and Umpires / James E. Brunson III ; Foreword by John Thorn.

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Je f ferson, North Carolina Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Names: Brunson, James E. (James Edward), 1954 author. Title: Black Baseball, 18581900 : A Comprehensive Record of the Teams, Players, Managers, Owners and Umpires / James E. Brunson III ; Foreword by John Thorn.