IMAGES

of America

MORGAN

COUNTY

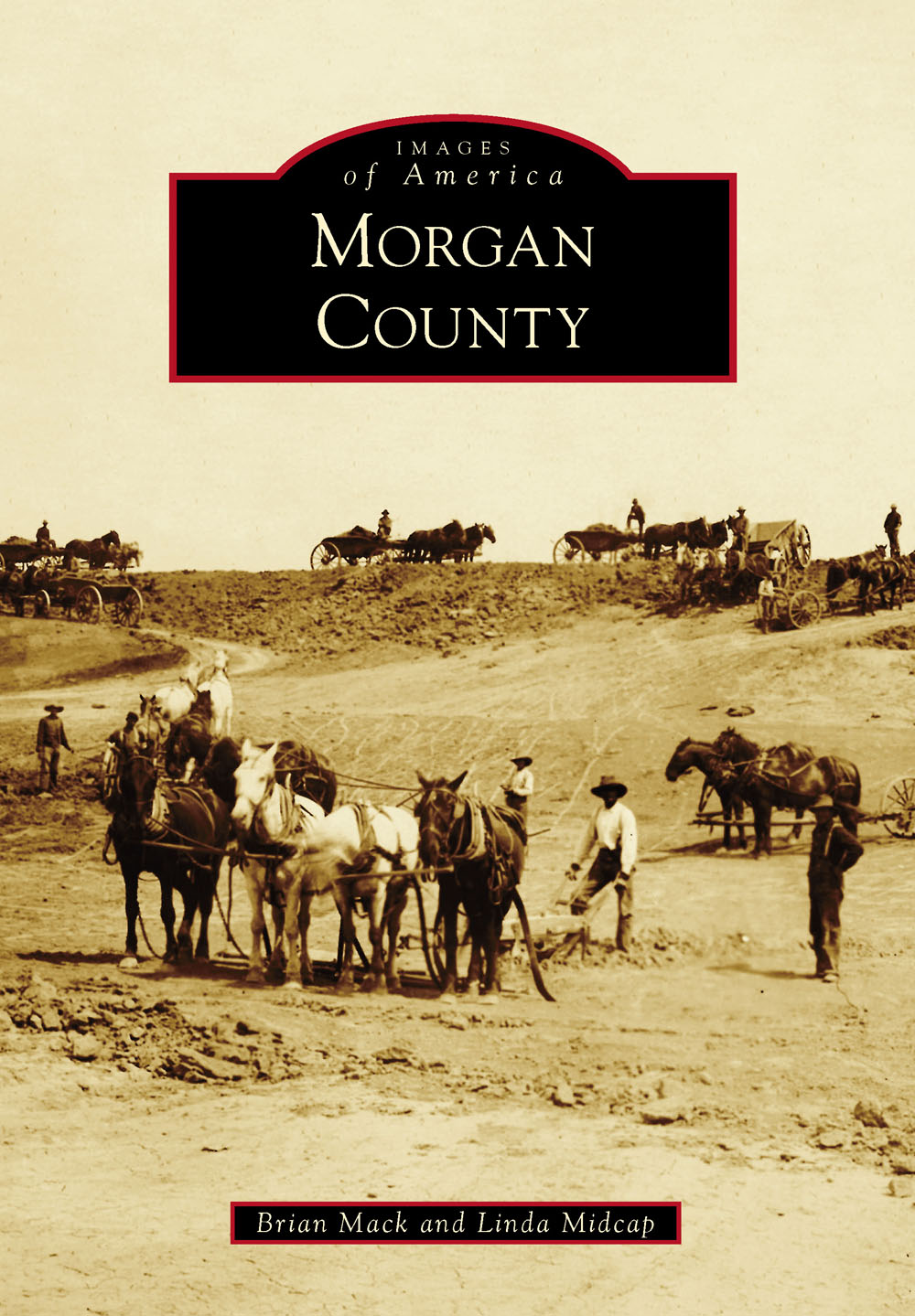

ON THE COVER: Bob Atchisons construction crew is pictured here building thee Empire Reservoir dam around 1907. Clarence M. Work and Cree Work are included in the photograph. Empire Reservoir is part of the Bijou Irrigation District. (Courtesy of the Fort Morgan Museum.)

IMAGES

of America

MORGAN

COUNTY

Brain Mack and Linda Midcap

Copyright 2016 by Brian Mack and Linda Midcap

ISBN 978-1-4671-1565-0

Ebook ISBN 9781439655214

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015947747

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

The Fort Morgan Heritage Foundation is pleased and proud to publish this pictorial history of Fort Morgan and Morgan County. This book includes many photographs of the lives and times of our forebears, who took part in the birth and growth of Fort Morgan and Morgan County. We can see in this book the changes in how things were in the past and how they are today. Our forebears were strong and courageous people with dreams, visions, and foresight who built a community that promised prosperity, safety, and security. We learn from the past to improve the ways of the present. It is a never-ending progression. The mission statement of the heritage foundation and the Fort Morgan Museum reads: The Fort Morgan Museum deals primarily, but not exclusively, with the history and culture of the people of northeastern Colorado, through collecting, preserving, interpreting, researching, and exhibiting materials reflecting the diverse history and traditions of the area. We serve as a depository for historical items and records and act as the educational and informational center for the community.

The Fort Morgan Heritage Foundation is open to everyone. A governing board consisting of 17 volunteers meets monthly to assist the professional museum staff in charting the course of the museum programs, publications, and exhibits.

Donald A. Ostwald Sr.

President, Fort Morgan Heritage Foundation

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

As a community, Morgan County has a fascinating history, and we are delighted to be able to shed a light on some of the people, places, businesses, and events that have made that history so rich. While this book contains only a shadow of everything that has made Morgan so special, we hope that readers are able to get a sense of the community we have long considered to be home. Compiling the photographs and information in this book was a rewarding work of intrigue, as we learned more about Morgan County than expected. This endeavor could not have been completed without the assistance of the following contributors: Walter Barrett, Merle and Margie Bristol, James Butler, Sara Canfield, City of Fort Morgan, Kay Coffin, Gerty Chapin, Jerry Cooper, Community History Writers, Sue Christensen, Bethany Crandell, Lyn Deal, Thelma Downing, Fort Morgan Museum, Fort Morgan Times, Timmy Fritzler, Jenni Grubbs, Jenese Hankins, Gail Hawkins, Heritage Foundation, Barb Keenan, Chandra McCoy, Maxzine Lorenzini, Viviane Lorenzini, Dave Luna, O.J. Metzger, Jo Ostwald, Anne Overturf, Lanny Page, Dave Roberts, Gerry Thiel, McKinley Thompson, and Kathy Wood.

Unless otherwise noted, all images are courtesy of the Fort Morgan Museum.

INTRODUCTION

Like the oceans, and mountain ranges, the enormity of the prairies was a natural barrier to Western settlement and possible enemy incursions. Until the last half of the 19th century, the inhospitable plains were dreaded as never-ending monotonous miles by those early European and American explorers and trappers who traveled them. To the Native Americans, primarily seminomadic Arapahoes and Cheyennes, the northeast Colorado area, which provided food, shelter, clothing, trading goods, religion, and culture, was their home. They hunted bison, antelope, deer, and other plains animals. Some wintered there, protected by bluffs in dry creeks such as the Wildcat and Bijou. They did not own the land but claimed the territory as theirs and would fight to keep their sovereignty over it.

The first explorers, mountain men, military men, and traders found little to entice them to settle. The vast, treeless, dry, seemingly endless landscape hid its potential under its sea of grass. They saw little beauty and found no riches in its vast horizon or in the subtle hues of the many grasses and plants, so they hunkered down and endured, getting through it as quickly as possible.

After the Louisiana Purchase, and the success of the Lewis and Clark expedition, Zebulon Pike led a military expedition of exploration, whose tasks were to assess, survey, and map the prairie territory in 1806. In 1820, Stephen Long, who led another expedition of exploration, followed the South Platte River until it reached the Rocky Mountains. Long wrote about an orchard after camping by a large cottonwood grove near the river, and later, traders named the spot Fremonts Orchard. Both Pike and Long described the high plains as becoming, in time, as celebrated as the sandy deserts of Africa. Neither believed any form of agriculture would be successful. Both were wrong.

The discovery of gold in the Colorado mountains in 1858 created the impetus for growth in northeastern Colorado. First, stagecoach stops and pony express stops were created to facilitate mail and supplies as well as transportation for prospectors and others attracted by the promise of wealth.

In 1864, a fort was built on the bluffs overlooking the river and the natural ford at Muir Springs to protect wagon trains and act as a deterrent to Indian attacks. Galvanized Yankees (captured Confederate soldiers who volunteered to serve in the Union army, fighting Indians in the West rather than languish in prisoner-of-war camps) as well as Union troops manned the fort.

The fort, named for a popular Union officer who, ironically, never saw the fortress, only existed for four years because, by 1868, most of the Plains Indians had been forcibly removed to reservations, the bison were being systematically slaughtered, and there was no longer a need for protection for wagon and supply trains. Also, the Union Pacific Railroad had completed a line to Cheyenne, Wyoming, and settlers began to come by rail to claim land under the Homestead Act.

With the Native Americans and bison gone, the vast acres of lush buffalo grass offered fantastic opportunities to ranchers such as cattle kings John W. Iliff and Jared Brush, who grazed thousands of cattle in the eastern third of the state.

Their dominance was challenged by the successful creation of an irrigation canal (1882) in Weldon Valley, the brainchild of those who believed that water could turn the desert into an Eden, and soon homesteaders began to settle in the valley.

The popularity of the Homestead Act and Timber Act, as well as the disruption of the Civil War, led many men and women to envision a brighter, independent future in the West. Abner S. Baker, a Civil War veteran, joined Horace Greeleys Union Colony Number One. While hunting buffalo near Beaver Creek, he realized that the unplowed land could be fertile if water could be brought from the river by canal.

In 1884, Baker completed the Platte and Beaver Ditch and platted the townsite. Modestly, he named the new community after the fort. Many of our founding families came from Baraboo, Wisconsin, and were part of Bakers extended family; others came from Canada and eastern states. They shared common Protestant religious traditions, conservative Republican political views, and entrepreneurial ideals. They were old-stock Americans whose ancestral roots were predominately English, Scottish, and Scots Irish. They recruited settlers like themselves, advertising for thrifty, serious, wholesome families who would work hard and do their civic duty. They believed in temperance and believed that adversity and personal obstacles created opportunities for persistence, self-discipline, and faith.

Next page