PUBLISHER: Amy Marson CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Gailen Runge EDITORS: Karla Menaugh and Liz Aneloski TECHNICAL EDITOR: Debbie Rodgers COVER DESIGNER: Page + Pixel BOOK DESIGNER: April Mostek PRODUCTION COORDINATOR: Tim Manibusan PRODUCTION EDITORS: Jennifer Warren and Nicole Rolandelli ILLUSTRATOR: Valyrie Gillum PHOTO ASSISTANTS: Carly Jean Marin and Mai Yong Vang STYLE PHOTOGRAPHY by Lucy Glover and INSTRUCTIONAL PHOTOGRAPHY by Diane Pedersen of C&T Publishing Inc., unless otherwise noted Published by Kansas City Star Quilts, an imprint of C&T Publishing, Inc., P.O. Box 1456, Lafayette, CA 94549  DEDICATION To my supportive and understanding husband, Jim; my children, Lauren and David, and their respective spouses, Clay and Alyson; and my grandchildren, Lucy, Joshua, and Rileythe loves of my life. All of you encourage and inspire me every day to smile and laugh and enjoy the journey. To my grandmother, Louise Middleton Davis Firman, who taught me to sew, and to my mother, Jacque Davis Eades, who taught me to love and appreciate antiques. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A great big thanks to everyone who has helped me during the process of writing this book. So many people have encouraged me along the way.

DEDICATION To my supportive and understanding husband, Jim; my children, Lauren and David, and their respective spouses, Clay and Alyson; and my grandchildren, Lucy, Joshua, and Rileythe loves of my life. All of you encourage and inspire me every day to smile and laugh and enjoy the journey. To my grandmother, Louise Middleton Davis Firman, who taught me to sew, and to my mother, Jacque Davis Eades, who taught me to love and appreciate antiques. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A great big thanks to everyone who has helped me during the process of writing this book. So many people have encouraged me along the way.

To my friend, author, designer, and fellow quilter Betsy Chutchian, who gave me the push to pursue my desire to write this book. To my talented and inspiring stitch groups, who love quilting, sewing, and reproduction fabrics as much as I do and always feed my passion for creating. To my patient and long-suffering editor, Karla Menaugh, and the fantastic C&T team, who took my ideas and transformed them into this wonderful book. To my hard-working machine quilters, Sheri Mecom and Kerry Coburn, who took my creations and turned them into beautiful family heirlooms.  Introduction I have a passion for quilts, and blue quilts are my favorites. Because the indigo plant has been around for centuries, the availability of its reliable and stable dye made it possible to create blue fabrics that have survived over time.

Introduction I have a passion for quilts, and blue quilts are my favorites. Because the indigo plant has been around for centuries, the availability of its reliable and stable dye made it possible to create blue fabrics that have survived over time.

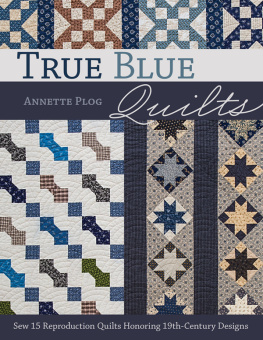

The blue-and-white quilt is one of the most desirable antiques, and these quilts can still be found in good condition. This book will help you identify blue fabrics from the 1800s. Learning the characteristics of blue fabrics in the nineteenth century can help in revealing the age of an antique quilt. Reproducing antique quilts has been made possible by wonderful, historically correct reproduction fabrics. Most fabric manufacturers feature lines of reproduction fabrics, and some lines are dated. True Blue Quilts features fifteen quilt projects that represent patterns and blue fabrics found in the nineteenth century. True Blue Quilts features fifteen quilt projects that represent patterns and blue fabrics found in the nineteenth century.

Each chapter covers a specific time period and features the blue fabrics of that time. I hope that this book encourages you to learn a little about the history of blue fabrics and provides an inspiration for you to design and create your own heirlooms. Enjoy the projectsand always choose blue!  A Quick Blue Fabric Study Guide Fabrics, whether antique or reproduction, will always give you hints about their age. You just need to know where to look. Here is a little information that will help you determine what period a fabric represents. If you need more guidance, there are more intensive study guides and books.

A Quick Blue Fabric Study Guide Fabrics, whether antique or reproduction, will always give you hints about their age. You just need to know where to look. Here is a little information that will help you determine what period a fabric represents. If you need more guidance, there are more intensive study guides and books.

I hope this information will spark your interest and inspire you to learn more. See Resources for a list of books about dating fabrics and a list of companies that produce reproduction fabrics. EARLY CENTURY: 1840S AND EARLIER During the early years in America, little fabric was produced domestically. The little fabric that was produced was locally woven, and the dyes were naturally produced. Domestic fabrics were usually used in clothing and pieced quilts, whereas imported fabrics, which mostly came from Europe or Asia, were more commonly used for bedcovers and upholstery. Indigo blues were one of the first fabrics produced in America due to the availability of indigo from farms that developed in the South.

The dye from the indigo plants was relatively stable and reliable. Europe prohibited skilled textile workers from coming to America, keeping a tight hold on fabric production in the late 1700s. Some textile workers began to immigrate secretly to America, and they brought important knowledge needed for fabric production. In 1793, Eli Whitney developed the cotton gin, a machine that separated the cotton from the seed. This made working with cotton quicker and easier. Americans began building textile mills and powered looms that helped fabric manufacturing to grow successfully and produce much more fabric in America.

Blue fabric was an early favorite. Colors that were commonly paired with blue included browns, creams, chromes, and reds. Prints Roller prints, stamped prints, wovens, grounds, small figures, chintz, French toiles, large-scale prints, pillars, panels, swags, floral bouquets, flowers, geometrics, vines, serpentine stripes Colors Indigo: a very dark blue Prussian blue: a vivid blue-green Lapis: a blue with a red print Indigo with a white or chrome print: made from a dyeresistant print stamped on the fabric before it was dyed  Examples of early blue fabrics Block Designs Wholecloth, medallions, strip quilts, pieced blocks, stars, Nine-Patch, Four-Patch, squares on point, large quilts for beds

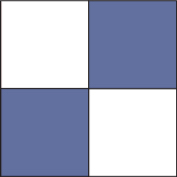

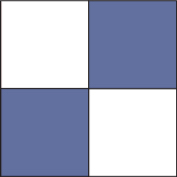

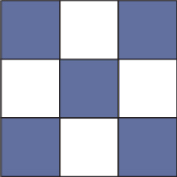

Examples of early blue fabrics Block Designs Wholecloth, medallions, strip quilts, pieced blocks, stars, Nine-Patch, Four-Patch, squares on point, large quilts for beds  Four-Patch block

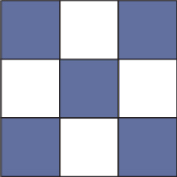

Four-Patch block  Nine-Patch block

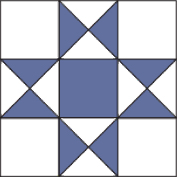

Nine-Patch block  Flying Geese block

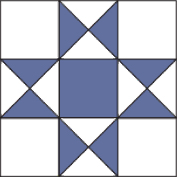

Flying Geese block  Ohio Star block

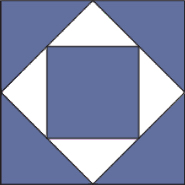

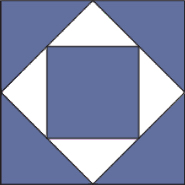

Ohio Star block  Square-in-a-Square block MID CENTURY: 18401870 With Americas independence decided, the Industrial Revolution began. The cotton gin, domestic textile mills, imported European fabrics, and the sewing machine made quiltmaking more affordable and desirable. America was still importing British and French cottons, but American textile manufacturing made fabric more easily attainable for most families. Cotton from the South was plentiful, domestic textile mills were producing fabrics, and America was growing westward.

Square-in-a-Square block MID CENTURY: 18401870 With Americas independence decided, the Industrial Revolution began. The cotton gin, domestic textile mills, imported European fabrics, and the sewing machine made quiltmaking more affordable and desirable. America was still importing British and French cottons, but American textile manufacturing made fabric more easily attainable for most families. Cotton from the South was plentiful, domestic textile mills were producing fabrics, and America was growing westward.

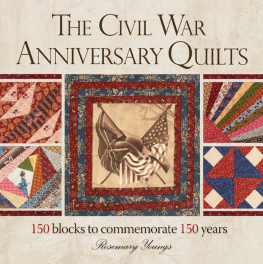

When the American Civil War began, little fabric was produced. Any cotton grown and harvested in the South could not be sold. The Southern seaports were blockaded by the Union, so cotton could not be exported and fabrics from Europe could not be imported. Northern mills would not purchase cotton from the South because they did not want to monetarily support the South. With the fabrics they had or could obtain, Southern and Northern women were making uniforms, flags, quilts, and blankets for the soldiers. Treasured heirlooms were hidden, protecting them from being destroyed by fire, soldiers, or thieves.

Next page

DEDICATION To my supportive and understanding husband, Jim; my children, Lauren and David, and their respective spouses, Clay and Alyson; and my grandchildren, Lucy, Joshua, and Rileythe loves of my life. All of you encourage and inspire me every day to smile and laugh and enjoy the journey. To my grandmother, Louise Middleton Davis Firman, who taught me to sew, and to my mother, Jacque Davis Eades, who taught me to love and appreciate antiques. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A great big thanks to everyone who has helped me during the process of writing this book. So many people have encouraged me along the way.

DEDICATION To my supportive and understanding husband, Jim; my children, Lauren and David, and their respective spouses, Clay and Alyson; and my grandchildren, Lucy, Joshua, and Rileythe loves of my life. All of you encourage and inspire me every day to smile and laugh and enjoy the journey. To my grandmother, Louise Middleton Davis Firman, who taught me to sew, and to my mother, Jacque Davis Eades, who taught me to love and appreciate antiques. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A great big thanks to everyone who has helped me during the process of writing this book. So many people have encouraged me along the way. Introduction I have a passion for quilts, and blue quilts are my favorites. Because the indigo plant has been around for centuries, the availability of its reliable and stable dye made it possible to create blue fabrics that have survived over time.

Introduction I have a passion for quilts, and blue quilts are my favorites. Because the indigo plant has been around for centuries, the availability of its reliable and stable dye made it possible to create blue fabrics that have survived over time. A Quick Blue Fabric Study Guide Fabrics, whether antique or reproduction, will always give you hints about their age. You just need to know where to look. Here is a little information that will help you determine what period a fabric represents. If you need more guidance, there are more intensive study guides and books.

A Quick Blue Fabric Study Guide Fabrics, whether antique or reproduction, will always give you hints about their age. You just need to know where to look. Here is a little information that will help you determine what period a fabric represents. If you need more guidance, there are more intensive study guides and books. Examples of early blue fabrics Block Designs Wholecloth, medallions, strip quilts, pieced blocks, stars, Nine-Patch, Four-Patch, squares on point, large quilts for beds

Examples of early blue fabrics Block Designs Wholecloth, medallions, strip quilts, pieced blocks, stars, Nine-Patch, Four-Patch, squares on point, large quilts for beds  Four-Patch block

Four-Patch block  Nine-Patch block

Nine-Patch block  Flying Geese block

Flying Geese block  Ohio Star block

Ohio Star block  Square-in-a-Square block MID CENTURY: 18401870 With Americas independence decided, the Industrial Revolution began. The cotton gin, domestic textile mills, imported European fabrics, and the sewing machine made quiltmaking more affordable and desirable. America was still importing British and French cottons, but American textile manufacturing made fabric more easily attainable for most families. Cotton from the South was plentiful, domestic textile mills were producing fabrics, and America was growing westward.

Square-in-a-Square block MID CENTURY: 18401870 With Americas independence decided, the Industrial Revolution began. The cotton gin, domestic textile mills, imported European fabrics, and the sewing machine made quiltmaking more affordable and desirable. America was still importing British and French cottons, but American textile manufacturing made fabric more easily attainable for most families. Cotton from the South was plentiful, domestic textile mills were producing fabrics, and America was growing westward.