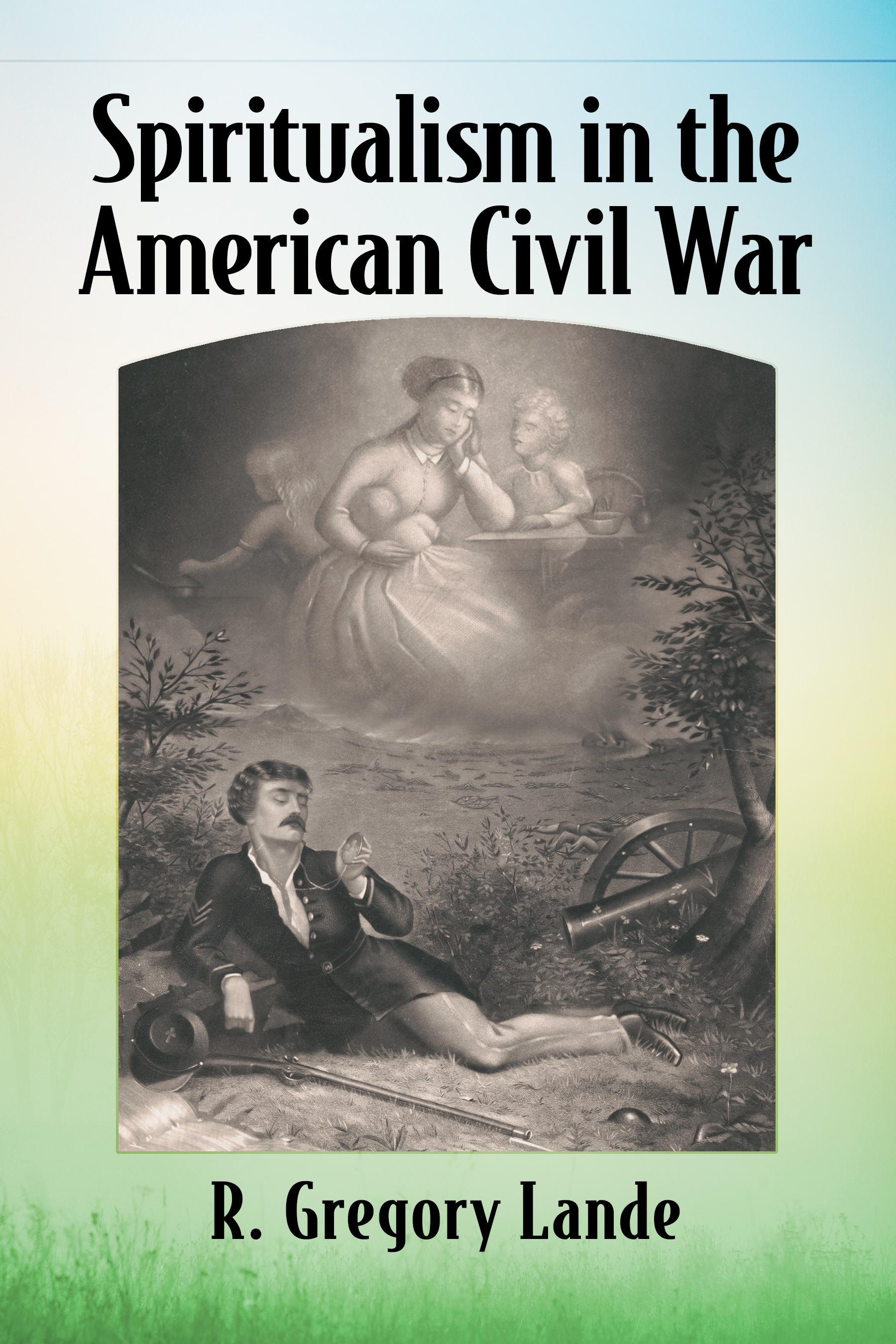

Spiritualism in the American Civil War

Also by R. Gregory Lande

Psychological Consequences of the American Civil War (McFarland, 2017)

Spiritualism in the American Civil War

R. Gregory Lande

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Names: Lande, R. Gregory, author.

Title: Spiritualism in the American Civil War / R. Gregory Lande.

Description: Jefferson, North Carolina : McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020026899 | ISBN 9781476682235 (paperback : acid free paper) ISBN 9781476640181 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: SpiritualismUnited StatesHistory19th century | United StatesHistoryCivil War, 1861-1865Psychological aspects.

Classification: LCC BF1242.U6 L36 2020 | DDC 133.9073/09034dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020026899

British Library cataloguing data are available

ISBN (print) 978-1-4766-8223-5

ISBN (ebook) 978-1-4766-4018-1

2020 R. Gregory Lande. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover image: The dying soldiers circa 1870 engraving (Library of Congress)

Printed in the United States of America

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Historical research supplied the framework for Spiritualism in the American Civil War , but the foundation was built by two others. Brenda Lande, my wife, provided support and encouragement, and cast a critical eye when proofreading the manuscript. Our son Galen Lande is a fountainhead of creativity and technical prowess, an everlasting source of inspiration that kept this project moving forward.

Table of Contents

Preface

A Civil War soldiers silence was unsettling. For family and friends left behind at home, the letters from loved ones made up one of the few connections spanning the geographic gulf, an emotional bridge tenuously dependent on rickety mail service. When letters failed to inform, the next best source of information was newspapers, describing distant battles and perfunctorily citing casualties. Scanning the list might reveal a soldiers fate: perhaps killed in battle, injured, or taken prisoner. In most cases the readers interest was unfulfilled, leaving the emotional emptiness intact. In some cases a fellow soldier or a government communiqu brought news of a loved ones fate.

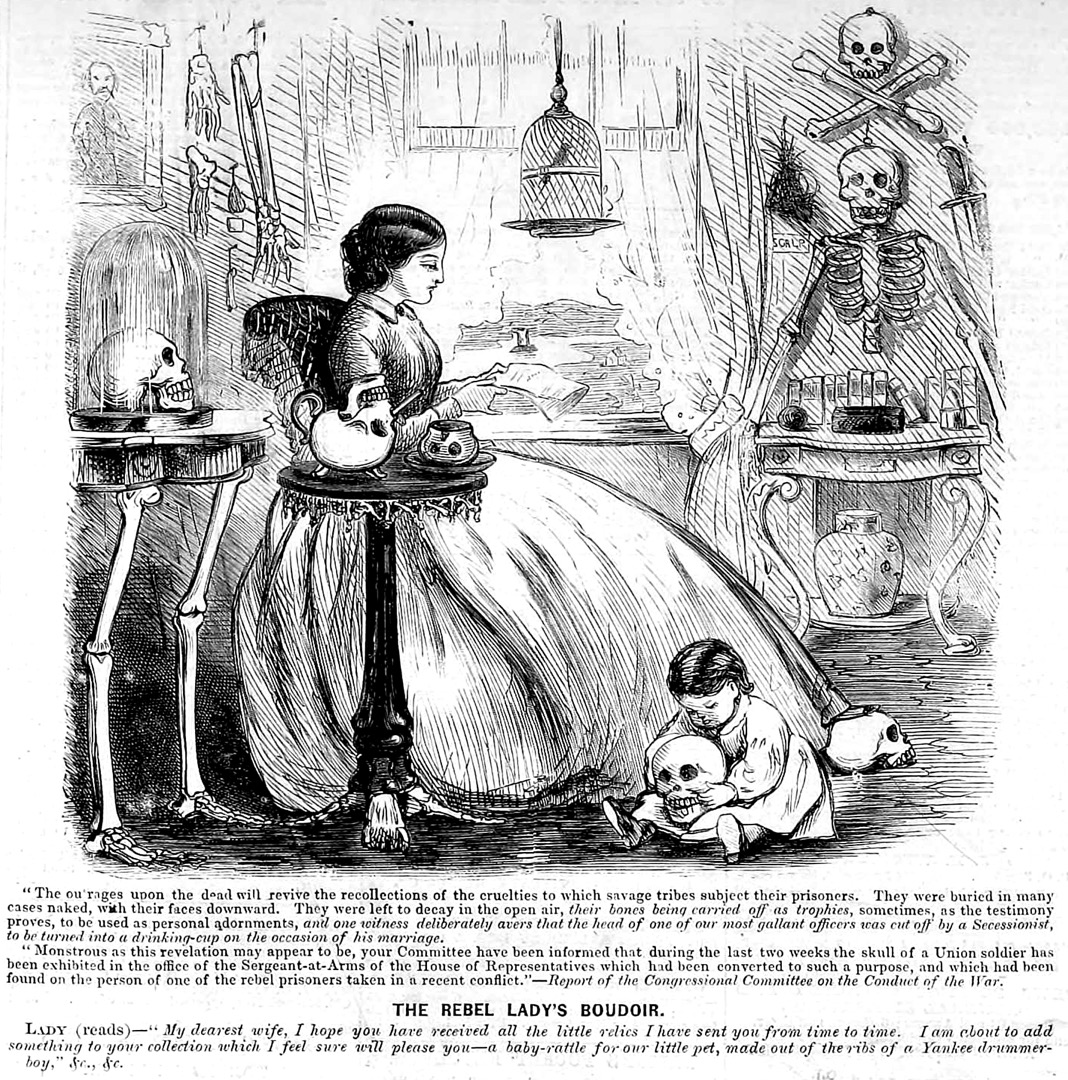

When soldiers died on the battlefield, enmity and the exigencies of war often extracted a terrible toll, not the least of which was stripping the last trappings of humanity from the soldiers as their nameless, shattered corpses littered the area. As word of the carnage reached distant cities the resulting anguish fed further calls for retribution, fanning the flames of hatred that would burn for decades.

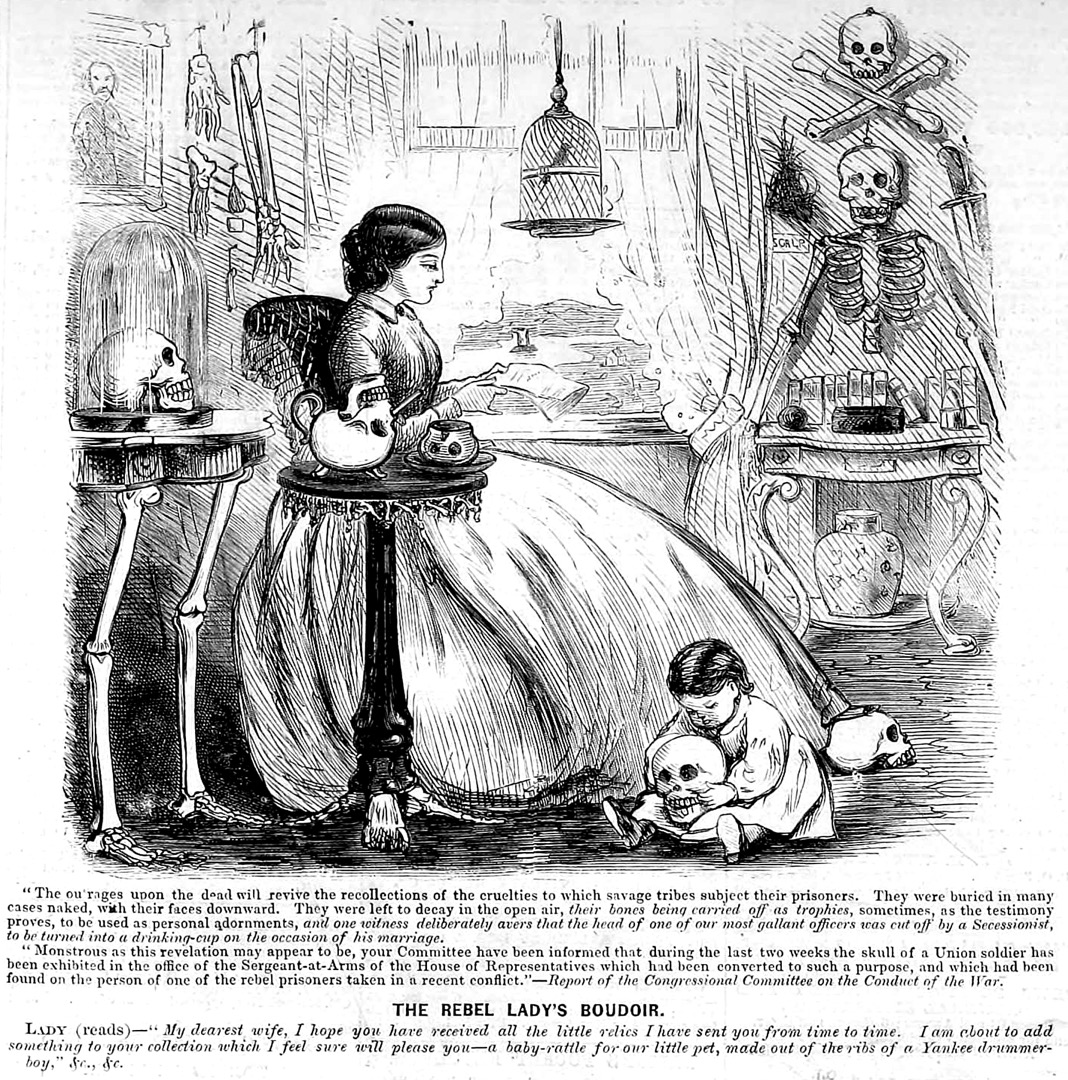

The Rebel rout of Union forces at the First Battle of Bull Run provided some of the first fuel that provoked scorching recriminations in Washington, as angry politicians brought forth soldiers denouncing a long list of the enemys inhumanities. In a harbinger of the atrocities to come, a young soldier testified before members of the U.S. Senate that the dead laid upon the field unburied for five days. Another witness bitterly recalled how Union soldiers were buried in many cases naked, with their faces downward; they were left to decay in the open air; their bones were carried off as trophies. Northern newspapers seized on these stories of battlefield atrocities and flagrantly denounced the adversary with lurid depictions of battlefield desecration.

The outrages on the dead ( Frank Leslies Illustrated Newspaper , May 17, 1862).

As might be imagined, the Confederates description of the Manassas battlefield differed in tone, accusing Union officials of minimizing their losses as part of a ham-fisted , shameless cover-up . The actual loss of the enemy will never be known, it may now only be conjectured. Their abandoned dead, as they were buried by our people where they fell, were not enumerated, but many parts of the field were thick with their corpses, as but few battle-fields have ever been.

The first battles of the Civil War started a trend that continued in the following years, with fallen soldiers hastily buried in shallow graves, an ignominious end that consigned countless corpses to an everlasting anonymity and left families futilely waiting for closure. Filling the void for some was Spiritualism, which supposedly not only brought together lost loved ones, erasing the timeless boundary separating the living from the dead, but also promised a glorious eternal reunion in the afterlife.

Driven by desperation and dysphoria, an untold number of Americans sought the services of psychic mediums both during and after the war. An estimate of the number of spiritualists is at best guesswork, but one observer notably claimed nine million believers in 1861, a figure that supposedly grew to 11 million by 1867.

A more accurate head count during the waning phase of the religions growth in the late nineteenth century came from spiritualists reporting 334 organizations, with 30 regular church edifices, not including halls, pavilions, and other places owned or occupied by them. There are 45,030 members. While the real numbers will never be known, Spiritualisms influence on society is less debatable, an outsized impact spread by newspapers and magazines of the day chronicling its controversies and curiosities.

Spiritualism in the American Civil War pieces together Spiritualisms disparate historical threads, weaving a dark cloak behind which it hid exploitation and deceit. American Spiritualisms ascendancy and ancestry are, in major part, direct descendants from animal magnetism. The therapeutic use of magnets can be traced to ancient times, but their rediscovery and medical application in the eighteenth century was a watershed event showering seedlings that would later sprout animal magnetism, mesmerism, patent medicines, and Spiritualism: all covered by a dense thicket of controversy limiting the growth of legitimate medical magnetism.

For the author, the journey writing this book began with a simple but sobering assessment. Human emotions transcend time, and the loss of a loved one provoked anguish then no different from now. What differed was the sizeable segment of Civil War-era Americans who questioned deaths imponderability and particularly its inevitability by shunning established philosophy, religion, and science for Spiritualisms soothing sophisms.

Clearly, Americas Civil War created seismic shifts, an earth-shattering social tumult upending long cherished traditions. As wrenching as it was, by itself this disruption was not enough to shake peoples faith. Newspapers and other publications increasingly informed the public about various scientific discoveries such as electricity and magnetism, mysterious forces hijacked by peddlers in pretense, an assorted group that included patent medicine makers, traveling medicine men, and stage-struck spiritualists. Patent medicines bottled belief behind labels touting cures from an electric or magnetic medicine, while savvy spiritualists sought sanctuary from suspicion by likening their faith to those same invisible forces.