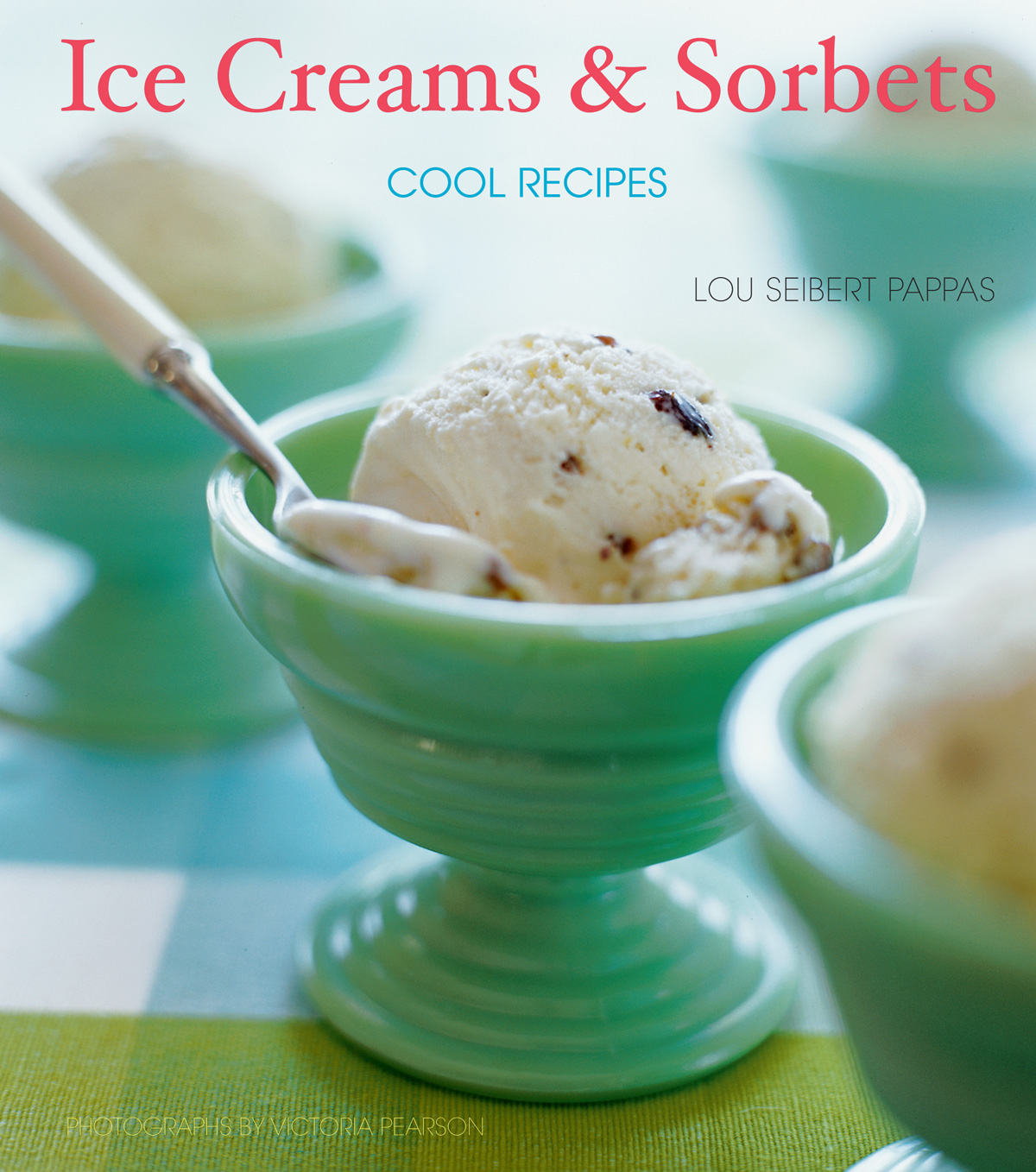

Its fascinating to consider the changes in ice cream over the years. My passion for this luscious, cool, sweet crystallized in childhoodI got to lick the dasher of the homemade vanilla bean, peppermint, chocolate, and fresh strawberry ice creams. Later with home refrigerator-freezers, we indulged in packaged ice creams, as churning the homemade version seemed old-fashioned and a bother working with ice and salt. Then many trips to Europe, sampling sorbets, gelati, and ices in Italy, France, and Scandinavia, reignited my love for making my own. Plus the new, small, electric ice cream freezers made it a breeze!

When I wrote a previous book in the nineties, the recipe collection drew on my best samples of trips abroad and in America. The recipes featured the pistachio, framboise, and cafe flavors from Berthillon, the Parisian shop that schoolchildren adore. They covered stellar citrus and berry sorbets from three-star Michelin restaurants and fresh fruit ices from Turkey South Africa, and Malaysia. Gelati were Grand Marnier and rum raisin versions from Florence, and the treat from Tivoli in Scandinavia was ultracreamy almond praline.

Today frozen desserts are in the spotlight, with endless complexity in their flavors and presentations and the great delight they offer.

Yet what is really fun is to create your own. You can achieve silky, satiny ice cream unadorned with additives. You can turn out healthful, pure fruit ices and sorbets flaunting the fresh peak-of-season taste.

We are blessed with a wealth of products not widely available a short time ago. Lavender, basil, lemongrass, ginger, rosemary, blood orange, papaya, and exotic melons enhance this collection. Honey red wine, and liqueurs lend an intriguing flavor and an appealing spoonable consistency to the products. In the toppings, balsamic vinegar uplifts berries and caramelized spiced nuts provide a teasing sugary crunch.

There is such a joy in turning seasonal bounty into an almost instant treat. The mix goes together readily in advance for chilling. With todays efficient equipment, ice cream can be churned in a quarter of an hour or so. Sorbets and ices can be easily frozen without a machine. So indulge. One luscious taste calls for another.

Lou Seibert Pappas

THEORY AND TECHNIQUES

Ice cream is basically a liquid mixture that is stabilized by freezing much of the liquid and creating a very fine crystalline structure. The proportion of the ingredients and the preparation technique determine the quality To achieve a fine consistency several factors are important. Proper agitation is one. Others are rapid freezing and the amount of air incorporated.

It is useful to understand the science behind the freezing process. Harold McGee, in his book On Food and Cooking, explains that sugar lowers the freezing point of the solution from 32F to around 27E The dissolved sugar gets in the way of the water molecules that would bond together to form ice crystals. At this temperature the water molecules have slowed enough so that their attraction becomes stronger than the disruptive influence of the sugar. As they crystallize, water molecules are subtracted from the mixture, the remaining solution gets more concentrated with sugar, and the freezing point is lowered further. Even when ice cream is frozen it will still contain some liquid at 0E The desirable temperature for serving is 10E as the proportion of liquid will then yield a semisolid consistency

Therefore, to achieve a fine-quality product, ice creams, sorbets, and ices must have many well-dispersed tiny ice crystals. Otherwise, a few large crystals would yield an icy, coarse product. Though ice creams, sorbets, ices, and still-frozen desserts are considered to be frozen, they are not completely so. Instead, tiny ice crystals are suspended in a binding syrup of sugar, with or without fat and/or protein. While much of the water in the mixture freezes, the concentration of sugar and other substances prevents the dessert from fully solidifying. Cream, milk, and eggs work as buffers to separate tiny crystals from one another. Alternatively liquor, liqueurs, wine, honey and corn syrup lower the freezing point of the mixture, so frozen desserts made with them will usually be softer. These additions are advantageous in homemade ice cream and sorbets, which sometimes get harder than commercial ice creams that have added emulsifiers.

Another influence on the ultimate texture is the amount of air whipped in. When the mixture churns in an ice cream maker, air beaten in helps keep the crystals apart and makes the texture smooth. Once the ice cream begins to thicken and becomes viscous, it starts to retain air well. As home freezers churn, the majority of the aeration happens toward the end of the processing time, producing tiny air pockets.

With ice cream, rapid cooling of the custard during stirring develops many small seed ice crystals and helps to distribute them evenly If the mixture is also stirred while freezing, the ice masses are interfered with and the remaining ice will be in the form of tiny crystals. Ultimately, the more agitation provided, the slower the freezing process, and the tinier the ice crystals.

Granite are an exception to the goal of agitation, as large ice crystals are desired and so stirring is of short duration.

Three stages are involved in the preparation of frozen desserts. They include preparing the mix, freezing it, and ripening or firming it after the freezing process.

FREEZING ICE CREAM

After being frozen in an ice cream maker, ice cream is usually placed in the freezer for 2 hours to firm up, or ripen. This allows the flavors to blend. Ideally ice cream should be stored at fairly low temperatures, between -10 and 0F, to maintain its fine texture and flavor. Cover it tightly so it doesnt pick up off odors and so that moisture does not settle onto its surface, forming large crystals. A sheet of plastic wrap pressed onto the surface of the ice cream is a good idea. The gradual coarsening of texture during freezing is due to repeated partial thawing when serving or from fluctuations in the temperature of the freezer.

Ice crystals grow during storage because whenever ice cream is warmed slightly the smallest crystals melt. When the temperature drops again, the additional water is taken up by the surviving crystals, which get larger and larger. The effect is commonly known as freezer bum. The lower the average storage temperature of the freezer, the less change takes place.

SERVING TIPS

Sorbets, ice creams, ices, and frozen yogurts should be allowed to warm to about 10F before serving for the best flavor and texture. This allows them to achieve a slightly creamy consistency rather than a solid one. If ice cream is firmly frozen, transfer it to the refrigerator for 20 to 30 minutes before scooping and serving, but dont let it thaw too much as repeated thawing and refreezing will degrade its texture. Frozen products with honey corn syrup, liqueur, or other alcohol as an ingredient will initially freeze to a softer consistency and may be spoonable directly from the freezer.

It is helpful to dip your ice cream scoop in a bowl of hot water before each scoop to make neat balls when scooping many servings of ice cream or sorbet.

Granite should be served slightly thawed and slushy They are best served the day they are made, since the ice crystals will get larger as granite are stored.