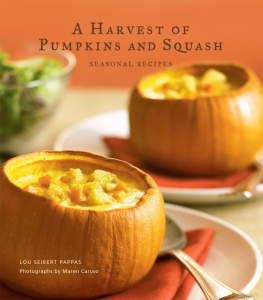

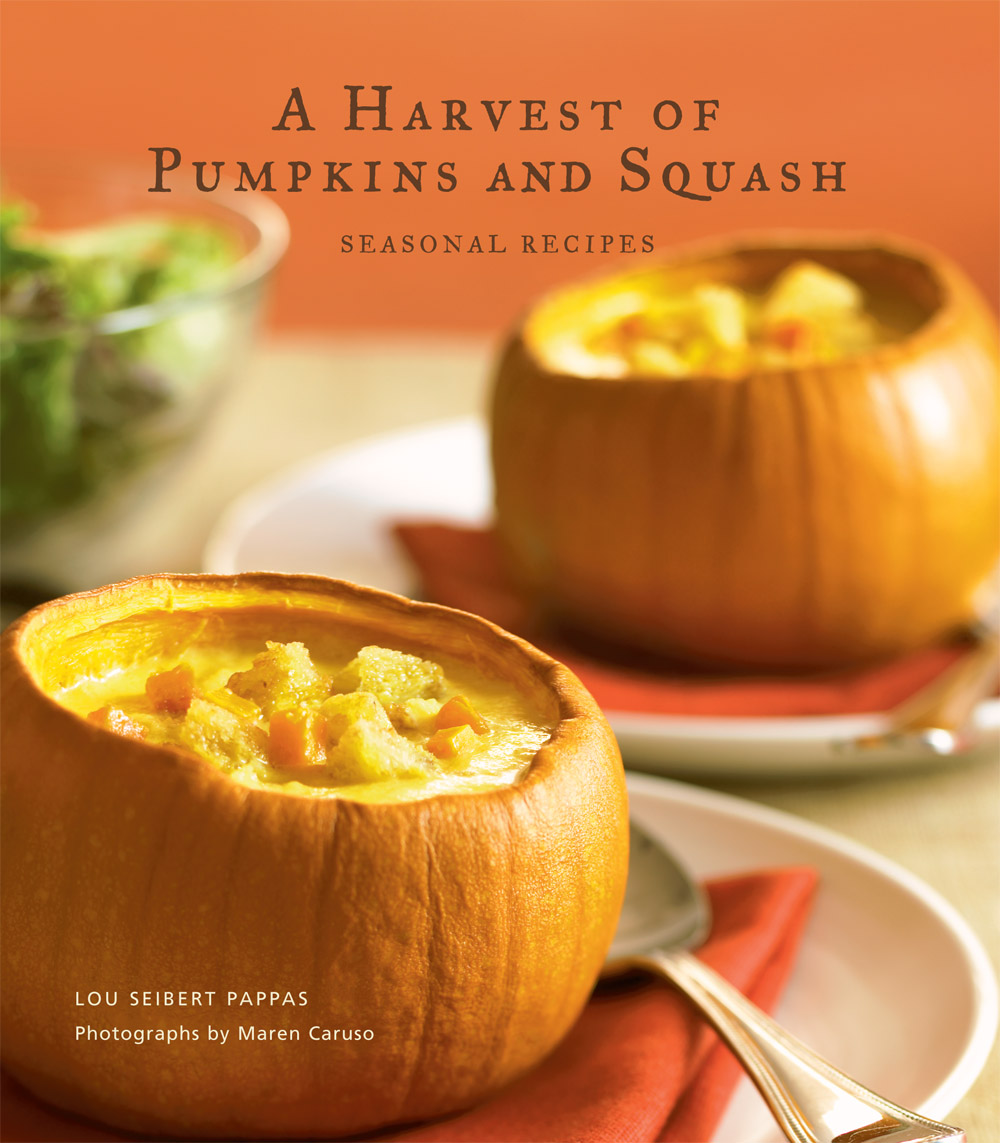

In its multitude of forms, squash perennially wins top honors as a versatile, delicious vegetableas well as a year-round staple. Both winter and summer squash varieties enhance a wealth of savory and sweet dishes. And in spite of its sometimes humble or even homely reputation, squash can be impressive, glamorous, and even fun: beautiful orange butternut squash cut into half-moons and roasted; perfect halves of acorn squash, with the dark green skin striking against the pale yellow flesh, drizzled with caramel; the chayote, hailing from southern climes, used for edible containers for a spicy Middle Eastern lamb stew; long, thin, elegant slices of summer squash making a bed for broiled fish; spaghetti squash baked and topped with a classic meat sauce as a nod to its soft, pastalike strands. Pumpkins, the star of so many porch stages in fall, can turn everyday fare into whimsical and dramatic presentationsa pumpkin soup tureen brimming with chicken soup or stuffed mini pumpkins welcomes diners to a table with a big smile.

For breakfast, lunch, dinner, and dessert, pumpkin and squash are rewarding players in dishes from delicate souffls to inviting, comfort-food bisques. The repertoire of recipes in this book encompasses delectable muffins, pizza, coffeecakes, and yeast breads; hearty main-course soups and some lighter ones for starters; salads and vegetable accompaniments; pasta and polenta; entres; and of course, the rich and nutty pies, gingery spice cakes, flan, crme brle, ice cream, and cookies that proliferate in fall and feature sweetly in our holiday traditions.

For centuries, pumpkins and squash have graced American hearths and homes. In more recent decades, abundant summer squash have been arguably more prominent, more familiarexcept for the hallowed pumpkinin both the marketplace and backyard gardens. But now, as the demand for locally grown produce and sustainable agriculture grows, savvy purveyors are expanding their bounty with heirloom varieties of both summer and winter squash, and our local greengrocers and farmers markets are flaunting a wealth of eye-catching squash and pumpkins leading up to the holiday season. New varieties in colorful hues and various shapes and sizes are prompting intrigue for more cooking and sampling.

Now is the perfect time to pick up some pumpkins and squash and enjoy their nourishing goodness for dining around the clock.

All squash are members of the gourd family known as Cucurbitaceae. Most squash belong to the genus Cucurbita, which subdivides into the tender-skinned summer squash and the hard-skinned winter squash.

Winter squash are allowed to ripen to maturity so their shell hardens to protect the interior. Some, like butternut and kabocha, are still easy to peel; others require a cleaver or even an ax to puncture the rind. Pumpkins in any size belong to the winter squash family. By contrast, summer squash are picked immature while the skin is tender and the flavor delicate and mild.

Winter squash played a major role on the American frontier. Pilgrims adopted the vegetable, replicating the planting and cooking techniques of Native Americans. They even hollowed pumpkins, stuffed them with apples and maple syrup, and baked them in the coals. Our forefathers valued squash as one of their favorite vegetables because of its excellent keeping quality. But while once regarded as a staple in root cellars, kitchens, and on dinner tables across the country, winter squash experienced a slump in popularity over the last several decades as fast food, trendier vegetables, and speedy cooking came into play.

Today, winter squash have come back into the spotlight, rejoining summer squash as beloved vegetables suitable for steaming, roasting, sauting, and pureing. Besides having deep flavor, the rich source of nutrientsin particular beta-caroteneis a key to the upswing in popularity for winter squash. Summer squash, nutritional champions in their own right, continue to be cherished in every season for their fresh flavors, speedy cooking, and tastiness in the raw state.

Winter Squash

There is a plethora of winter squash varieties, many of which are now standard features at produce markets. They differ greatly in size, shape, and exterior color, yet all have a sweet yellow or orange flesh. (That colorful flesh reflects the fact that most winter squash are a great source of vitamins and minerals. One of the most prevalent nutrients is beta-carotene, which has powerful antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Winter squash also contain vitamin C, potassium, dietary fiber, omega-3 fatty acids, and various B vitamins.) When selecting, look for squash with dull skins and a heavy feel. Lighter, shinier squash may not be fully ripe.

Winter squash are at their prime from September to February. Excellent keepers, they will stay fresh for up to six months if stored in a dry, dark place. Use as pretty centerpieces before cooking. Once cut, wrap in plastic and refrigerate.

Unlike summer squash, which are good to eat raw, winter squash must be cooked. Cooking tenderizes their fibers and turns them smooth and creamy. Home cooks are discovering how easy it is to microwave, bake, and roast winter squash. (Boiling and steaming tend to introduce more water into the squash and so they are less appealing cooking methods.)

As you cook with winter squash varieties, it is easy to develop favorites. Butternut rates high for all-around versatility in soups, pies, casseroles, and breads, with its rich, deep orange, fine-textured flesh. Kabocha and buttercup are not quite as sweet but are excellent, too. Acorn is a natural for baking and serving in the half-shell. More mild-flavored banana and Hubbard squash are ideal for serving as a side dish. Note, although most winter squash can be used interchangeably in recipes, spaghetti squash is an exception. It is more like a cross between a summer and winter variety; when cooked, the interior separates into pale golden filaments that are moist and tender like zucchiniand yes, like spaghetti!

The best pumpkins for cooking and baking are small to medium pie pumpkins such as Sugar, Sugar Pie, New England Pie, Baby Bear, or Triple Treat. Some of the newer ornamental white varieties, such as Lumina or Fairytale, are good both for decoration and eating. The pantry standby, canned pumpkin pure, is now widely available from many high-quality producers and is a fine choice for many dishes, as well as in a pinch. Winter squash pures are readily available as well.

To prepare winter squash for cooking, first rinse the squash. Cut it in half lengthwise or cut off a topknot if using the shell for a container. A cleaver is a useful tool on very hard rinds if halving; use a very sturdy knife to cut out tops. Scoop out the seeds and fibers and discard (unless you are going to toast the seeds). Cut large squash into serving size pieces.

The easiest method for cooking winter squash is baking it in a conventional oven or cooking it in a microwave oven. Place squash halves cut side down in a parchment paperlined baking dish and bake at 350 to 375F until tender when pierced with a knife, 50 minutes to 1 hour. Or, microwave in a covered dish with a tablespoon or two of water for 7 to 10 minutes per pound; let stand a few minutes to finish cooking.

Appliance experts recommend preheating an oven for 30 minutes before baking. This is especially important with newer ovens. It is smart to check your oven with a portable oven thermometer placed in the oven. The recipes in this book include doneness cues plus cooking time ranges.