SUSTAINABLE

MATERIALS

WITHOUT THE HOT AIR

SUSTAINABLE

MATERIALS

WITHOUT THE HOT AIR

Julian M Allwood

Jonathan M Cullen

with

Mark A Carruth, Daniel R Cooper, Martin McBrien, Rachel L Milford, Muiris C Moynihan, Alexandra CH Patel

Department of Engineering

University of Cambridge

UIT

CAMBRIDGE, ENGLAND

Preface

We dont talk enough about steel, cement, plastic, paper and aluminium, but without them wed be living in huts and walking to work, our shops would be empty, wed have to grow all our own food and wed have no medical care. We make these materials with amazing efficiency, yet they have the same impact on the environment as the whole of the worlds transport system. And that impact is growing, were likely to want twice as much material within 40 years. And if we do that, well reduce the chance that our children can live as well as we do.

Wed all like to take action to find a more sustainable futurebut what can we do? Can we put pressure on the materials industries to clean up their act? Not really, theyve largely done so already, and theyre so efficient that weve nearly reached the limits of whats possible. So it sounds as if were stuck, but thats where this book comes in. So far weve been looking at the problem with one eye open, hoping that industry can magically solve the problem. But with both eyes open we have a whole new set of options. Rather than making more materials, we could use them more wiselywith less material, keeping them for longer, reusing their parts and more. And these options make a huge difference: we really could set up our children with a more sustainable life, without compromising our own.

Weve spent three years looking at the realities of a sustainable materials future with both eyes open. Weve made hundreds of factory visits, held meetings and workshops spanning every aspect of the materials world, weve tried things out in our lab, and checked out our ideas with other scientists and people in the government. This book is the result: it tells the story of materials production, what we make and how we do it, whos involved and how we make money, and weve found out about every way we could do things differently from new processes to new products to new ways to use and value materials.

Weve written the book to share our optimistic view of the future: we can make a big difference if we look ahead with both eyes open. Weve written it for people who work with materialsmaking them, shaping them, or using themand people who influence how it happens. For policy makers and negotiators, financiers and accountants, people who assess risks or set standards, and for teachers, researchers and the students wholl define our future material world. Its written for people in industry and its for their customers. Because were all involved. We all depend on these five tremendous materials, we need to learn to use them in a different way, and we all have a say in the change. And the good news story in this book is that we can make a big changebut only if we look for it with both eyes open.

Contents

Prologue: Our Material Children

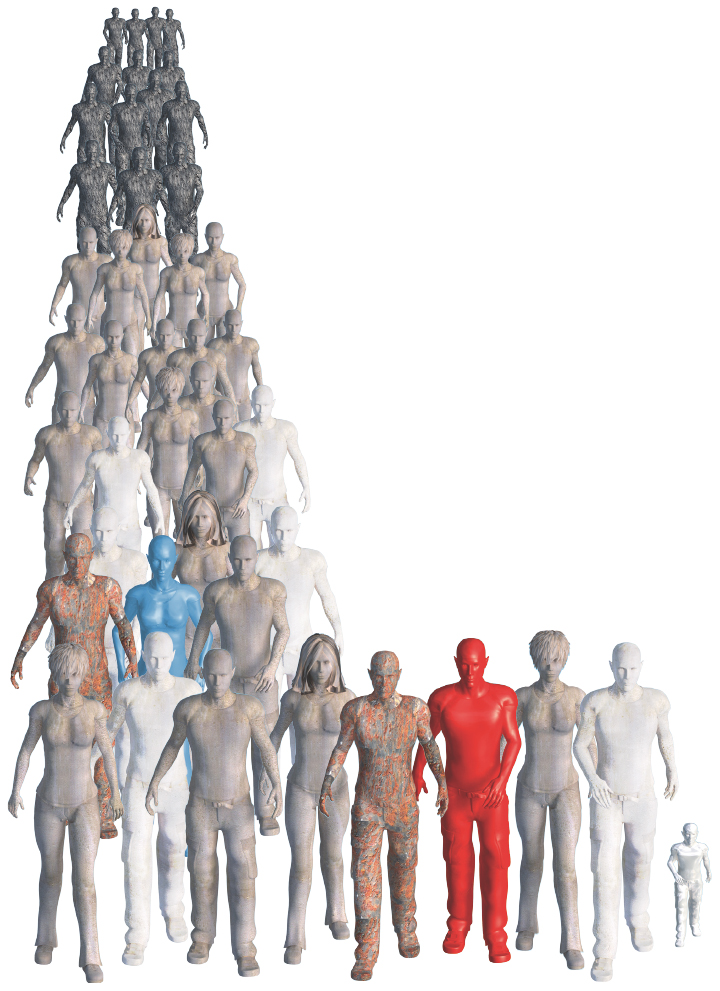

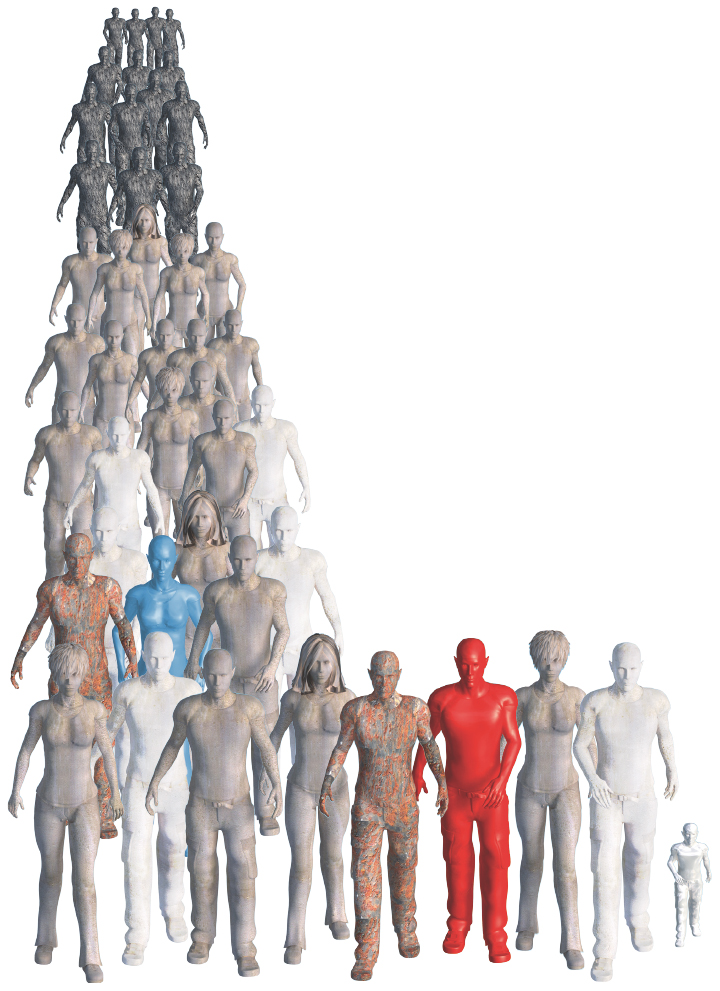

If we take the worlds annual production of steel and divide it by the worlds population, each one of us causes 200 kg of steel to be made each year. If we used this steel to make a sculpture, it would have the same volume as a life-size statue of an eight year old child. Following the same logic every year every one of us also gives birth to ten cement, one plastic and three paper eight-year olds, and one new-born aluminium baby.

These material children are largely hidden. We are anaesthetised to their birth, but it is environmentally painful. Converting natural resources into useful materials is energy-intensive, uses land and water, and releases emissions to air, water and soil. Using one measure only, creating our material children causes the release of around 1,000 kg of CO2 per year, the same as would be emitted by burning 400 kg of coal. And if we made sculptures with the coal, we would have three or four average sized men of coal.

On average, every person on the planet gives birth to these 16 material children and launches their 4 coal parents into the sky every year. But we arent all average. In the UK and other developed economies in Europe, America, Japan and parts of China, our annual consumption of materials is approximately four times the global average. So for us, the aluminium baby is now two, the rest of our material children have grown up and married, and they now have 14 coal parents.

The life-size procession of material adults marching down this page could be sculpted from the materials produced every year, for every person in the UK, and every one of us causes the 14 coal adults at the back to be launched into the sky, every year.

Acknowledgements

Every aspect of this book has involved collaboration, and we have enjoyed tremendous committed support and help from an enormous number of people. We would like to express our warm thanks to:

John Amoore, Karin Arnold, Prof. Mike Ashby, Prof. Shyam R. Asolekar, Roy Aspden, Efthymios Balomenos, Margarita Bambach, Mike Banfi, Prof. John Barrett, Chris Bayliss, Terry Benge, Marlen Bertram, Peter Birkinshaw, Manuel Birkle, Nancy Bocken, Paul Bradley, Mike Brammer, Nigel Brandon, Louis Brimacombe, Clare Broadbent, Emmanuelle Bruneteaux, Chris Burgoyne, David Calder, Simon Cardwell, Heather Carey, Jo Carris, Nick Champion, Andrea Charlson, Barry Clay, Nick Coleman, Grant Colquhoun, Richard Cooper, Steve Court, Polly Curtiss, AnaMaria Danila, John Davenport, Dr. Joseph Davidovits, Prof. Peter Davidson, Richard Dinnis, Prof. David Dornfeld, John Dowling, Kelly Driscoll, Dan Epstein, Jack Fellows, David Fidler, Kate Fletcher, Andrew Fraser, Steve Fricker, Prof. Mark Gallerneault, Rosa Garcia-Pineiro, JoseLuis Gazapo, Bernhard Gillner, Mark Gorgolewski, Staffan Grtz, Prof. Tom Graedel, Bill Grant, Christophe Gras, Allan Griffin, Ellen Grist, Simon Guest, Volkan Gley, Prof. Peter Guthrie, Tomas Gutierrez, Prof. Timothy Gutowski, Christian Hagelueken, Martin Halliwell, Peter Harrington, Judith Hazel, Kirsten Henson, Prof. Gerhard Hirt, Shaun Hobson, Peter Hodgson, Gerald Hohenbichler, Andy Howe, Richard Howells, Len Howlett, Tom Hulls, Roland Hunziker, Jay Jaiswal, Carl Johnson, Aled Jones, Tony Jones, Ulla Juntti, Sarah Kaethner, Andrew Kenny, Holly Knight, Peter Kuhn, Bob Lambrechts, David Leal, Rebecca Lees, Christian Leroy, Ma Linwei, Ming Liu, Peter Lord, Jim Lupton, Kelly Luterell, Prof. David MacKay, Roger Manser, Niall Mansfield, Fabian Marion, Graeme Marshall, Ian Maxwell, Alan McLelland, Hillary McOwat, Alan McRobie, Graham McShane, Christina Meskers, Prof. Cam Middleton, David Moore, Cillian Moynihan, Prof. Daniel Mller, Dr. Omer Music, Sid Nayar, Gunther Newcombe, Anna Nguyem, Duncan Nicholson, Adrian Noake, Sharon Nolan, George Oates, Mayoma Onwochei, Andy Orme, Yukiya Oyachi, Andrew Parker, David Parker, Alan Partridge, Mike Peirce, Matt Pumfrey, Philip Purnell, David Reay, Henk Reimink, Jan Reisener, Chris Romanowski, Mike Russell, Pradip Saha, Geoff Scamens, Thomas Schaden, Patrick Schrynmakers, Fran Sergent, Prof. Alan Short, Jim Simmons, Kevin Slattery, Emily Sloan, Derick Smart, Andrew Smith, Prof. Malcolm Smith, Martin Smith, Prof. Richard Smith, Zenaida Sobral Mourao, Greg Southall, Mick Steeper, Michael Stych, Judith Sykes, Katie Symons, Prof. Erman Tekkaya, NeeJoo The, Stefan Thielen, Katelyn Toth-Fejel, Micahel Trompeter, Robert Tucker, Hendrik vanOss, Tao Wang, Prof. Jeremy Watson, Andrew Weir, Anna Wenlock, Alex West, Glyn Wheeler, Gavin White, Mark White, Ollie Wildman, John Wilkinson, Larry Williams, Pete Winslow, Prof. Ernst Worrell, Masterchef Roseanna Xanthe, Lina Xie, Prof. Liping Xu, and to everyone else we should have named.