Contents

Guide

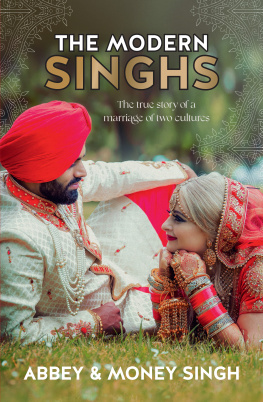

For our families and our subscribers

CONTENTS

MONEY

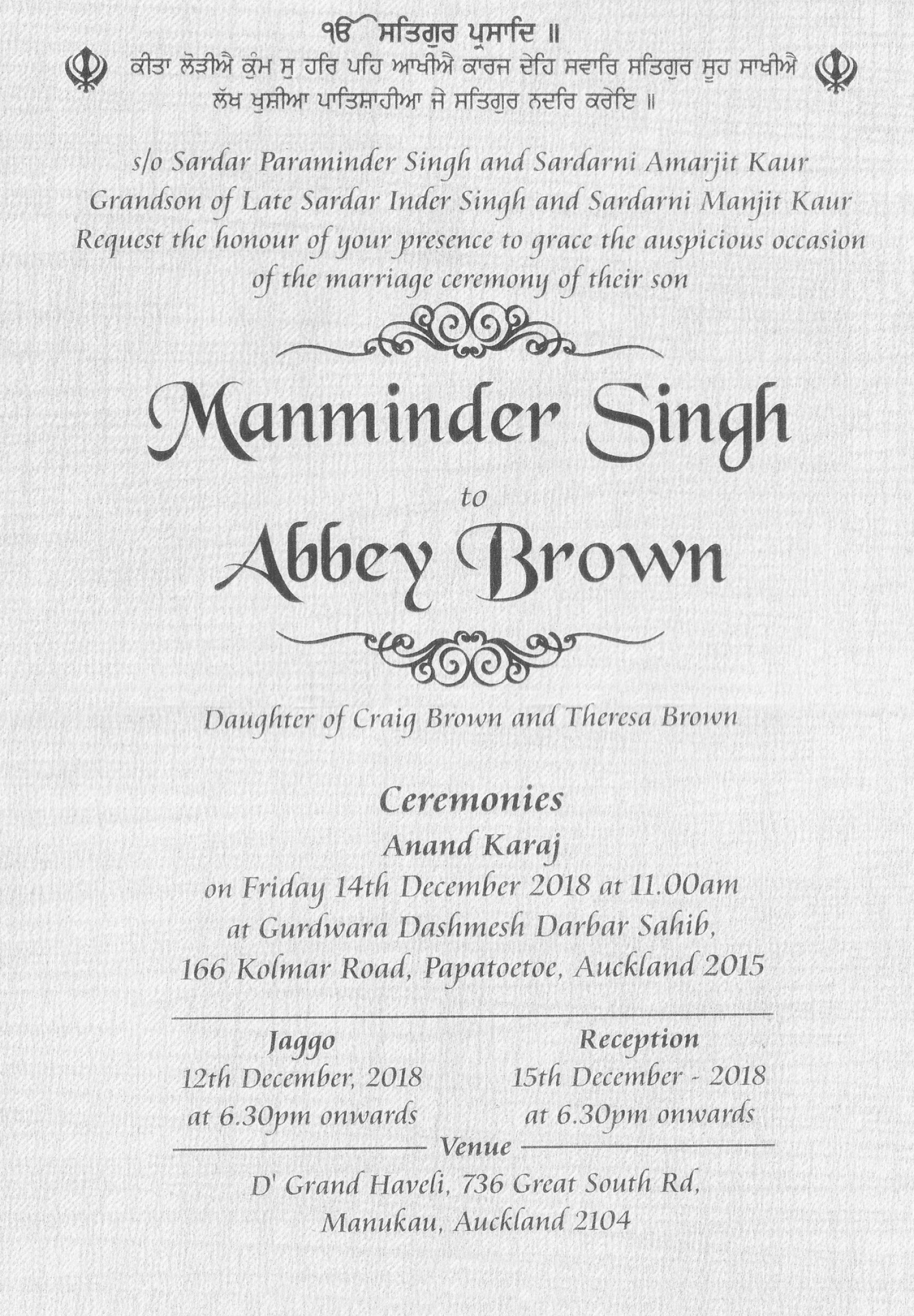

My parents are both from the Punjab area of northern India but from different backgrounds. My fathers name is Parminder (his family nickname is Pindi) and he is from a small village called Bowani. My mother, Amarjeet Kaur, is from the nearby city of Ludhiana. Amar means pure. In New Zealand, everyone calls her Pam; she chose this name as its an acronym, made up of Parminder, Amarjeet and Money she said it was a reminder of all three of us. The cool thing is that now, many years later, Mum says the A is also for Arshdeep, my younger brother, and for Abbey, her daughter-in-law, so Pam is a very special name for her.

Mum and Dad had an arranged marriage, which is the traditional way in India. My father is the eldest of five siblings, all of whom had arranged marriages apart from his brother Sukhminder. It was common to get married around seventeen or eighteen, although, in their case, Mum was nineteen and Dad was twenty-five. Many of the traditions are changing these days and, with each new generation, the rules relax and things are more flexible. But, back then, it was imperative that the females in the family get married as soon as possible because the girls family was required to provide a dowry, which could be expensive and a source of pressure. In an arranged marriage, it is not as much about two people falling in love, as it is about two families joining together. When someone is at the age that they should marry, word travels through the extended family: My daughter needs a husband or I am looking for a wife for my son. Can you recommend anyone? With little access to phones and computers, this was usually done by word of mouth or letters sent by post and, gradually, the message would be passed to more and more people until, eventually, something about a situation or a potential partner would catch the familys attention.

For my parents, there wasnt any dating and no time for romance. Dad was working long hours in a tailors premises in the town of Doraha, his wages helping to keep the family afloat. A life of socialising was completely out of the question, and girls were not really on his radar. My mothers family were interested in the arrangement because my fathers father was well respected in our village. Mums older sister, who had been like a surrogate mother to her when she was younger, had already married and moved into her husbands familys home, and there were a younger and older brother still at home, but it was time for my mother to get married and start her own life.

My parents had never met before the day they got engaged in the Gurdwara (a Sikh temple). Prior to then, they had only seen a photo of one another. This first meeting is important; it is a promise of their bond before God. They married a year after their engagement and had met only two times further during this time: once for a Lohri party for a family member, and again at a small engagement party.

I see my parents relationship as a love story even more because they had to learn to love each other rather than fall in love first. Mum said that when she saw my father she was happy. She said he had a fine beard and nicely tied turban, and she felt very lucky to be arranged to this handsome man. My dad said she was the most beautiful woman he had seen and he was excited to be her husband and spend their lives together.

Some village people are well off and own land that they lease to farmers, but Dads family was poor. Everyone lived together, my uncles and aunties, my grandmother and grandfather, my great-grandmother. When she got married, Mum moved in and became part of this extended family. She fell pregnant within a few months of being married so it was a lot for her, coming to terms with her first pregnancy, settling in, and because she was now responsible for everything, she took care of the house, did the chores and cooked the meals. It was a real adjustment and she was so busy. She got along really well with my fathers parents and quickly became very close to them, which helped her. Everyone was so excited there was going to be a baby.

I was born in Ludhiana Hospital on 13 August 1993. Dad had stayed behind to work when Mum left to give birth, and there was no phone to find out how things were going, but one of our family friends happened to be at the hospital and cycled the 25 kilometres to the village to bring the news that Mum had had a baby boy. Again, things have changed since then, but to have a boy was a big deal at that time as it meant less financial pressure on a family. When I was born they named me Manminder. Mani is the most common nickname to this, but early on, my grandfather started calling me Money and this has been what everybody has called me since.

It is probably difficult for many New Zealanders to imagine the kind of lifestyle I was brought up in and how I spent my first four years before we moved to New Zealand. Even though it was not the most extreme poverty that you find in India, my parents had to work hard to survive. In the city of Ludhiana, Mums family had gas cylinders and stoves to do their cooking inside the house, but there was none of that in Bowani. To prepare a meal, my mother would first have to make a fire. Every morning, the women went to a farm and collected cowpats, which were brought home and stored to dry out. She would use these to light a fire under a handmade clay stove, out in the garden.

All daily activities were physical tasks. My family couldnt afford to buy milk, but they had a cow at home that Mum milked each morning. The house was just a concrete shell, divided into a few rooms, with no real bathroom or toilet. The windows didnt have glass: the house was boiling hot in summer and freezing cold in winter. There was no plumbing we didnt have hot water coming out of a tap. Water was pumped from a well and carried home, then a fire was lit to boil it, either for drinking, because it wasnt safe to drink otherwise, or for bathing. Once it was warm, wed use a scoop to wash ourselves. I remember I couldnt be bothered doing that after a while and just washed myself with cold water. There was no sit-down toilet. You learnt to squat over a hole in the floor. And with no cistern or flush switch, you tipped in another bucket of water to wash everything away. We didnt use toilet paper because it was too expensive. Once again, the tap and bucket were used.

If you were in a car, this meant you were displaying wealth. In India, you see the poorest and the richest of society, but being wealthy there doesnt mean Lamborghini rich; it means Honda Civic rich. When I was very small, Dad had a motorbike that the three of us would ride on, me standing between Dads legs, holding onto the handle bars, and Mum on the back. That was our only transportation.

If you have to spend your whole day fetching water and making fire for the most basic of tasks, you will never get ahead because you just dont have the time. That is the economics of it. This was the life I led. I didnt know any other way. Some time later when we took my little brother, who was born in New Zealand, to India, we simply bought him bottled water. Things had changed a lot in just a short time. I think its important for people to know that the hand-to-mouth existence is only one generation ago. The people who were milking a cow every day in India could well be the same people who now buy their milk from a corner dairy in New Zealand.

Next page