Table of Contents

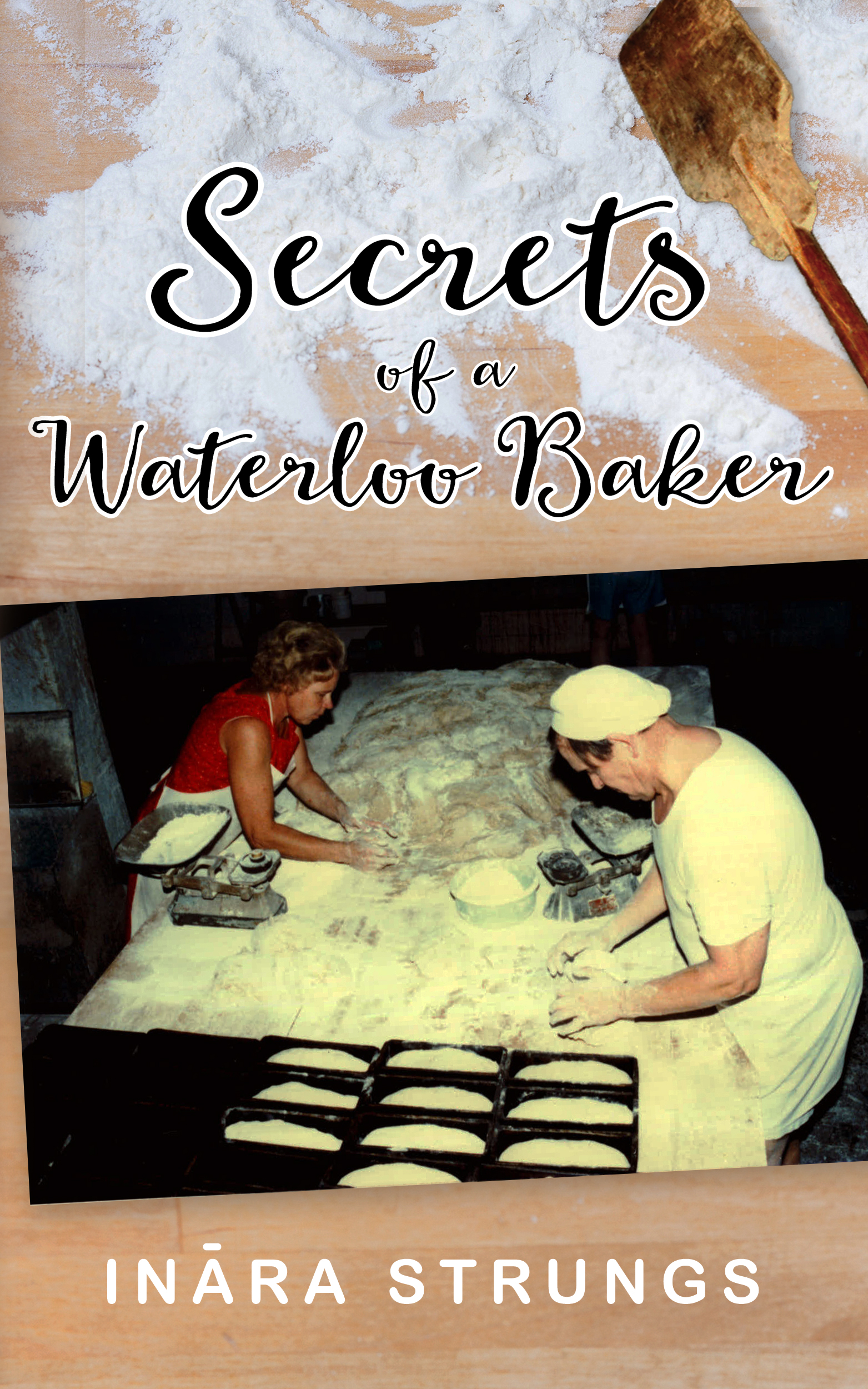

SECRETS OF A WATERLOO BAKER

Inra Strungs

This is an IndieMosh book

brought to you by MoshPit Publishing

an imprint of Moshers Business Support Pty Ltd

PO BOX 147

Hazelbrook NSW 2779

http://www.indiemosh.com.au/

Copyright 2016 Inra Strungs

All rights reserved

Illustrated by Linda McInally

Photographs supplied by Aivars tubis,

Oskars tubis and Anita Apinis-Herman

Licence Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If youre reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to your favourite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the author and publisher.

To my parents,

Lga and Pteris Strungs,

bakers extraordinaire.

Kvieu maize, griu maize,

T pa ciemu lenderja;

Rudzu maize, mieu maize,

T saimtes turtja.

(Latvian folksong)

[White bread and buckwheat bread

Just loaf around;

But rye bread and barley bread

Feed the people.]

INTRODUCTION

Every food worth eating has a secret recipe, says my friend as we tuck into a delicious risotto in a restaurant in Danks St, Waterloo.

Exactly, and why would you give it away to the opposition? I reply. We agree that there is something in the risotto that definitely isnt in the list of ingredients and which the chef wouldnt divulge.

I am in Sydney visiting family and am having lunch with an old schoolfriend. Though I was born in Sydney and lived there for 21 years, I still like to be a tourist when I come to visit from Brisbane, where I now live. Hence I thought it would be interesting to check out Danks St with its trendy restaurants and galleries. It is an interesting mix of old warehouses and factories, modern units and street cafes, with palm trees and sports cars lining the road.

We sit drinking our long blacks after the meal and discuss the change in the area since wed attended the nearby Sydney Girls High School. Waterloo has gone the way of many inner city suburbsoriginally industrial or slums but now redeveloped as highly desirable areas to live. They are close to the city, the beaches and other facilities, and have good transport and a sense of history.

Then my friend says, Talking about secret recipes, your family must have had a few.

Ive also just been thinking about my family. They had a small business, called Elma Bakery, several blocks away from Danks St. Id lived there with them in the 1970s and continued to visit the bakery until the 1990s.

I think of the delicious smell of baking bread, a hot, moist, slightly sour smell that stimulated the taste buds and always pervaded the bakery and our living quarters, and of the way the bread was baked.

Yes, I say to my friend after a pause, there were secret recipes. No one wanted them after the bakery was demolished in 1991, but I bet there are people today who wouldnt mind having them.

Exactly, all those passionate home bakers and those who are obsessed with cooking shows or with natural food. You should record the way it was baked before its too late. Do you know the secret recipe?

No. Not really.

Well, go and find out. You always said you had hundreds of happy customers who couldnt find any other bread like it.

I decide to take a journey into the past to uncover the secret art of black bread (and sweet-and-sour) in Waterloo.

1

BREAD, BEAUTIFUL BREAD

I go home to my parents place in Arncliffe, where Im staying while in Sydney, and think about Elma Bakery. My mother and I have a few glasses of wine, and my father whisky, as we discuss the bread. They offer me some black bread theyve bought and say, Its not too bad. Every bread is measured against the bread they used to bake.

I lie in bed afterwards, considering what the secret of the breads excellence and success really was. I try to consider it in a logical way and go through various factors.

Was it the place, Waterloo, where it was baked? In other words, was it the effect of the environment or the terroir, to use a viticultural analogy? Was Waterloo a place where migrant food thrived, like Dixon St in Sydney or Acland St, Melbourne? Was it the long history of Waterloo, one of the oldest suburbs in Sydney? Or did the bakers and their Estonian and Latvian heritage hold the secret to the bread? Or was it, I hear you ask, the actual recipe, which Ill have to get hold of.

Before I explore these factors, I think about Elma bread and research breads in general and what the current state of play is in this field. Its such a basic part of life and seems so commonplace, yet there is much ferment in breadmaking. There are various movements promoting changes in breadmaking, even bread wars. There is a powerful artisan bread movement and linked to this, methods devised to judge or appreciate bread. This has all become more prominent in the twenty-five years since Elma Bakery closed its doors.

The types of bread baked at Elma Bakery were mainly black bread and sweet-and-sour. I remember eating it warm, just out of the oven, with butter or peanut butter melting over its spongy surface, and savouring the aromatic, crusty taste. They were dense breads made of varying proportions of wheat and rye flour and didnt look like conventional Australian white bread. In some ways they were an acquired taste, or bread you had to grow up with to appreciate. Hence it was eagerly sought by European migrants, particularly Latvians and other Balts. More recently, it has become more popular with the general population when artisan baking has come to the fore. In earlier years Elma Bakery also produced a health bread and a fruit bread. The fruit bread was more to Australian tastes and I used to sell it to my friends at school.

Of course, bread overall has a very rich history. Some type of bread is a staple of the diet of many cultures in the world, whether white bread, brioche, pumpernickel, rice bread, naan, lavash, damper or another of the thousands of breads available. Bread is as old as it is ubiquitous. There is evidence prehistoric humans may have eaten a type of bread at least 30,000 years ago in Europe, since starch grains, possibly from ferns or cattails, have been found on grinding stones. From the Neolithic Age 10,000 years ago, grains became the mainstay of making bread.

Not surprisingly, bread, breadmaking and ovens are part of the culture and folklore of many ethnic groups. In some peasant mythologies, the rising of dough is associated with the rising and nurturing powers of the sun, and the oven, already womblike in form, is a fertility symbol and has magic dimensions in that it can transform food from a raw to cooked state. There are many metaphors involving the concept of bread, for example, as a synonym for the basic necessities of life. Bread also figures in religious ceremonies such as the Christian Eucharist. Bread is important in Latvian culture, from where my family originated, but more of that later.