Note

The author and publisher have made every effort to contact copyright holders of images; any omissions will be rectified on reprints or new editions upon notification to the publisher.

Contents

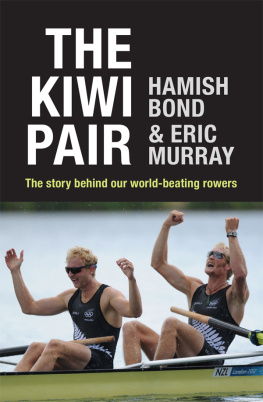

Look at New Zealand sport and it is hard at times to see past the wall-to-wall media attention afforded rugby, cricket, rugby league and, increasingly, netball. Soccer, by virtue of the All Whites and the Wellington Phoenix, has been revelling in a greatly increased public profile, motor racing has made gains, and basketball has benefited from the Breakers. For most other sports its a case of beavering away, invariably out of the spotlight, and trying to maximise whatever media opportunities are forthcoming. Rowing tends to fit into that category. It shouldnt. Rowing New Zealand has a history rich in international accomplishments. Since first winning an Olympic final in Mexico in 1968 it has deserved a higher profile, and the advances it has made place it pretty well at the top of the countrys Olympic sports when we assess our medal prospects for London in 2012. In 2009 it had eight crews ranked in the worlds top eight, the strongest position held by New Zealand in any of the Games sports and that was without including world champion lightweight single sculler Duncan Grant, whose event is not on the Olympic programme. Without fuss, and with little fanfare, there has been an acceleration of achievement, including the claiming of 15 world championships and three Olympic gold medals in the decade to the end of 2009. No other mainstream sport in New Zealand can match that, yet rowing generally has to wait till the Olympic Games come around to receive the attention it deserves. In the 200506 season it introduced a programme designed to produce champions with greater consistency through its four regional performance centres, with the backing of Sport & Recreation New Zealand (SPARC), which regards what rowing has created as very much a model for other sports.

This book is not a history of rowing. Rather, it is more an attempt to look at the personalities the athletes, coaches and administrators and events and achievements that have shaped the sport in this country and, on occasions, captured the publics imagination. It is also an opportunity to provide some insight into what has made New Zealand such a rowing power, able to match the worlds big nations despite having relatively few lite competitors. Until recent years this was achieved on a shoestring budget by a group of dedicated volunteers, some of whom are overtly dynamic figures. Perhaps there is no better example of this than Don Rowlands, who was chairman of the organising committee at the first world championships at Lake Karapiro in 1978, and even though he was well into his eighties, was named patron of the 2010 event.

Rowlands, an outstanding businessman as well as a champion rower, aimed high. Two other men shared his dream fellow national selectors, coach Rusty Robertson and Fred Strachan. The trio forced the big northern hemisphere countries to take seriously a little country at the bottom of the world, never more so than when they masterminded the eights win in the Olympic final at Munich in 1972. That result had a considerable bearing on the choice of Lake Karapiro to host the world championships six years later, and made such an impact in New Zealand that the benefits continued for many more years, even when the sport became professional and the concentration moved from big boats to small. Richard Tonks and Athol Earl, national selectors during the highly successful first decade of the 21st century, both won medals in 1972, and the methods of Tonks, arguably New Zealands best rowing coach, date back to what he learned from Robertson.

Rowing might well be the most gruelling of sports, although making comparisons is fraught with difficulty. However, double world champion Hamish Bond provided some insight after he competed in an event in another sport considered similarly tough cycling. He completed the week-long Tour of Southland in November 2009 and said that, while unable to give a totally definitive answer, the week of racing knocked his legs about and he found the crosswinds hideous. However, rowing taxed his whole body, leaving him sore and shattered. He imagined cyclings time trial event would be a closer comparison. During my research for this book, the most constantly recurring theme was the mentally and physically demanding nature of rowing training. I became aware, too, that in the professional era training tended to leave the athletes able to do little more than eat and sleep, and the huge volume of work increased the prospect of horrible rib stress fractures, something not previously a concern. It also required rowers to put their lives on hold, raising the question of whether the chance to win world or Olympic titles was worth all the effort and sacrifice. Certainly there is little that is glamorous about rowing; there are only occasionally any adoring fans following the athletes and, until comparatively recently, there was insufficient money involved for it to be a full-time pursuit. For all that, the many I spoke to were consumed by wanting to stand on the victory dais, no matter how fleeting the moment, and they were prepared to put themselves through daily floggings going backwards in a boat in order to make it possible. For some, training had to be fitted around full-time jobs and family life. I developed a deep admiration for what the rowers were prepared to endure to wear the black singlet.

A coach once said, Rowing wont kill you. Youll go unconscious before you die. Add to that the following comment from Olympic single sculling champion Sonia Waddell: Its just will. The last part of the race youre entirely brainwashing yourself. Your bodys in so much pain you just think of the things you can control and block out the things you cant. To me, these two statements encapsulate everything that rowers need to put themselves through in pursuit of the ultimate prize victory.

Im indebted to the many who so willingly gave of their time to be interviewed, and loaned me photographs. The results, in most cases, are very evident in the book. In the end, though, I gathered far more information than I could use. I would also like to thank, at Rowing New Zealand, Kevin Strickland and Richard Gee (the latter for allowing me to use so many of its images), the associations statistician Evan McCalman, and publishers HarperCollins for believing in the project.

1

Mahs first world title, and beyond

T he year 2005 was a hell of a year for Mah Drysdale. First, the rowing selectors denied him the opportunity to trial for the singles seat in the New Zealand team. He was only included after he appealed, but, having been chosen, he was hit by a fizz boat in training and suffered injuries so serious that his world championship aspirations looked to be in tatters. Having made a remarkable, and surprisingly quick, recovery he then suffered enormously under the training regime of his new coach, Richard Tonks. He described 2005 as the toughest year of my life, yet in early September in Gifu, Japan, he became the world champion.

Mah Drysdale has a smile for his supporters soon after crossing the line first in the world singles final of 2005 in Japan. Photo: Rowing New Zealand

Following the 2004 Athens Olympics, Drysdale knew hed had enough of competing in the New Zealand straight four. In three years his best result had been fifth in the Athens final, and he didnt fancy another four years building towards Beijing, in what he regarded as a largely uncompetitive crew. Drysdale had won the national singles title in 2003, and after Athens he decided that his future lay in that event. To give himself every chance of developing the necessary technique to compete internationally, and to convince the national selectors he was serious about the singles, he spent much of the 200405 New Zealand summer at his own expense at the highly regarded Tideway Scullers School on the River Thames in London. There he was coached by Bill Barry, a silver medallist for Great Britain in the coxless fours at the Tokyo Olympics of 1964 and related to Ernst Barry, a former world professional sculling champion. In August 1910, Ernst unsuccessfully challenged New Zealander Richard Arnst for the world title on the Zambesi River in what was Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia). Two years later, Ernst had his revenge, beating Richard on the Thames.