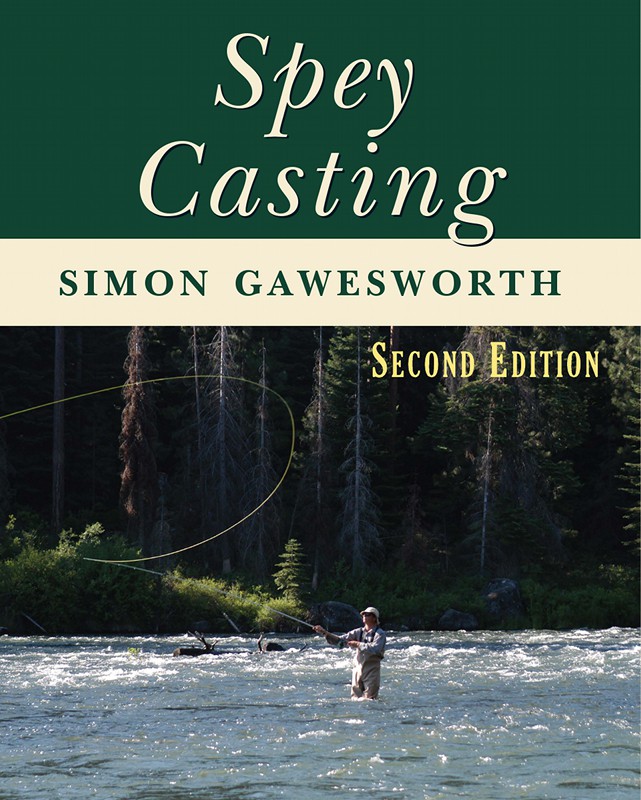

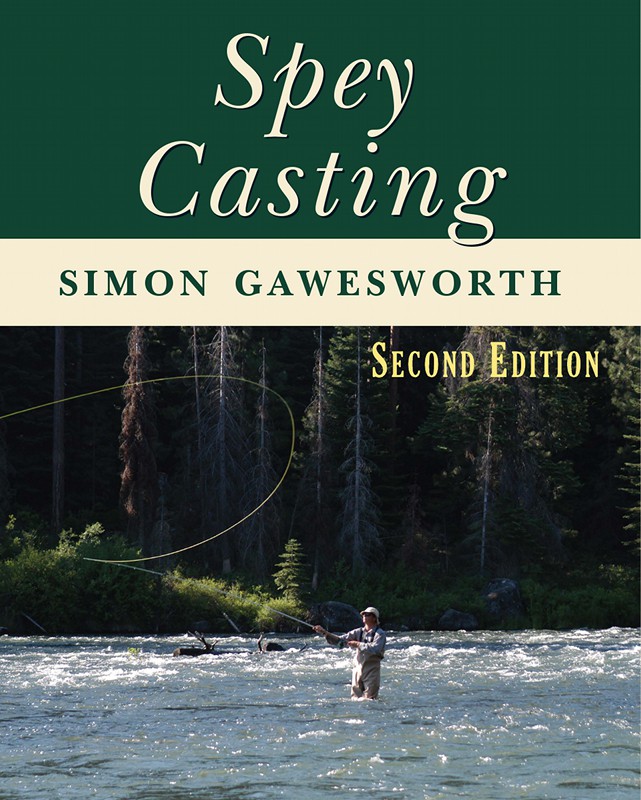

Spay Casting

Dean River Afternoon by Greg Pearson

Spey

Casting

Second Edition

SIMON GAWESWORTH

STACKPOLE

BOOKS

Copyright 2004, 2007 by Stackpole Books

Published by

STACKPOLE BOOKS

5067 Ritter Road

Mechanicsburg, PA 17055

www.stackpolebooks.com

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to Stackpole Books, 5067 Ritter Road, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania 17055.

Second edition

Photographs by Scott Nelson

Illustrations by Greg Pearson

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data for the Print Edition

Spey casting / Simon Gawesworth. 2nd ed.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8117-0268-3 (hc)

ISBN-10: 0-8117-0268-5 (hc)

1. Spey casting. 2. Fly casting. I. Title.

SH454.25.G38 2007

799.124dc22

2007001792

eBook ISBN: 978-0-8117-4931-2

QED stands for Quality, Excellence and Design. The QED seal of approval shown here verifies that this eBook has passed a rigorous quality assurance process and will render well in most eBook reading platforms.

For more information please click here.

For my dadmy mentor

For the noble Salmonmy respect

For Susan, Chloe, and Tristanmy universe

FOREWORD

T here was a time not so long ago when North Americans saw the double-handed rods used by Europeans as an unfailing sign of their backwardness, their lack of evolution as anglers. The view was that the single-handed rod was so much less work, especially with the new materials available, that to go on with the double-hander was ignorant. Lee Wulff spoke for us all when he stated, Rods over twelve-and-a-half feet are becoming relics now, used for sentiment. This view even affected the practice of Europeans who took up single-handed rods on their salmon rivers in surprising numbers. Then, not much more than a decade ago, the double-handed rod emerged from the shadows, this time with a vengeance. On both sides of the Atlantic, anglers were cutting up and splicing perfectly good lines to find more efficient alternatives to the usual double tapers, and the two-handed rod came to be known, to the dismay of its inventors, as the spey rod. What brought this on? First, anglers discovered that for covering moving water, the double-handed rod is much less work than the single-hander. The mingling of practices may well have occurred on the new anadromous fisheries in far-flung parts of the world like the Kola Peninsula of Russia and Tierra del Fuego. Here, with big rivers and big fish, the single-handers could look upon the two-handers, shoulder to shoulder, and see their advantages. (I remember arriving at the Ponoi River in Russia, the highest volume salmon river in the world, and being told by the guides that the Brits with the double-handers were rather dominating things.) While the single-hander is laboriously stripping running line back to the head of his shooting taper, the double hander has moved downstream, cast again, and resumed fishing in less time than it takes to tell it. Anyone fishing a single-handed rod down a long run behind a competent spey caster experiences the steady pulling away of his companion until the time comes when, having fished through, the spey caster is pulling up behind him. Where water coverage matters, spey casting offers real advantages in catching fish; where fish are pooled up as with some chinook fishing, it probably makes little difference, and its usefulness in still water remains to be seen. Today, efficient water coverage in rivers can be paramount. In very cold conditions, the spey caster avoids the cold, blue hands that accompany constant line handling. Finally, in fishing big rivers for big fish, bites can be few and far between; it cant hurt that the complexity and beauty of spey casting produces pleasure in itself or that the learning never quite comes to an end.

Without a doubt, the rediscovery of the two-handed rod took on all the appearances of a fad, with explanatory article after explanatory article appearing in the angling press, websites launched, and chat rooms inaugurated. English, Scandinavian, and North American positions about proper casting hardened. Rod and line designs arose and disappeared with astounding speed. Americans, late on the scene, brought such technical acuity to the tackle that in a short time American rods were the commonest around the world. Ten-year-old graphite two-handers became the subject of nostalgia. As ever, agreement on proper actions is hard to find, thus multiplying niches for rod builders. But much has been purposeful, and we may be approaching a tackle plateau, where the only real remaining breakthrough lies in price lowering in the wake of diminished research and development.

Throughout this period, various authorities have appeared on the scene, giving clinics, advising manufacturers, and writing books. Some good came from all of them, but for the end-user, the fisherman, it seemed a Babel of warring voices. The time had arrived for the definitive book on spey casting. This is it.

Simon Gawesworth brings an extraordinary amount of benefits to the task, perhaps least of which is that he is a champion tournament caster. He is a widely experienced angler with remarkably few prejudices about the quarry. From the tiny trout of Normandy to the Atlantic salmon of Russia, to the bounty of American public waters, Gawesworth has found unjaded pleasure in the original rewards of angling. He has studied the physics of spey casting with an eye to removing the voodoo that confuses students and subjected his theory to practice in innumerable casting schools. He owns a patient amiability, which, combined with extraordinary powers of observation, enables him to instruct clearly without enlarging the learners inhibitions. He has avoided the zealotry of a particular school of casting and, for someone of such long experience, is remarkably free of fixed ideas. The new casts that have resulted from the resurgence of two-handed rodssometimes in fisheries where they were previously unknownare enthusiastically examined by Gawesworth. He has a capacity for encouragement, clear explanation, humorous and helpful analogies, homilies, and witticismsall with the purpose of teaching and improving spey casting. While his goal is to get the spey caster up and running and back to his river, he is well aware that the refinements and aesthetics of this activity can contribute to pleasure in angling.

It is our good fortune that he writes as well and as clearly as he does: No one else could have done it.

Thomas McGuane

McLeod, Montana

December 2003

INTRODUCTION

S pey casting is a fly-casting technique that developed in Scotland in the mid-1800s, probably on the river Speyone of Scotlands premier salmon rivers. What is peculiar about spey casting is that it is a form of casting that has no backcast as such. When you see the river Spey, you will understand why this style of casting evolved on such a river. The Spey is a wide, powerful river. It is too fast to be able to wade out far enough to make space for an overhead cast and rarely are there nice gravel bars on which you can fish from. Also, the banks are lined with trees that run right down to the rivers edge. All in all this is a river that needs spey casting to be able to catch the Atlantic salmon that run there.

Next page