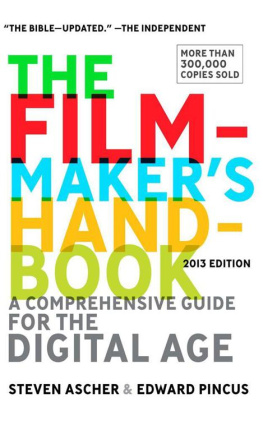

3-DIY

Stereoscopic Moviemaking on an Indie Budget

Ray Zone

225 Wyman Street, Waltham, MA 02451, USA

The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford, OX5 1GB, UK

2012 Ray Zone. Published by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher's permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein).

Notices

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of product liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zone, Ray.

3-DIY : stereoscopic moviemaking on an indie budget / Ray Zone.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-240-81707-1

1. 3-D filmsAmateurs' manuals. 2. CinematographyAmateurs' manuals. 3. Three-dimensional display systemsAmateurs' manuals. 4. Cinematographers. I. Title. II. Title: Three D.I.Y.

TR854.Z665 2012

777'.8dc23

2011044766

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-0-240-81707-1

For information on all Focal Press publications

visit our website at www.elsevierdirect.com

12 13 14 15 16 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in China

Acknowledgments

This book belongs to the 3D filmmakers whose work is addressed herein. I am in debt to my crew of stereoscopic cinema co-conspirators, especially California John Hart, Tom Koester, Eric Kurland, and the steadfast Lawrence Kaufman and his smiling beacon Cassie. Stephen Gibson and Arnold Herr have always added great depths of joy to my 3D book and filmmaking endeavors, for which I am very grateful. And my two partners in 3D movie crime, Jeff Amaral and Sean Isroelit, persist in delighting me with their support. Very special thanks to my son, Jimmy Ray Zone, for some all-important frame grabs in Chapter 19. Shannon Benna has been my rock as 1st AD, and I continue to laugh about 3D movies with Dave Gregory, and only sometimes at the expense of John R. Christopher, who I have to admit has brought his own brand of passion to this whole 3-DIY adventure.

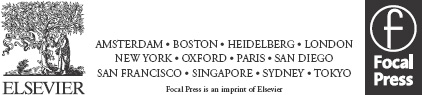

About the Author

Ray Zone is an award-winning 3D artist, speaker, and film producer who has produced or published 150 3D comic books featuring characters such as Batman, the X-Men, and the Simpsons. He is the 3D producer of Brijes 3D (2010), the first animated 3D feature film made in Mexico, and is the author of 3D Filmmakers: Conversations with Creators of Stereoscopic Motion Pictures (Scarecrow Press, 2005) and Stereoscopic Cinema and the Origins of 3-D Film, 18381952 (University Press of Kentucky, 2007). Ray's website in anaglyphic 3D! is www.ray3dzone.com.

Photo by Fernando Escovar.

Introduction: Do-It-Yourself 3D Movies

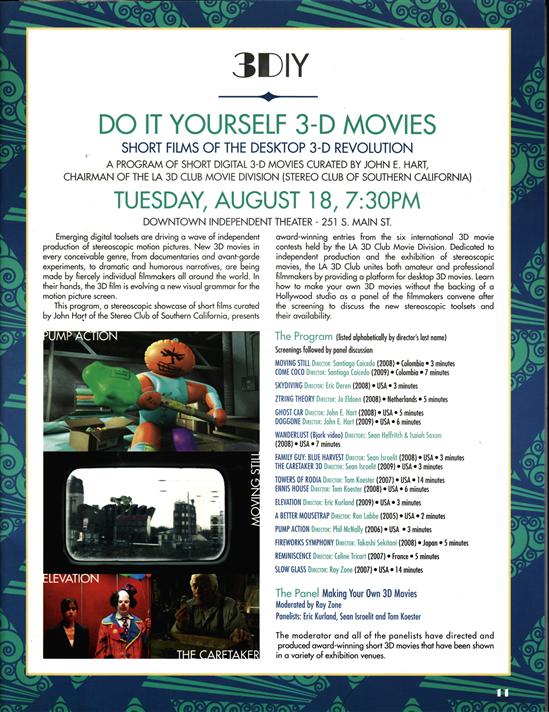

Figure A.1

Emerging digital toolsets are driving a wave of independent production of stereoscopic motion pictures. New 3D movies in every conceivable genre, from documentaries and avant-garde experiments to dramatic and humorous narratives, are being made by fiercely individual filmmakers all around the world. In their hands, the 3D film is evolving a new visual grammar for the motion picture screen.

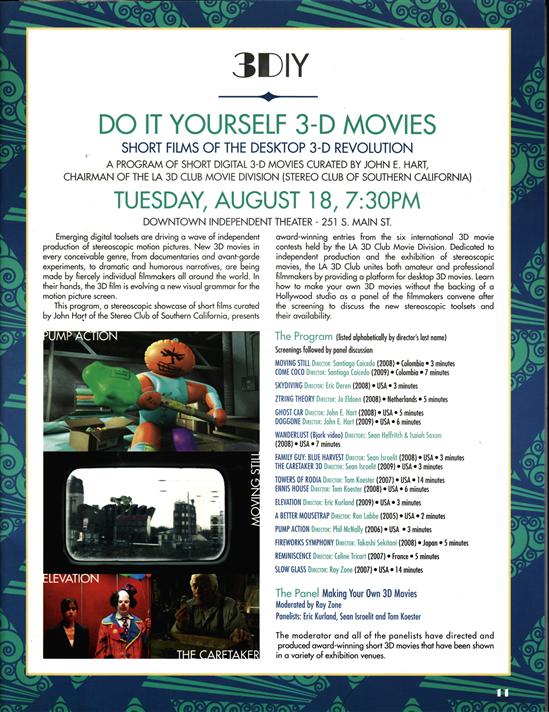

On August 18, 2009, a stereoscopic showcase of short films was presented by the LA 3D Club at the Downtown Independent Theater in conjunction with the Downtown Film Festival of Los Angeles. The program was a stereoscopic showcase of short 3D motion pictures that had been curated by John Hart of the Stereo Club of Southern California; it featured award-winning entries from the six international 3D movie contests that had been held by the LA 3D Club Movie Division.

In this book, the makers of most of those 3D films talk about the toolsets they used to make them and their motivations for doing so. There are additional 3D filmmakers and inventors included who also display or discuss a wide array of strategies and tools for independent stereoscopic moviemaking. The 3D productions themselves run the gamut from film to digital and live action to CG or a mix of many elements. The primary consideration for inclusion in the book was actual production, from start to finish, of an original work as a 3D movie. Though a great variety of both old and new 3D filmmaking tools are discussed, what doesn't change in the process are the fundamental parameters for stereoscopic imaging and display. By examining the unique tools and strategies of these 3D filmmakers, it becomes evident that all of them are dealing with the fundamental challenge of creating what Lenny Lipton has called the binocular symmetries of stereoscopic cinema, which means creating two movies that are different only in respect to horizontal disparity. This concept will be discussed in greater detail later in the book.

Home movie machinery came into the home as early as 1897 in Great Britain, and still stereophotography had become a relatively popular practice by that time. In 1923, Kodak introduced their 16mm Cine-Kodak camera and projector, tripod, and screen at a price of $335. 3D moviemaking in the home, however, was very much a do-it-yourself (DIY) affair at this time.

In 1936, an ophthalmologist from Glendale, California, named Orrie E. Ghrist assembled a pair of 8mm cameras and projectors for 3D shooting; he subsequently wrote about them for Movie Makers Magazine. Ghrist interlocked the cameras on a custom twin-bar of his design and created a link between two projectors to make them run in sync. By the 1940s, Ghrist had interlocked a pair of 16mm movie cameras for 3D shooting.