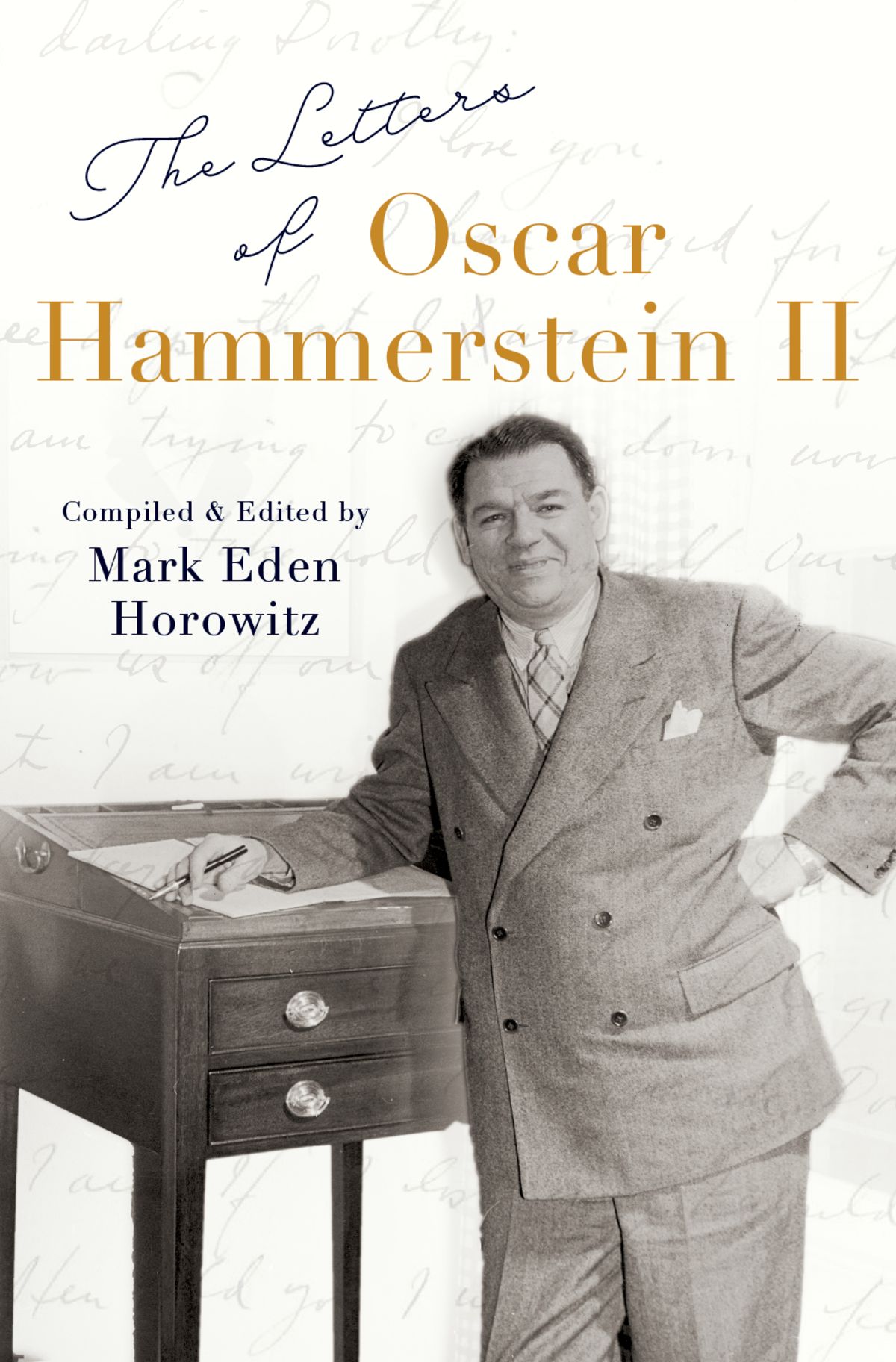

The Letters of Oscar Hammerstein II

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Mark Eden Horowitz 2022

Correspondence by Oscar Hammerstein II used by

permission 2021 by Hammerstein Properties LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780197538180

eISBN 9780197538203

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197538180.001.0001

Table of Contents

Oscar Hammerstein II is, I believe, the most consequential figure in the history of the American musical. His career spanned from 1920 to 1960, and in those forty years he so transformed our understanding of what musicals could be that any post-Hammerstein musical owes him a direct debt. Having spent the last two-and-a-half years working with his correspondence, I am convinced that Hammerstein was not only a great man of the theatera richly talented writer and an astute businessmanbut also a profoundly good human being.

Because it is his songs that are ubiquitous, Hammerstein is primarily categorized as a lyricist. He is usually placed among his contemporaries Irving Berlin, Lorenz Hart, Ira Gershwin, and Cole Porterheady company, but one in which he is sometimes dismissed as the sentimentalist. Of course he could be as clever and witty as any of them, but he was less interested in showing off than in being true to his characters. He was more concerned with his songs integration within the context of their shows than he was with their potential for being performed, recorded, or broadcast outside the theater. Thats not to suggest he was uninterested in these opportunitiesof all of his contemporaries, he was probably the canniest and most successful businessman. But as he wrote in one letter, The songs are there only to serve the play, and not vice versa.

As a lyricist, Hammerstein is credited with having written (and in a few instances co-written) the lyrics for approximately 850 songs. The majority of them were written for about forty-five musicals. Most of these songs were for Broadway, though some were for films, a few were for London, oneCinderellawas for television. There were also a couple of odd stragglersa revue at the Worlds Fair and a show that never made it to Broadway or London. For most stage musicals he wrote between a dozen and nineteen songs that stayed in the show, and a handful that ended-up being cut, if they were ever performed at all. And he wrote a modest number of non-show songs, The Last Time I Saw Paris being the most notable. But Oscar was far more than a lyricist.

Oscar wrote (or co-wrote) the scripts to at least fifty dramatic works. Most of these were librettos for stage musicals, but nine are screenplays, three are straight plays, and one is a teleplay. Oscar is credited with directing, staging, or supervising approximately a dozen shows (again, sometimes in collaboration), beginning with the original productions of Show Boat (1927), Music in the Air (1932), and Very Warm for May (1939). And it is widely believed that he ended up directing several shows for which he was uncredited.

In the theatrical world, Rodgers and Hammerstein has a long and impressive reputation (the addition of Organization came after Oscar died). But Oscar was an involved and shrewd businessman long before his collaboration with Rodgers. He completed two years at Columbia Law and for a brief time also worked for a law firm. After abandoning law school he convinced his uncle, Arthur Hammerstein (a successful producer in his own right), to hire him. Oscar worked as a production stage manager and, whether actively taught by his uncle, or learning by observing, he mastered the business.

Oscar established a professional relationship with attorney Howard Reinheimer by the mid-1920s. Reinheimer, a few years Oscars junior, also went to Columbia and graduated from Columbia Law. By 1930 he was not only Oscars close friend and attorney, but for all intents and purposes, his accountant and business advisor as well. In 1937 Reinheimer famously acquired the rights to seventy-two musical productions from the Florenz Ziegfeld estate on behalf of five clientsIrving Berlin, Jerome Kern, Sigmund Romberg, Otto Harbach, and Oscar Hammerstein.

Oscar was a producer in his own right by at least 1933, with Ball at the Savoy in London. In 1938 Oscar produced two straight plays on Broadway, although neither was a commercial success. And during his two Hollywood sojourns in the 1930s, Oscar was being courted by movie studios and seriously considered moving into the production side of filmmaking.

In 1942 when Oscar and Richard Rodgers began their collaboration and then formed their business partnership, Reinheimer was all but a third unnamed partner. By my count, Rodgers and Hammerstein produced twelve shows on Broadway. Because of obligations for their own works to the Theatre Guild, the first three were shows they didnt writethe plays I Remember Mama, and John Loves Mary, plus the Irving Berlin musical Annie Get Your Gun, a mega hit. In addition to their twelve original Broadway shows, Rodgers and Hammerstein produced two City Center revivals, one play that closed out-of-town, and the film of Oklahoma! Most of these shows were also sent on national tours. Then there was London where, under the name Williamson Music Ltd. (both Oscars and Richard Rodgers fathers were named William), they again produced their own productions plus several plays and musicals by other authors. And they managed the leasing of their shows for other productions, both nationally and internationally.

Rodgers and Hammerstein were hands-on producers, concerned with every aspect of their properties, including casting; hiring directors, designers, stage managers, and other artistic and managerial personnel; and overseeing advertising and promotion. Their shows were products they oversaw, regularly visiting productions to make sure standards were maintained. Over time multiple corporations were formed, including a music publishing company, an entity for the leasing of shows, and another for renting theater equipment. In collaboration and with guidance from Reinheimer they were not only major players, but innovators in the business of show business.

With his slow and thoughtful baritone, Oscar embodied gravitas. His opinion and counsel were highly valued. While not officially a play doctor, he read innumerable scripts, and visited rehearsals, out-of-town tryouts, previews, and productions (sometimes as a potential producer, but often just as a friend or colleague). He gave the best, most helpful advice he could. He also received unsolicited lyrics and songs, but (on legal advice), he usually and regretfully declined to look at the songs lest he later be accused of plagiarism.