Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

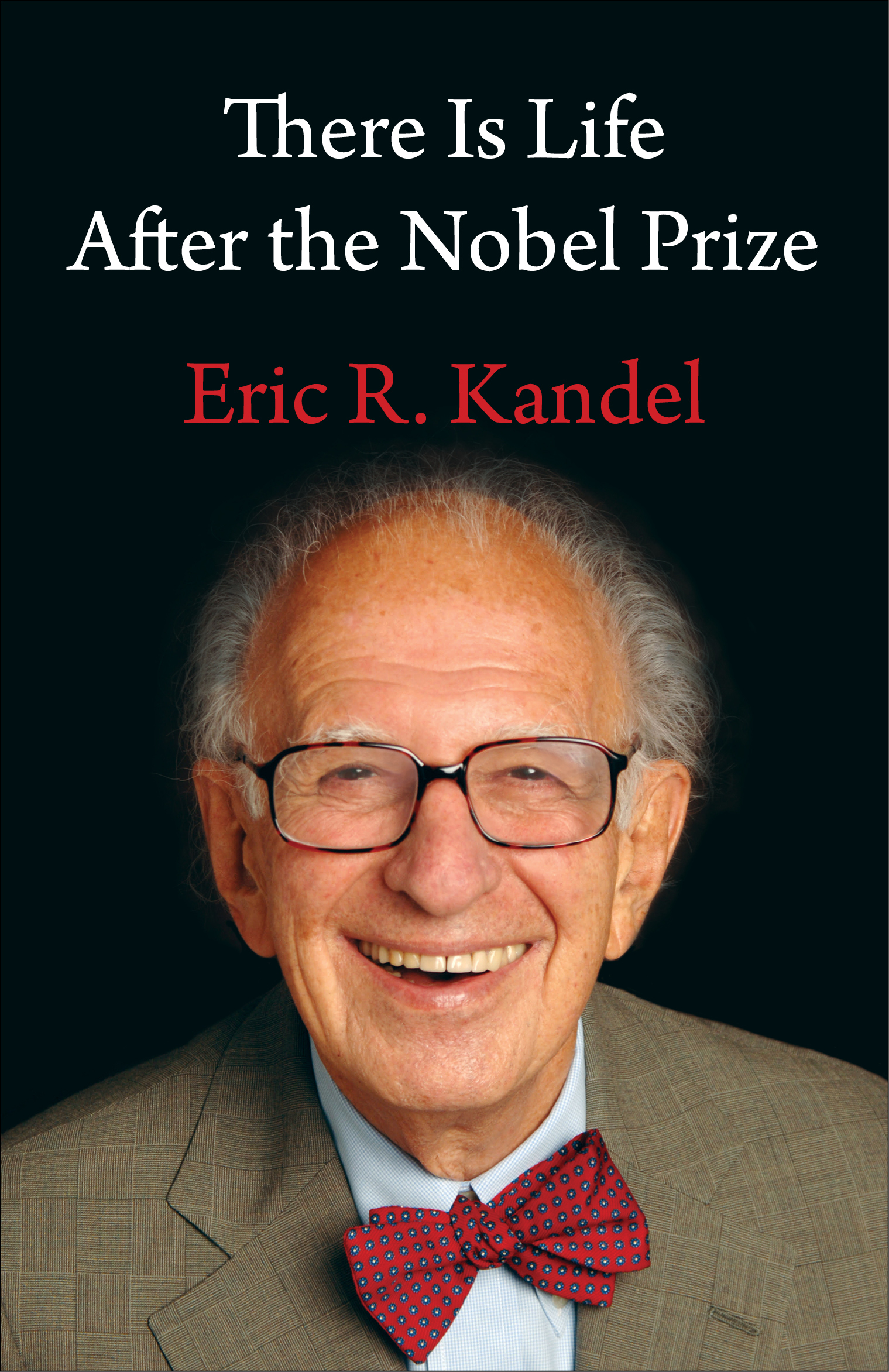

THERE IS LIFE AFTER THE NOBEL PRIZE

Eric Kandel receiving the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, Stockholm, Sweden, December 10, 2000

The Nobel Foundation, photo: Hans Mehlin

ERIC R. KANDEL

THERE IS LIFE AFTER THE NOBEL PRIZE

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New YorkChichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2022 Eric R. Kandel

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-55346-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kandel, Eric R., author.

Title: There is life after the Nobel Prize / Eric R. Kandel.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021021959 (print) | LCCN 2021021960 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231200141 (hardback)

Subjects: LCSH: Kandel, Eric R. | Columbia UniversityFacultyBiography. | Howard Hughes Medical Institute. | NeuroscientistsUnited StatesBiography. | Medical scientistsUnited StatesBiography. | Nobel Prize winnersUnited StatesBiography. | NeurosciencesResearch. | Molecular neurobiologyResearch. | MemoryPhysiological aspectsResearch.

Classification: LCC RC339.52.K362 A33 2022 (print) | LCC RC339.52.K362 (ebook) | DDC 616.80092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021021959

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021021960

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

Cover image: Eve Vagg

To Denise,

my wonderful wife and my constant source of inspiration

CONTENTS

S ince the early 1960s my wife, Denise, and I have spent much of each August in the town of Wellfleet on Cape Cod. In 1976 we bought a summer home in the area; the house has a beautiful view of, and direct access to, Wellfleet Bay and is a lovely place for boating and swimming. I also enjoy playing tennis on the superb clay courts at Olivers Tennis Club, a ten-minute drive from our house. Most important, August is an opportunity for Denise and me to have a peaceful vacation and to get together with our two children, Paul and Minouche, and their families, who come for at least part of the month.

One day in August 1996, as Denise and I were outside hanging the laundry up to dry, the phone rang inside the house. I went to answer it and found Stephen Koslow, my program officer from the National Institute of Mental Health, on the line. He told me that the grant Id applied for had been awarded and should be funded within a reasonable period of time. He then added that he and a number of people at NIMH thought I would get the Nobel Prize.

FIGURE INT.1 Denise and me on our wedding day, June 10, 1956.

After I hung up the phone, I went back outside and continued to hang the laundry. I told Denise that Koslow thought I was going to get the Nobel Prize. To my astonishment she responded, I hope not soon.

I turned to her and said, What do you mean not soon? How could you, my wife, say that?

Denise reminded me that when she was a graduate student in sociology at Columbia, she worked with Robert Merton and Harriet Zuckerman, who studied people who had won various prizes, including the Nobel Prize. They found that, by and large, after someone has won the Nobel Prize, he or she does not contribute much more to science. They become too occupied with ceremonial and social activities. You still have a few ideas, she said. Play them out. There is lots of time for the Nobel Prize later on.

So four years later, on October 9, 2000, when I received a telephone call from the Nobel committee telling me that I had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for my work on the biological basis of learning and memory, I realized that in addition to the pleasures and gratification of this remarkable award, I now had a challenge on my hands: I had to prove to Denise that I was not yet completely dead intellectually.

My aim in writing this book is to affirm that winning the Nobel Prize does not presage ones intellectual demise. Quite the contrary! It can spark new and unexpected creative endeavors and experiences that coexist in harmony with continued progress in ones scientific work. In the following pages I describe the post-Nobel years of my lifemy very enjoyable and, I like to think, productive research years in neuroscience at Columbia University, as well as the opportunity I had to help shape the future of interdisciplinary research at Columbias Mind Brain Behavior Institute. I also describe the wonderful new experience of imparting knowledge about mind, brain, and behavior to the general public, a public that, I now appreciate, is eager to learn and to know more about brain science and brain disorders.

I n 1974 I was invited to move from New York University, where Alden Spencer, James Schwartz, and I had formed the nucleus of the Division of Neurobiology and Behavior, to the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, where I would be founding director of the Center for Neurobiology and Behavior.

The move was attractive to me for several reasons. Historically, Columbia had a strong tradition in neurology and psychiatry, and a friend and former clinical teacher of mine, Lewis (Bud) Rowland, was about to assume the chairmanship of the Department of Neurology. In addition, my first experience in neurobiology had been at Columbia. In 1955, while finishing medical school at NYU, I decided to take an elective course in basic neuroscience at Columbia with Harry Grundfest. At that time, no one on the faculty at NYU was doing basic neural science, and Grundfest was the most intellectually interesting neurobiologist in New York. The experience of working with him altered my career and my life. Several years later, when Grundfest retired, I was recruited to replace him. Finally, Denise was on the Columbia faculty and our house in Riverdale was near the university, so a move to Columbia would greatly simplify our lives. I decided to leave NYU and was able to persuade Schwartz, Spencer, and Irving Kupfermann to join me. In 1983 I became a University Professor at Columbia.

In 1984 Donald Fredrickson, the newly appointed president of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, asked Schwartz, Richard Axel, and me to form the nucleus of a Howard Hughes Medical Institute at Columbia devoted to molecular neural science. The institute gave us the opportunity to recruit from Harvard both Thomas Jessell and Gary Struhl, as well as to keep Steven Siegelbaum at Columbia. So I resigned as director of the Center for Neurobiology and Behavior to become a Senior Investigator at the newly formed Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) at Columbia University.