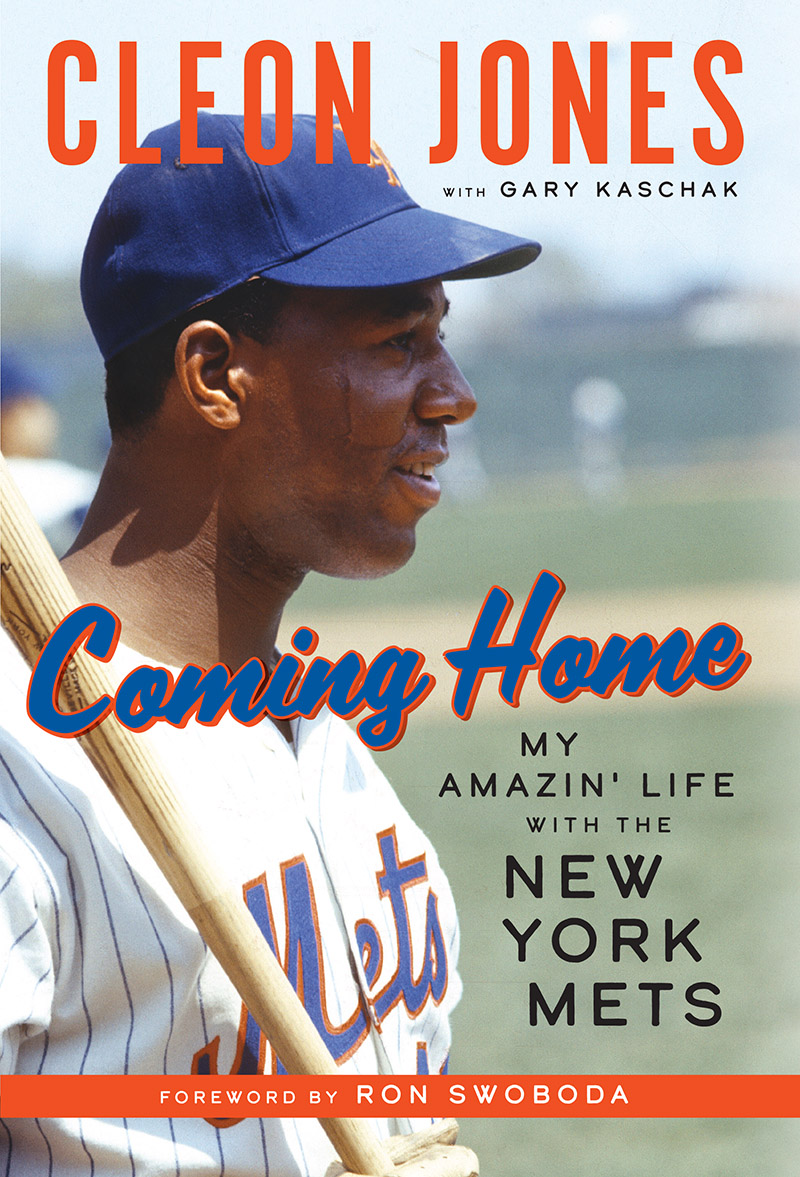

To my wife of 58 years, Angela; our children, Anja and Cleon Jr.; our grandchildren, Albert, Anjelica, Myles, Joshua, and Morgan; and our great-granddaughter, Autumn

To Valena McCants, Tom and Vivian Withers, James Fat Robertson, and Clyde and Liddie Gray

To the Plateau/Africatown Community, the Africatown Community Development Corporation (ACDC), the Africatown Business and Community Panel (ABCP), and the Cleon Jones Last Out Community Foundation

To the New York Mets Family Jill Stork and the Alabama Power Family Mr. and Mrs. Nathaniel Mosley Mr. William Bill and Hattie Clark Tom Clark and his family

To my adopted daughter, Monique Rogers, who is very instrumental in my life and dedicated to helping people in the Plateau/Africatown Community and in all of Mobile County live a better quality of life, which is our goal and the life-long mission of my wife and myself

To all of the names not mentioned that were instrumental in my life and in my baseball career, I know that there are many, and I carry them in my heartespecially to my parents, Joseph and Juanita Jones; my grandmother, Myrtle Henson; and my great-grandmother, Susie Henson, the two solid rocks of my life

To Gary Kaschak and family and Rene LeRoux and family

Cleon Joseph Jones

Contents

Foreword by Ron Swoboda

As a white kid growing up in Baltimore County, a thoroughly segregated community, circa 1960s, arriving in St. Petersburg, Florida, in 1964 for my first taste of professional baseball was a bit of a culture shock. I hadnt played with or against any Black players in my amateur career to date and didnt know a soul from the Deep South. I knew Cleon was from Mobile, Alabama, where a ton of great major leaguers were born and raised, guys like Hank Aaron, Willie McCovey, Billy Williams, and former Mets like Tommie Agee and Amos Otis. If you expand that list to the state of Alabama, the numbers will blow your mind.

What rocked me was watching Cleon at home plate. While I was hoping I had something to offer the professional game, Cleon looked like somebody who had figured it out. At the time, it never occurred to me to approach him about hitting because, honestly, coming from the eastern part of the country, with Cleons Deep South drawl, the words came fast and furious at firstI had no clue what he was talking about.

Fortunately, we got to spend a fair amount of time together off the field, and my ear eventually became tuned to Cleons patois, and I was a better person for it. It turns out we had a lot in common. Coming from Baltimore County, I was hip to the seafood economy around the Chesapeake Bay with its bounty of blue crabs, fish, and oysters. Coming from Mobile, Cleon knew all about blue crabsexcept they boiled them there in a zesty broth, and we Marylanders cooked the crabs with live steam in a pot with a heavy and hot, spicy coating. Bottom line was when my mom and dad came up to New York with a mess of Maryland steamed crabs, Cleon knew how to crack them and eat them by the dozen. Mix in a couple of cold beers, and Cleon might launch into a tale about a friend from home who would catch fish if you just turned on the faucet. And those were good times.

They got better in 1969 when the Mets matured quietly into a contender, and Cleon, with a few major league seasons under his belt, vaulted into the National League batting race with the likes of Pete Rose and Roberto Clemente. It was always interesting to me that the only hitting aid we had back then were some loops of 16mm film that you could project on the wall in this little back room off of our clubhouse. The only person I ever saw in there, feeding the loops through the projector aimed at the wall in little images that looked like 1950s television, was Cleon Jones. I couldnt spend five minutes in that constricted place. Cleon told me recently that he watched more than his own at-bats. I watched other guys when they were going good and what they were doing at the plate, and when they were going bad figuring out the things that were keeping them from hitting the ball good. The .340 average that Cleon posted put him just behind Clemente at .345 and Rose, leading the way at .348. As they might say in Alabama, that was tall cotton.

Theres no doubt in my mind that Cleon helped his Mobile homeboy Tommie Agee rebound offensively from an awful 1968. As a student of hitting, you glean things from everywhere. I credit Tommy Davis, who was a Met in 1967, with helping me to my best batting average of .280 just by being in the batting order ahead of me and getting me better pitches to hit. But Cleon was in the graduate level of hitting. Tommy Davis and I talked a lot, Cleon said. His point was that the body was just support for the hitting mechanism, the hands were the weapons. In those hands Cleon carried a large piece of wood up to home plate and what he could do with 37 or 38 ounces of northern ash spoke loudly.

I, on the other hand, floundered offensively through the first half of 1969. And with Gil Hodges, you hit or you sit. Pretty simple. Funny thing was, Cleon was having some trouble with his ankle, and we were having some trouble with the Astros. Houston beat the crap out of us in 1969. They won 10 of 12 games we played, and on Wednesday, July 3o, in Shea Stadium it only got worse. After Houston strapped a 163 bruising on us in Game 1, we were down 100 in Game 2 after Johnny Edwards doubled in Doug Rader from first base. I was on the pines, where I belonged, but that would change.

Much was written about what happened next. The writers covering the team seemed to focus on what they thought was Cleons lack of hustle after Edwards line drive down the left-field line. Gil Hodges took the slowest walk youve ever seen by a manager who had some distance to cover. Gil walked by the pitcher, Nolan Ryan, a Texan taking his turn at getting shellacked by Houston. Past our shortstop, Bud Harrelson, who breathed a big sigh of relief. And on to left field, where Gil had a prolonged discussion with Cleon and finally lifted him from the game and put me into left field. Cleon all these years later tells me the conversation was never accusatory, never berating. Cleon told me, He asked me if I was hurt, and I told him to look at the water that back then tended to collect in the outfield at Shea and how muddy it was. And when Gil suggested maybe Cleon should leave the game, Cleon agreed. Today, as he did back then, Cleon felt like he had a motive to shake the team up. Weve talked about this before, and I think Gil looked around the dugout and didnt see anybody too upset about us having our butts handed to us by the Astros and made one of the most impressive scenes of the season purely for effect. Im here to tell you, it worked.

The 1969 New York Mets went on a roll, winning close to three out of every four games, running down the Chicago Cubs, who were leading the National League East all year, and we never looked back. I went on a useful offensive run that lasted through August and September and into the World Series. Cleon was back into the lineup after his ankle calmed down, and he continued the kind of hitting that led us to a World Series win.

Weve stayed friends for more than a half-century now. And he has only grown from the man and the player that he was with the Metsback home in Africatown, Alabama, which was absorbed into Mobile, and historically is where the last cargo of Africans for delivery into slavery occurred in 1860. Cleons work with the Africatown Development Corporation, painting homes and replacing roofs for folks who would otherwise do without, only shows the heart and soul of a man who will never forget where he came from and will never quit trying to make it a better place.