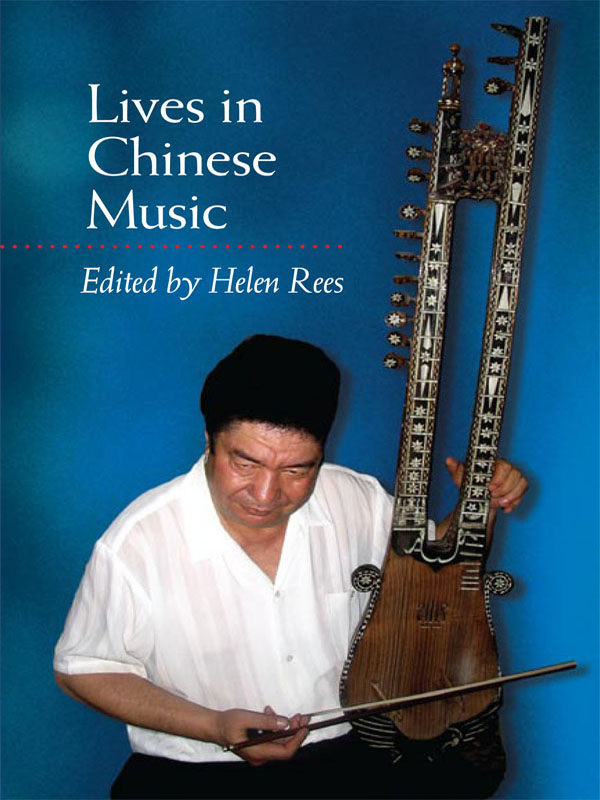

Helen Rees - Lives in Chinese Music

Here you can read online Helen Rees - Lives in Chinese Music full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, publisher: University of Illinois Press, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Lives in Chinese Music

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Illinois Press

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Lives in Chinese Music: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Lives in Chinese Music" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Using biography to deepen understanding of Chinese music, contributors present richly contextualized portraits of rural folk singers, urban opera singers, literati, and musicians on both geographic and cultural frontiers. The topics investigated by these authors provide fresh insights into issues such as the urban-rural divide, the position of ethnic minorities within the Peoples Republic of China, the adaptation of performing arts to modernizing trends of the twentieth century, and the use of the arts for propaganda and commercial purposes.

The social and political history of China serves as a backdrop to these discussions of music and culture, as the lives chronicled here illuminate experiences from the pre-Communist period through the Cultural Revolution to the present. Showcasing multiple facets of Chinese musical life, this collection is especially effective in taking advantage of the liberalization of mainland China that has permitted researchers to work closely with artists and to discuss the interactions of life and local and national histories in musicians experiences.

Contributors are Nimrod Baranovitch, Rachel Harris, Frank Kouwenhoven, Tong Soon Lee, Peter Micic, Helen Rees, Antoinet Schimmelpenninck, Shao Binsun, Jonathan P. J. Stock, and Bell Yung.

|Contents Acknowledgements Introduction: Writing Lives in Chinese Music Helen Rees Part I. Regional Focus: The Yangtze River Delta 1. Zhao Yongming: Portrait of a Mountain Song Cicada Frank Kouwenhoven and Antoinet Schimmelpenninck 2. Shao Binsun and Huju Traditional Opera in Shanghai Jonathan P. J. Stock with Shao Binsun Part II. The Literati 3. Tsar Teh-Yun at Age 100: A Life of Qin Music, Poetry and Calligraphy Bell Yung 4. Gathering a Nations Music: A Life of Yang Yinliu Peter Micic Part III. Music on the Cultural Frontiers 5. Grace Liu and Cantonese Opera in England: Becoming Chinese Overseas Tong Soon Lee 6. Abdulla Mjnun: Muqam Expert Rachel Harris 7. Compliance, Autonomy, and Resistance of a Chinese State Artist: The Case of Mongolian Musician Teng Geer Nimrod Baranovitch Contributors Index|In a difficult field...[this] book breaks new ground by bringing us the real lives of real musicians.Songlines

A magnificent contribution to English-language scholarship on the music of China. . . . The exceptional writing throughout the volume results in a collection that displays ethnographic research and writing at its best. The World of Music

The essays integrate the life stories of each musician into political, social, and economic developments in China. . . . Recommended.Choice

|

Helen Rees is a professor of ethnomusicology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the author of Echoes of History: Naxi Music in Modern China.

Helen Rees: author's other books

Who wrote Lives in Chinese Music? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper. m (Danielson 1997) and Latin great Tito Puente (Loza 1999). However, numerous other more generically titled monographs also highlight individual agency, interpretations, and experience. Deborah Wong neatly encapsulates her incorporation of all these elements in her recent book on Asian American musicians: I argue that music is performative and that it speaks with considerable power and subtlety as a discourse of difference. Indeed, the sounds I address are many thingsloud, angry, anguished, joyful, defiant, nostalgicand the Asian American musicians who make this noise have a lot to say about what they are doing. I trace their words, their music and how they are heard (2004:3).

m (Danielson 1997) and Latin great Tito Puente (Loza 1999). However, numerous other more generically titled monographs also highlight individual agency, interpretations, and experience. Deborah Wong neatly encapsulates her incorporation of all these elements in her recent book on Asian American musicians: I argue that music is performative and that it speaks with considerable power and subtlety as a discourse of difference. Indeed, the sounds I address are many thingsloud, angry, anguished, joyful, defiant, nostalgicand the Asian American musicians who make this noise have a lot to say about what they are doing. I trace their words, their music and how they are heard (2004:3).