I would like to thank all the people who have contributed to the completion and production of this encyclopedia on traditional Chinese culture. First and foremost, my sincere and profound gratitude goes to Andrea Hartill, Senior Publisher of Routledge, for her support and encouragement to this encyclopedia project. My thanks also go to Claire Margerison, Senior Editorial Assistant of Routledge, and Holly Smithson for their professionalism in producing this encyclopedia. Each and every contributor to this volume deserves my highest admiration and respect. It is through their writings that the English-reading world could have a good understanding of the various aspects of Chinese culture.

Special thanks are due to colleagues who helped to introduce experts to me to write on some topics in this encyclopedia. In this regard, I thank Professor Hua Wei of The Chinese University of Hong Kong and Professor Li Ruru of the University of Leeds for introducing prominent scholars to engage in this project.

The author and publishers would like to thank the following copyright holders for permission to reproduce the following material:

- , courtesy of Li Yurus family.

- , courtesy of the National Peking Opera Company.

- , courtesy of Shanghai Jingju Theatre.

All works of calligraphy by Professor Xu Yangsheng in , courtesy of Professor Xu.

, reproduced partially with kind permission of The Commercial Press (H.K.).

on behalf of The Permanent Conference on Chinese Oral and Performing Literature, Inc.

1

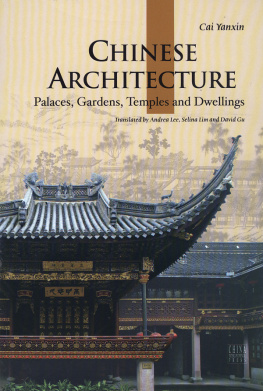

ARCHITECTURE IN TRADITIONAL CHINA

Nancy S. Steinhardt

Introduction

Architecture stands across the nearly ten million square kilometres of land on the eastern side of the Asian continent that today comprises China. Above ground, buildings remain from the earliest centuries CE ; the archaeological record of Chinese architecture is more than five millennia older. Chinas major building materials through the entire period have been wood, brick, and stone. From group settlements to multiple-walled urban centres, whether royal or vernacular, religious or secular, public or private, Chinas built environment has been erected almost exclusively by craftsmen and artisans. Chinese architecture is distinguished from buildings worldwide by the length and consistency of its building tradition and so few architects whose names are associated with it.

Wood joinery and the timber frame that is achieved are defining features of Chinese architecture. The interlocking network of vertical, horizontal, and sometimes diagonal or curved wooden members is the result of a modular system whereby the measurement of almost any piece can be calculated from the dimensions of another piece. Modular construction means that from individual components such as pillars to entire planar sections of a building, all can be replicated, increased, decreased, repositioned, or eliminated to change a temple into a palace, a shrine into a house, or a humble dwelling into a lavish family compound. The proportional relationships make it possible to repair or replace damaged parts and to assemble a building in the style of the distant past.

The wooden pieces of a standard Chinese building divide into three layers: the column network, the bracket set layer, and the roof frame. Below and above these three wooden networks, buildings are made of other materials. The base of a Chinese building, the part that interfaces wood above it and earth below, is made of non-rotting material; expensive stone such as marble for an eminent structure, brick for a more humble one, and rammed earth when funds are limited. Only rarely are columns implanted directly into the ground. In more expensive buildings, columns are placed in pilasters rather than directly into a podium. Outside, the building presents as base, structure, and roof. The roof is a defining feature of Chinese architecture. Usually made of ceramic tile, glazed for more important buildings, it is one of the silent symbols that identify the status of the building. The simple, hipped roof covers Chinas most eminent buildings, followed in status by the hip-gable roof, with overhanging eaves of yet lower status. The main ridge of any of them may be decorated, adding to its status.

The arrangement of Chinese buildings in space similarly exhibits continuity over millennia. The horizontal axis is primary. It is usually northsouth and the most important buildings are positioned on it. Spatial magnitude is expressed by longer and longer lines of buildings along horizontal planes, not vertically, for space requires ownership of land; someone with wealth expands one-storey buildings across more and more space. Even Chinas most important buildings, including the Hall of Supreme Harmony in the Forbidden City, are only one storey. The height of columns across the front faade of the Hall of Supreme Harmony is about 8.43 metres, a mere five times the height of a man.

Chinese buildings are positioned around courtyards according to a principle known as four-sided enclosure. When only three sides of a courtyard have buildings, the principle is called three-sided enclosure, for the fourth side is implied. South, the orientation of the Forbidden City, is the cardinal direction. Every courtyard has one most important structure. Almost every courtyard and building complex is entered through a gate. Gates are so important that in rare cases of a single building, it is never in total isolation because a gate is in front of it. The gate is psychological as much as physical. Like the enclosing space to which a gate may join, it marks the boundary between more sanctified or imperial space behind and the profane world outside it.

A final feature distinguishes the Chinese building tradition from all others. Upon the establishment of the Peoples Republic on 1 October 1949, archaeology became a state-sponsored enterprise. Since then, the history of Chinese architecture has been written through physical evidence above and below ground.

Chinas earliest architecture

The physical evidence of cities in China is earlier than evidence of individual buildings, probably because buildings were made of perishable materials whereas city walls were constructed of rammed earth. Urbanism in China began by the sixth millennium BCE . For the next four millennia, the evidence is primarily archaeological, with a wall defining a city. This physical definition is reflected in the translation of the Chinese character cheng as both wall and city. When a wall is found, Chinese archaeologists assume it signifies a group settlement. At least one wall, at Pingliangtai in Henan, was squarish, about 185 metres on each side. The square is an ideal shape that would be associated with Chinese cities through history.

Much of Chinas earliest architecture developed along major rivers. If we believe texts, the earliest Chinese residences were below ground in the form of cave dwellings and elevated aboveground on wooden stilts. Evidence for both types has been found from the Neolithic period (ca. 60002000 BCE ) along Chinas two major rivers: semi-subterranean dwellings along the Yellow River in the North and stilted houses near the Yangzi River (Changjiang) in the south. The southern site Hemudu in Yuyao county, Zhejiang, preserves evidence of timber-framing, including both straight posts for raising a structure above swampland and interlocking wooden pieces. Dadiwan in Gansu province of western China had two structures joined by an arcade. One of the largest Neolithic sites is at Banpo, due east of the modern city Xian, where it is expected that size of ruins will be sixty square kilometres. Banpo had circular and four-sided dwellings, drainage ditches, and a large structure known as the Great House that may have been used for ceremonies.