First published 2016

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2016 selection and editorial matter, Chan Sin-wai; individual chapters, the contributors

The right of Chan Sin-wai to be identified as author of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

The Routledge encyclopedia of the Chinese language / edited by Chan Sin-wai; assisted by

Florence Li Wing Yee and James Minett.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Chinese languageEncyclopedias. 2. Chinese philologyEncyclopedias. 3. Chinese characters

Encyclopedias. 4. Chinese languageAcquisition. I. Chan, Sin-wai, editor. II. Li Wing Yee, Florence,

editor. III. Minett, James W., editor.

PL1031.R68 2015

495.13dc23

2015017474

ISBN: 978-0-415-53970-8 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-67554-1 (ebk)

Typeset in Times New Roman

by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong

William S.-Y. Wang

Department of Chinese and Bilingual Studies

Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China

Huang Chu-Ren

Department of Chinese and Bilingual Studies

Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China

Feng Shengli

Department of Chinese

The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Cao Guangshun

Institute of Linguistics

Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China

36

Modern Chinese: Written Chinese

Feng Shengli

THE CHINESE UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG, HONG KONG, CHINA

This chapter, based on Feng (2009) and Sun (2012), shows how written Chinese is different from spoken Chinese in modern times, how the formal register system of written Chinese has developed since the May Fourth Movement, and, finally, what principles the formal register grammar must observe.

1. Spoken and written Chinese

Modern written Chinese () is a result of the May Fourth Movement (1919). Before then, Chinese intellectuals (which included virtually everyone who was literate) wrote in classical (literary) Chinese. Although there were proposals for writing in the vernacular before the May Fourth Movement, with people like Huang Zunxian promoting My hand writes [what] my mouth [says] () in the late Qing dynasty (1644 1911), the shift from writing in literary Chinese to writing in the vernacular did not actually occur until the Literary Revolution (), launched by Hu Shi and Chen Duxiu in 1919.

One important argument for replacing literary Chinese with the vernacular in writing was, according to Hu Shi, that literary Chinese became a dead language thousands of years ago. However, what is striking is the fact that there are still remnants of literary Chinese within Modern Chinese vernacular writing. For example:

- (1) ,,,,,

Of course, this does not mean that local people have been entirely integrated into the Han nationality in all of the areas where the Han have penetrated. In fact, this is not so because even now there are many minorities which have mixed with the Han race within Han regions.

Fei Xiaotong , Minority Development in China

In (1) there are about 44 morphemes (free, as well as bound) and 11 of them are taken from Classical Chinese, e.g. extend to, take as, is certainly not like this, even now, live together and within. Actually, classical expressions like these are not merely remnants, they are actually required to make the written text sound natural. Zhang (2002) promoted that people should incorporate some literary expressions into their own writing() (Zhang 2002: 134).

Why is this syncretization of literary forms into the vernacular necessary? Feng (2005) argued that it is essentially a result of register requirements, and Sun (2012) also argued that literary Chinese serves a distinctive linguistic function in modern times which has ensured its survival. In other words, modern formal Chinese would have been difficult to develop without utilizing some literary Chinese. Thus, literary and colloquial Chinese cannot truly be divorced in the modern context of language communication as will be explained below.

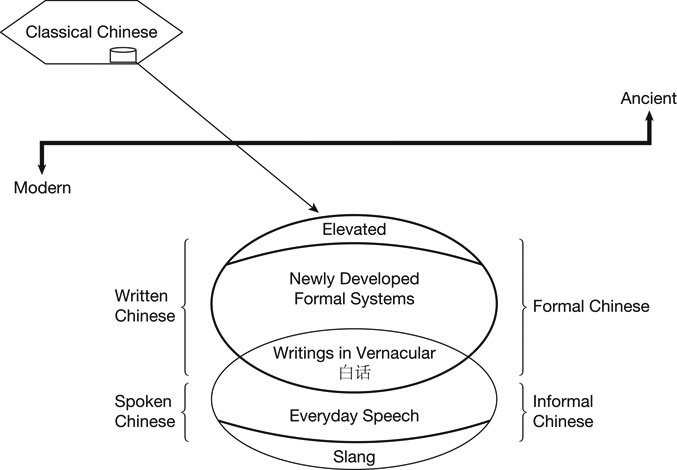

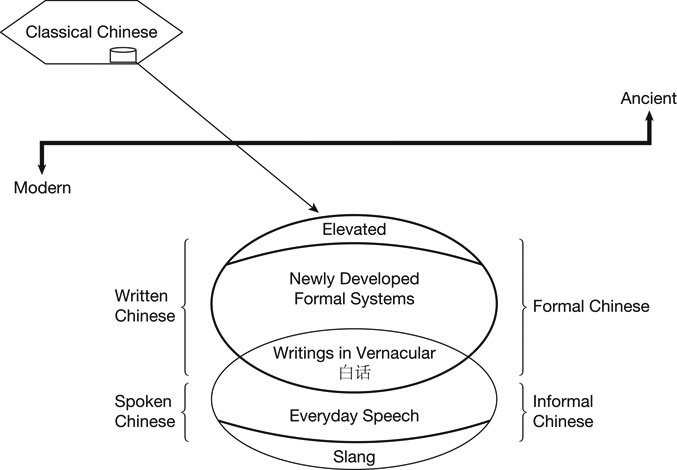

It is well known that if a writing style is too literary it may not easily be understood by ordinary or sometimes even educated people; while if it is too colloquial (informal) it will not be acceptable in formal situations because of its lack of formality. The traditional dilemma of separating colloquial expressions from literary diction in modern written Chinese has arisen from the inseparability of vernacular grammar with literary expressions which makes it possible to create a formal register of writing. Thus, the formal and informal styles of Chinese can be analyzed as in .

illustrates several important points which are elaborated on below. First, what is called written Chinese should be defined in terms of the formal style of writing in Modern Chinese.

Second, the notions of informal/formal and spoken/written are not isomorphic, i.e. formal does not only imply written, nor does spoken always refer to informal, and vice versa. Formal Chinese is also an utterable language and is not reserved only for writing, even if written language usually refers to formal or elevated registers. The definition given in example (2a) implies that formal Chinese can be both spoken and written.

Diagram of formal and informal Chinese (Feng 2006)

Third, Classical Chinese and Modern Chinese should be clearly distinguished here: Classical Chinese refers to the language with many linguistic features of the Han and pre-Han periods (i.e. up to the third century) which remained prevalent up until the May Fourth Movement, while Modern Chinese is defined in terms of its auditory comprehensibility to the ordinary people of today. Thus, according to Feng (2009), speech that cannot be understood by means of its sound alone by an ordinary high school graduate will not be considered modern (for a more detailed discussion of this criterion, see Feng 2003a, 2003b; Sun 2012).

Fourth, formal expressions in Modern Chinese come from two major sources: Classical Chinese and completely new expressions that developed within the formal system itself after 1911. For example, there are systematically developed formal expressions like jinxing carry out:

| (2) | (a) |

| Women | yiding | yao | dui | zhege | wenti | jinxing | yanjiu. |

| we | definitely | need | towards | this | issue | carry-out |