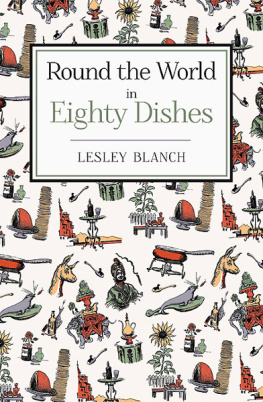

The author wishes to acknowledge the immortal memory of Jules Vernes Round

the World in Eighty Days

Published in 2012 by

Grub Street

4 Rainham Close

London SW11 6SS

www.grubstreet.co.uk

Twitter @grub_street

Text and illustration copyright Lesley Blanch 1956, 1992, 2012

Copyright this edition Grub Street 2012

Design: Sarah Driver

First published in 1956 by John Murray Limited, London

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in

a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission

of the publisher.

A CIP catalogue for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-908117-18-2

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-909808-71-3

Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG, Bodmin, Cornwall

on FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) paper

Note from the Publisher

The only change that has been made to this classic work published in 1956 has

been the addition of metric measures, where appropriate, to assist the modern

day cook.

Authors Note to 1992 Edition

When I wrote this book nearly forty years ago, people in England were still enduring many post-war restrictions on both travelling and eating. But a benign fate whisked me elsewhere to follow less restricted ways, travelling widely and eating wildly. Thus, to my friends, I became an object of envy or exasperation with every postcard I sent home. (Muscat. Supper with pearl divers on their boat. Dashing lot. Shark stew and prickly fig jam for pud. Wish you were here.)

Today, everyone jets everywhere, a lemming rush to eat everything imaginable and unimaginable, while at home they can obtain dazzling ranges of frozen dishes, so there is little I can add. Nevertheless, I continue to get many requests for this early book, while faithful readers tell me they are still cooking my typical or simplified recipes with gusto.

But before any new readers start flicking over the pages, toying with the idea of making Congo Chicken or Gogel-Mogel, may I remind them when those recipes were collected, when those sketches, sketched? Since then, all over the world, political strife, terrorism, famine, television and what is described as progress, have swept away tradition and local colour, replacing them with a remorseless unification or desolation. Were I back in Roumania today I doubt any of the smiling scenes I recalled could still be found. What I wrote of it then is cruelly inapplicable now. As elsewhere flora and fauna, open spaces, free seas, are all going, going. Gone.

However, a few traces of traditional ways mostly by way of the family table do linger in some places and are cherished, almost defiantly. I hope my readers may still catch glimpses of such colours and flavours through this old book, my kitchen-window peepshow.

Lesley Blanch, 1992

To my mother Martha Blanch

Whose fireside meals I enjoyed more than other peoples banquets

FOREWORD

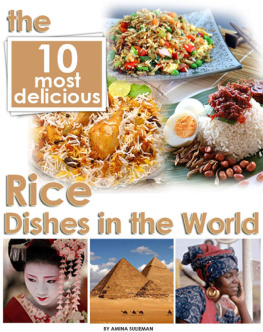

It is said that a nation is made by what it eats: undoubtedly diet affects character. Lions reared on milky mush cherish lambs. Battles have been determined by indigestion, for we all known that an army marches on its stomach. Walt Whitman, writing of Carlyle, said: Dyspepsia is to be traced in every page, and now and then fills the page . Behind the tally of genius and morals stands the stomach and gives a sort of casting vote.

Certain climates produce racial types and characteristics which are expressed individually, by different ways of eating. For example, there is a popular conception that southern food is rich and that southern passions run high. Nothing could be further from the truth. You must go to the norththe dark, ingrown, seething north of Ibsen householdsif you want to find overwhelming passions and those rich, nightmare-producing meals which, I feel, may have been responsible for some of Dostoevskys greatest flights. This north of the Karamazov brothers, of Anna Kareninas ill-fated love, of Gosta Berlings Atonement, is the land of bliini and bigos, koulobiak, and pickled herrings, sour cream, indigestion and introspection. The Mediterranean, on the contrary, is all lightnesslight food, light loves, air, sea, blueness, and dalliance. Everywhere the people are still actuated by a legacy of Greek or Roman classicisma sense of balance and logic, reflected in many aspects of their daily life, among them their eating habits, which are simple.

Lucullus, whom frugality could charm,

Ate roasted turnips at the Sabine farm.

In this part of the world it is so easy to live well, simply; so easy to love, hate, and love again . Emotions do not smoulder long here. They overboil and are renewed, easily. The sun is a powerful, life-giving force, and a drug, too, seeping that will to suffer which is so obstinately rooted in the north. Passions are soon kindled, soon extinguished in the south. No one broods, and few have indigestion.

If you travel widely, as I have had occasion to do, and look around you at what the various nations eat, and why, and how, you will see that in spite of the apparently injudicious mixtures enjoyed by many other nations few appear ( judging by statistics and the prevalence of patent medicines for indigestion) to suffer so much from stomach upsets as the tin-fed Americans and the rather plain-living British, today.

At its best, English food is wonderful: it is more often the cooking which is at fault. My book does not aim to turn you from good English food, but rather to offer you a cooks tour of supplementary dishesa look at the rest of the world by way of the kitchen table, in the hope that other peoples food will spur you to taking even more interest in your ownand, above all, in standards of good cooking. But before I plunge into the international recipes I have collected on my travels, I want to make a few remarks about the place the Ogre Calory has come to occupy in daily life, causing people to fuss over calories before they have learned to cook. He seems to have become an omnipresent shade, a far-reaching, globe-trotting kill-joy. Today, in Near Eastern countries, where famine is not unknown, and where ampler curves were once appreciated, dieticians now rear their ugly heads and there are weighing machines peppered about the streets with anxious looking, spellbound peasants climbing on to them over and over again, in the manner of fairground visitors sampling sideshows.

Once, good eating was an end in itself. People ate well, or badly: the rich ate too much and the poor did not have enough: though Dickens speaks of oysters as the poor mans food, so it seems there was compensation. Many people exceeded at table, and waistlines were lost almost as soon as first illusions. But now a shadow falls across the kitchen. A sort of collective dietetic conscience is the spectre at every feast, crying: Saccharine! Les crudits! No bread! Only one potato!

Once, British and American travellers had only to set foot abroad, on the Continent, that is, to make a series of devout gastronomic pilgrimages, moving from restaurant to centre gastronomique with that sleek, glazed-eyed look peculiar to the well-fed. But now, both at home and abroad, they sit calculating their calories (particularly the more figure-conscious Americans) as they consult the menu, juggling their personal weights and measures with that concentration ever associated with the restricted travellers financial adjustments (Not soup

Next page