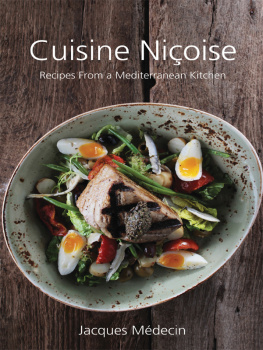

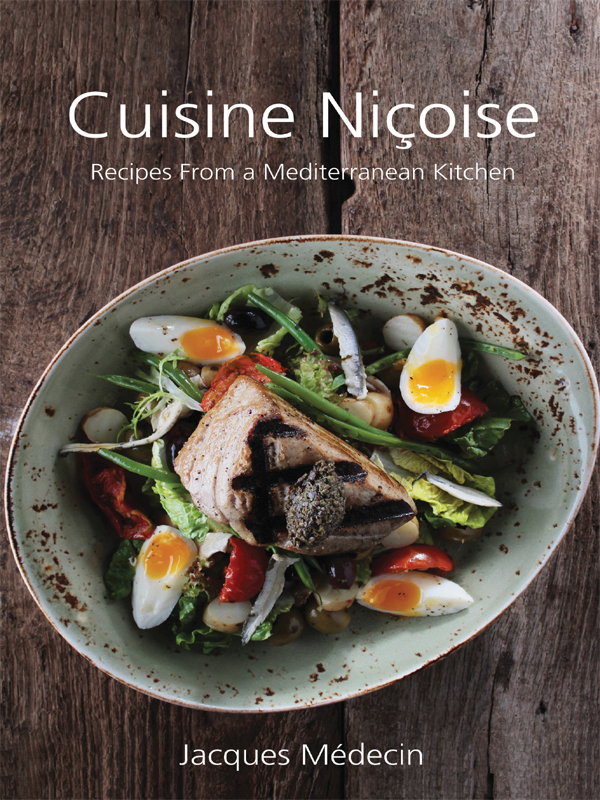

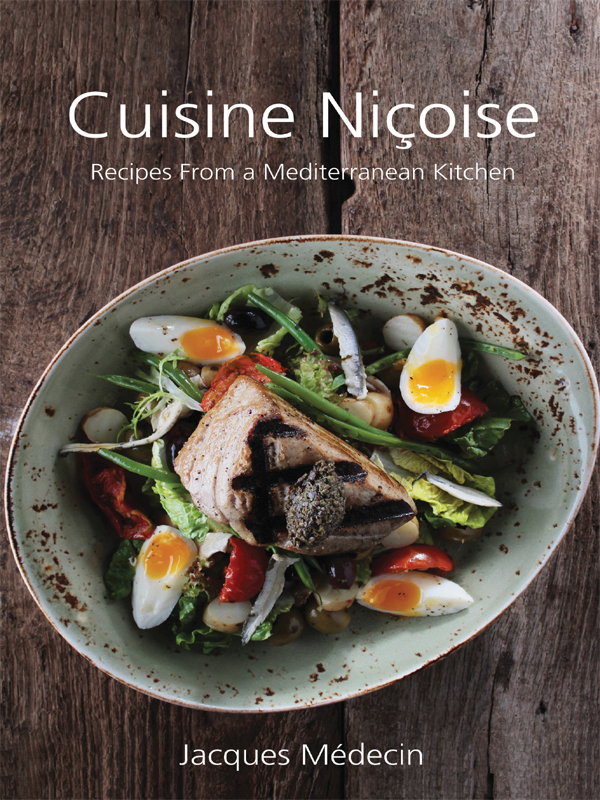

Cuisine Nioise

Cuisine Nioise

Recipes from a Mediterranean Kitchen

Jacques Mdecin

Translated and edited by Peter Graham

GRUB STREET LONDON

This edition published in 2016 by Grub Street,

4 Rainham Close, London SW11 6SS

Email:

www.grubstreet.co.uk

Copyright this edition 2016 Grub Street, London

First published as La Cuisine du Comt de Nice by Julliard 1972

Introduction and translation copyright Peter Graham, 1983, 2016

First published in Great Britain by Penguin Books Ltd, 1983

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-910690-16-1

eISBN 978-1-910690-58-1

Mobi ISBN 978-1-910690-58-1

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Publisher.

First, an explanation of this books subtitle, Recipes from a Mediterranean Kitchen. Why Mediterranean? you may be wondering. Why not French? The answer is simply that Nice has been part of France only since 1860. For almost 500 years before that (apart from a brief interlude under French rule from 1792 to 1814), Nice belonged to the House of Savoy, whose kingdom, known as the Kingdom of Sardinia, also included Savoy, Sardinia, and Piedmont (and, for part of the mid nineteenth century, almost the whole of Italy). Until 1860, there was little or nothing French about Nices culture. And its culinary traditions, although showing some Provenal and Italian influences, have always been quite individual.

To the modern mind, Nice may conjure up an image of pleasure-seeking Edwardianism. As far as its cookery is concerned, any such image is quite irrelevant. The Promenade des Anglais, the gingerbread Htel Negresco, the casinos, and the swish suburbs of Cimiez are mere accretions that have made their appearance over the last 100 years or so, thanks to the attractions of sun and an average annual temperature of 18C. They have little to do with the forces that made traditional Niois cookery what it is.

Nice and its tiny province, the Comt de Nice (which extends along the Mediterranean coast from Antibes to Monaco, and northwards up into the Alps as far as Piedmont), have always been a backwater, an enclave hemmed in by mountain and sea. As there is little arable land, Nice has never been self-sufficient, and throughout its history has suffered from a chronic shortage of wheat. In the Middle Ages, its political alliances were governed by the need to ensure regular food supplies for its inhabitants.

This historical background goes a long way towards explaining the simplicity frugality almost of Niois food. It is a far cry from the sumptuous cuisine of such rich farming provinces as Normandy or Burgundy. Herbs and other flavourings (particularly anchovy) are expertly used to enhance everyday products. Fish (readily available) and vegetables (easily grown in an ideal climate and needing little space) predominate over meat, and account for the two longest chapters in this book. And preserves of various kinds salted and dried fish, salt pork, pickled and dried vegetables, bottled fruit, raisins, nuts and so on still play the important role they did in the past, even though the eventuality of a serious food shortage has long since vanished.

The other great influence over Niois cookery has been Italian (see ), and more especially Genoese and Neapolitan. Historically, Genoa has always had strong ties with Nice, and this shows in several recipes such as pistou , a sauce derived from the Genoese pesto , and made of basil, garlic, olive oil, and Parmesan (some Niois claim that pistou travelled the other way from Nice to Genoa).

Nice was always, until recently, an important centre of trade, both by sea and by land. It exchanged its fresh fruit, vegetables, and above all olive oil for preserves brought in by foreign boats. Prominent among such preserves were salt cod ( morue) and wind-dried cod (stockfish) from Scandinavia (cod is not found in the Mediterranean). Indeed, stockfish was so enthusiastically adopted by the Niois that it has become the symbol of traditional local gastronomy.

Such openness to outside influences also explains, no doubt, why the Niois adopted such an outlandish dish as English Christmas pudding. It was probably first introduced not by English traders, who had been doing business with Nice since the sixteenth century, but by the leisured classes who began wintering there in the mid eighteenth century. Jacques Mdecin remembers his grandmother, when he was still a small boy, making what she called 'ploum-pudding for Christmas and the New Year. Set alight with lashings of rum, it was a long-anticipated treat that gave the younger members of the family a chance to taste a sweet with alcohol in it. Mdecin long assumed the pudding to be a home-grown speciality, and it was only much later that he learned of its English origins. Similarly, cheesecake can be found in Niois ptisseries : it was originally made at the request of Russian princes.

The best way to get an idea of what Niois food is all about is to stroll into the old quarter of Nice. The narrow Rue du March and the streets that form its continuation are mainly lined with tiny food shops of every description. There you will see a fairly comprehensive range of local food (and choosy local shoppers): aged Parmesans, mature Goudas, and various Niois cheeses piled teeteringly on top of each other; serried ranks of brilliant fresh fish; salted anchovies in tubs, slabs of morue , long, emaciated stockfish, barrels of olives and pickled red peppers; row upon row of green and white fresh pasta and gnocchi; strange cuttleboneshaped panisses , made of chickpea flour; socca , a very thick pancake made of the same flour, sold in chunks by street vendors; uncooked tripe hanging from hooks like thick woolly rugs; colourful displays of fruit and vegetables; and a range of charcuterie that can only excite admiration your gaze may even be returned by the spectacular porchetta , a boned, stuffed, reconstituted, and roasted piglet whose back end is cut up into huge slices (like the pig in Savignacs celebrated poster for ham).

If, on the other hand, you cannot get to Nice, Jacques Mdecins book is a pretty satisfactory surrogate.

Some Important Ingredients

Fish

Although Nice has never been a major fishing port like Marseilles or Ste, fish, not meat, has always formed the staple diet of its inhabitants. There is an old Niois saying which goes: Fish are born in water and die in oil. It is well worth visiting one of the colourful fish markets in Nice or in one of the neighbouring towns along the coast. Imposing fishwives, known as rptira in Niois, set the streets ringing with their cries of O pe! O pe! (Fish for sale! Fish for sale!).

In February, you are more likely to hear A la bella poutina! A la bella poutina!, when their barrows are laden with glistening poutine (anchovies and sardines in their larval state). The fishing of these tiny creatures (several hundred to the pound) is prohibited elsewhere in France. But it was decided in 1860, when the Comt de Nice was incorporated into France, to introduce special legislation permitting such fishing between Antibes and the Italian border. Legend has it that Empress Eugnie, who apparently liked to call the fishermen of Nice her good friends, had something to do with that decision. The fishing of poutine (recipes 117 and 118) is nowadays very strictly controlled: no boat may make a catch of more than 100 kg, and the authorized period is closed by the maritime authorities as soon as the fish begin to grow scales.

Next page