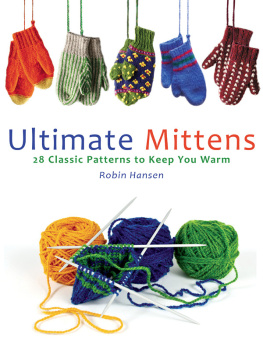

Copyright 2011 by Robin Hansen

Photographs Heather Perry

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-0-89272-975-3

Design by Chilton Creative

Printed in China

54321

Distributed to the trade by National Book Network

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data available upon request

In Memory of Elizabeth Zimmermann who helped us understand the process and logic of knitting

For Nora Johnson who opened my door to Maines traditional knitting

For my daughter Hanne Orm Tierney who carries traditional knitting into the future

Acknowledgements

The debts of anyone working in traditional handcrafts mount up quickly. Everything I havent figured out myself, and even some of that, started with something a real person told me or showed me or with a book written or photographed by a friend, who thereby told me or showed me.

Thanks to Nora Johnson for teaching me how to knit with two colors without getting all tangled up, for giving me my first three traditional mitten patterns, for insisting that I do it right, and for showing me the pull-up in striped mittens, although she didnt call it that.

Thanks to Mary A. Chase for giving me access to her excellently catalogued and preserved collection of traditional European and Maine mittens and gloves, particularly for the Double-Knit Fishermans Mitten knitted by her husbands relative, Iantha Blake, and for the Polish Twined Basket Mitten.

I thank Birgitta Dandanell for being a friend and for introducing me to Swedish twined knitting, to Torbjrg Gauslaas work with twined knitting in Norway, to Mary A. Chase and the Double-Knit Fishermans Wet Mitten.

I thank the late Torbjrg Gauslaa, who taught me twined knitting and the spit splice and, without meeting or knowing me at all, invited me to spend a week in her home learning about twined knitting. Some of the photographs of twined knitting are of her demonstration samples.

I thank Kate Martinson for correcting my perception of Torbjrgs spit splice and Eva Trotzig for introducing me to the ideas that literacy doesnt equal intelligence and that illiterate knitters have much to offer us.

Elizabeth Zimmermann Ah, difficult! Where to begin? Her percentage concept of sweater pattern design revolutionized my knitting and in this book is the basis for my system of proportional mitten sizes. Many of her nifty little unventions are incorporated consciously and unconsciously in every pattern I write and knit. She is deeply missed. Thank you, and good-bye, dear Elizabeth.

Thanks to Meg Swanson for years of encouragement to write about traditional knitting, and for the technology of her upside down I-cord gloves.

I thank Ann Feitelson and her Shetland Islands source Elizabeth Johnston for a wonderful old-time Shetland mitten, here called Shetland Ladders, and for permission to use it in this book. Thanks to luva Hsgar and Nicolina Jensen in Trshavn for teaching me about Faroese knitting and helping me to understand its importance in the Faroe Islands.

Thanks to Sarah Miller for her Windblock Mittens and their directions, which she gave me almost as they are printed here so that she could stop self-publishing them. A great addition to this collection.

I thank Briggs & Little employees Bernette Saunders and Patricia Gass for developing the Hearty Alternative Stuffed Mittens based on an article I wrote, and Jeannie Wild, somewhere in Canada, for her information on the expression and custom of giving him the mitten.

Alice Devine, Marie Litterer, Jenifer Hegarty, Adrienne DOlimpio, and Alice Stewart kindly test-knitted mittens, trying out the patterns for clarity and providing useful critique. Becky Chapman, Holly Richards, Arlena Flick, Ann Tomes, Gerry Cosgrove, and Julia Bavers actually paid money to learn to make Polish Twined Basket mittens at Halcyon Yarn in Bath, Maine, thereby testing my directions. A similar workshop tested the directions for Afghan gloves but produced mittens. Thank you all!

Bartlettyarns in Harmony, Maine, Nordic Fiber Arts in Durham, New Hampshire, and Green Mountain Spinnery in Putney, Vermont, kindly provided yarn to knit the samples. Thank you, Russ, Debbie, Claire!

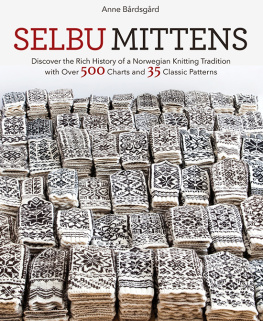

I fling to the four winds thanks to unknown knitters in Newfoundland, Kennebunk and Bath, Maine, Norway, the Faroe Islands, Afghanistan, Nepal, Sweden, and Shetland for Rickrack stripes, Secret Fleece, Thumbies Plain and Simple, Eyunstovu Slants, Kennebunk Woolly Bears, and the rest. And to the women long past in Aroostook County Maine, northern Canada, and Poland who developed Inuit/Aroostook Sewn Mittens and Polish Twined Basket Mittens. Thanks to the Inuit women who, through their handwork, taught me about the proportions of hands and how to make leather mittens that fit.

Thanks to Down East Books and editor Michael Steere in particular for their patience in waiting for me to finish this manuscript. Thanks upon thanks to my husband Erik for helping me with the engineering of mittens, for teaching me how to find delta, which for him means one thing but for me means how many stitches to increase, take off for a thumb, and cast on over the thumb hole, for editing and checking my math and for his gentle patience as I struggled (and struggled) to finish and to limit this book. I like you the way you used to be, he told me. Before you were on deadline.

Introducing Folk Mittens

So many ways to make a simple thing like a mitten! Nora Johnson exclaimed one day when I had brought her my umpty-umpth exciting, newly discovered old-time mitten. Nora is gone now. She died in her late nineties, but was until her death a constant support and inspiration on my hunt for old-time Maine mittens.

What she said is true, but more than true, because thats the way of folk handcraft: It flows through human hands and minds, from one person to the next. It cant exist without a person, and each person adds to or subtracts from the way its done to make the product her own.

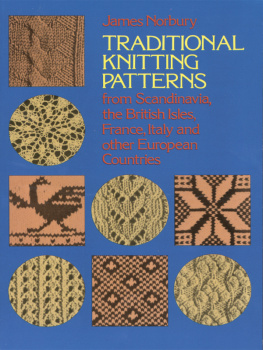

The United States has had a major dose of worldwide folkknitting techniques in the past forty years, starting with Aran sweaters and ending, for now, with Bosnian socks. Weve learned about Latvian mittens, Andean caps and ski masks, Cowichan sweaters and Swedish twined knitted sleeves. But you dont find many of these items in use as they arrived on our shores. We adapt. We play.

That Bosnian socks dont fit well into shoes doesnt matter if the tradition isnt your own and you want a pair. Add a round heel, a Kitchener stitched toe and youve got a dandy boot or ski sock. Aran sweaters too warm for the office? Knit one in cotton, knit one in a light sportweight yarn, and its fine indoorsan American aran (small a).

So it is with mittens, and perhaps more so, because mittens are hardly more than a swatch with a thumb. Their small format makes them ideal canvases for learning new techniques, playing with colors, or using fun techniques considered too laborious for larger garments.

So while Nora is entirely right, that there are so many ways to make a mitten, there are, in fact, daily, new ways to make a mitten or a glove to perform any number of roles. Tradition is never static, and folk traditions live only as long as people adapt them to their tastes and needs. Women who change and play with these designs arent reviving them, nor are they violating tradition. Theyre participating in tradition and carrying it forward.

Even within folk tradition, there are inventions, fashions, shifts. The addition of the cuff to mittens in the last century is an example of folk innovation: the cuffs, called wristers, used to be separate, and mittens often had a thick band of pile called a wind-stopper to keep wind out of the sleeves (which also had no cuffs). The colors of Maine and Canadian folk mittens of the 1940s and fifties were garish, to be easy to see in the snow (Im told). Those of the 1960s through the eighties were either subtle heather wools or harshly colored acrylics. The 1990s loved bright tweedy colors. Today, we play with bright solids in unusual combinations. The theme doesnt change, but the particulars do, constantly.