ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Charlie Seemann is the executive director emeritus of the Western Folklife Center in Elko, Nevada. He holds an MA in folklife studies from the University of California at Los Angeles. He was an instructor in folklore and folk music at Moorpark College in California for six years, and then he worked as a folklorist and director of the Western Regional Folklife Festival for the National Park Service/Golden Gate National Recreation Area in San Francisco until 1981. He then moved to Nashville, Tennessee, where he was deputy director at the Country Music Foundation/Country Music Hall of Fame for twelve years. He served as program director of the Fund for Folk Culture in Santa Fe, New Mexico, before assuming the executive director position at the Western Folklife Center in 1998. He retired in 2014.

A T W O D O T B O O K

An imprint and registered trademark of Rowman & Littlefield

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2016 by Charles H. Seemann, Jr.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN 978-1-4930-2231-1 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-4930-2232-8 (e-book)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

PREFACE

There are many great western musicians active today, some of whom might be called singing cowboys because they perform cowboy or western music, and then there are cowboys who sing. I once asked the late Glenn Ohrlin what he thought made a good cowboy singer. He answered, First, you gotta see how good they can ride. That is the premise on which I have based this book. My intention is not to make value judgments, but simply to look at a segment of the cowboy and western music scene that has an occupational grounding. That is, music made and performed by men and women who are, or have been, working cowboys, ranchers, packers, and horse trainers, or who have deep roots in cowboy and ranching culture that have shaped and informed their music. There has been a proliferation of western music performers since the renaissance of interest in cowboy music, poetry, crafts, and culture in the mid-1980s by events like the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering, in Elko, Nevada. The people included here are, for the most part, folks who I have had the good fortune to get to know and work with over the past forty years, and a good deal of the information in these profiles comes from interviews I conducted with them. This list is by no means complete or exhaustive; there is no way it could be. I know there are, undoubtedly, many more people out there who could and ought to be included, and to those individuals, I apologize. Omission reflects only the limits of space, time, and my personal knowledge.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

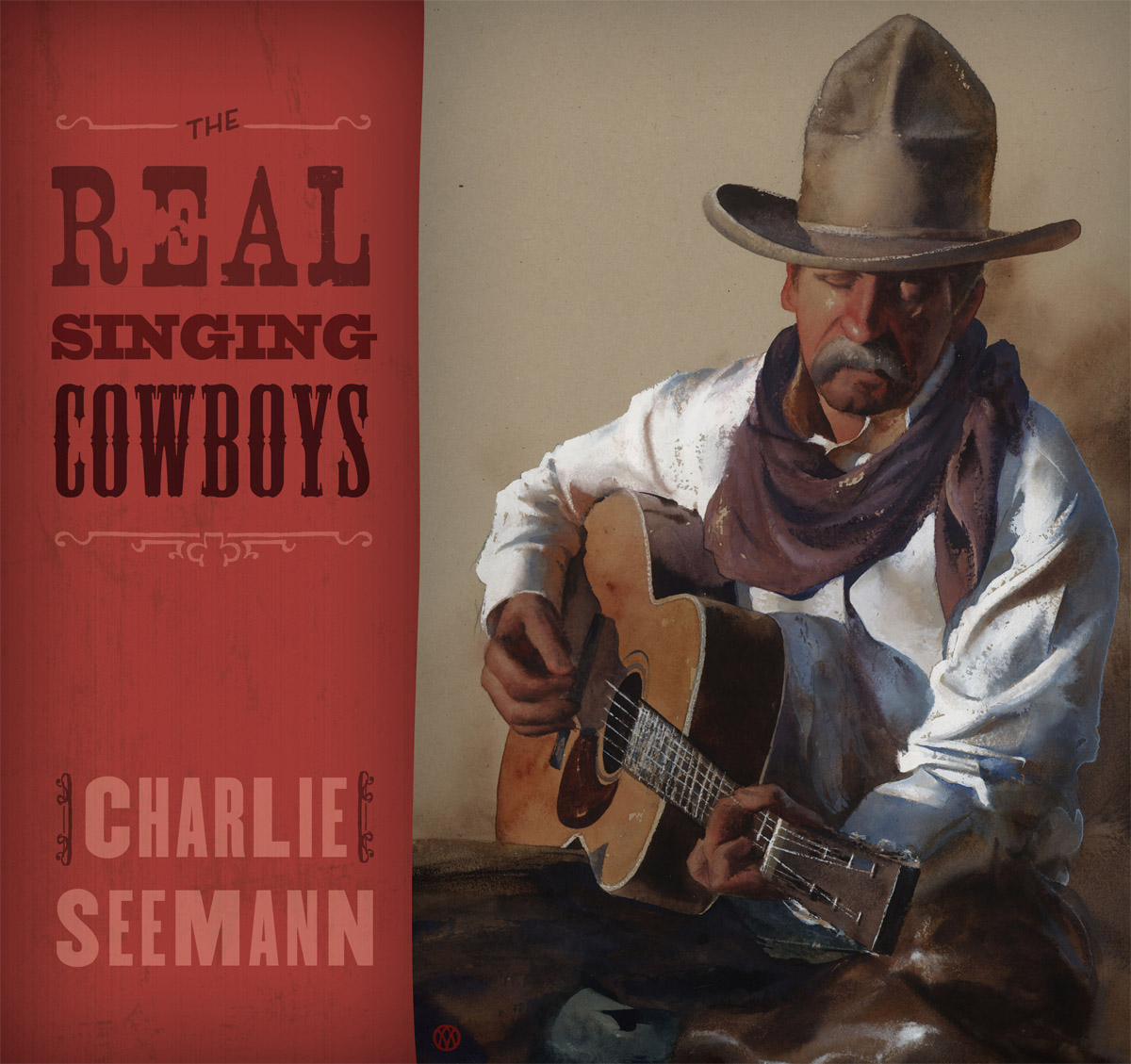

There are a number of people whose assistance, generosity, and encouragement I wish to acknowledge. First, of course, are all the singers who have continued and built upon western musical traditions. While many artists and family members provided photos, thanks are due to the many photographers who generously who contributed their original work: Steve Atkinson, Natalie Brown Baca, Patricia Brewer, Becki Burson, S. J. Dahlstrom, Diane Dalton, Sheri Davis, Zane Davis, Jennifer Denison and Western Horseman magazine, Charlie Ekburg, Marie Geibel, Guy Gillette, Lynn Martin Graton, Steve Green, Lee Gunderson, Coleen Gustafson, Ross Hecox and Western Horseman magazine, Bruce Hucko, Bob Kisken, Mark LaRowe, Jessica Brandi Lifland, Jens Lund, Kevin Martini-Fuller, Mindy Miller, Mary Mumma, Tony Parker, Roberta Parson, Rick Philip, Tom Pich, John Michael Reedy, Kent Reeves, Bill Rey, Chris Simon, Larry Walker, Patty Wands, Bill Watts, Sanne Lykkegarrd Wiesneck, and Ann L.Wilson. Several organizations also shared photos: Stacey Cramer-Moore and the Campfires, Cattle & Cowboys Gathering, Jody Lake and the Dee Events Center, and Western Horseman magazine. A huge shout-out to archivist Steve Green of the Western Folklife Center for his assistance in locating and selecting photos from the centers extensive collections. I want to thank artist Wily Matthews for the use of his painting for the cover.

I want to thank my longtime friend and colleague Patricia Hall for encouraging me to proceed with this project and poet Paul Zarzyski for being a great sounding board and providing sage advice. Thanks, too, to my literary agent Rita Rosenkranz and the great folks at Rowman & Littlefield: Erin Turner and Courtney Oppel. Finally, thanks to Katherine Hearon for her invaluable proofreading of the text. Any errors or admissions are strictly my own.

INTRODUCTION

The cowboy is the quintessential American hero, representing the values we Americans purport to hold dear: independence, honesty, hardiness, and self-reliance. The once lowly common laborer on horseback from the trail drive days of the 1800s has been transformed into a mythical icon. He has loomed large in our popular culture, literature, motion pictures, and music. But the cowboys of the silver screen and the Nashville recording studio have little in common with the men and women of the rural West who still make their living with horses and cattle on the land. There are, among these ranching folks, authentic cowboys and cowgirls still continuing cowboy song and musical traditions, not only performing the great old cowboy classics, but writing fresh, literate, new songs reflecting their lives on the land today. These are the people you will meet in this book.

Cowboy songs originated as the occupational folk songs of working cowboys, in the same way that songs of sailors, loggers, and miners developed in those occupations. People working in isolation and perilous conditions, left to their own creativity to entertain themselves, have always created songs and poems. Those songs reflected the often-harsh realities of the life and work of the cowboys, from the dangerous work with horses and cattle to the living conditions on the trail and in the cow camps. The cowboys also sang nonoccupational songs that dealt with other aspects of the western experience, such as immigration, outlaws, and Indians, along with popular songs of the day.

Many traditional cowboy songs were reworkings of folk and popular songs from the British Isles. For example, The Streets of Laredo was a cowboy version of a British and Irish broadside ballad, The Unfortunate Rake. Likewise, Bury Me Not on the Lone Prairie came from an old sailors song, The Ocean Burial. Working cowboys also made up new songs out on the range, often setting the words to familiar traditional or popular melodies. The borrowing of older tunes and the reworking of lyrics to fit a new environment is a time-honored way of creating new songs. These ranged from anonymous folk songs like The Old Chisholm Trail, with verses added by many different people over time, to classic compositions such as When the Works All Done This Fall, written by Montana cowboy poet D. J. OMalley in 1893, and originally set to the melody of Charles K. Harriss popular Tin Pan Alley song of 1892, After the Ball.

By the end of the 1800s, the days of the long trail drives that gave rise to cowboy songs were mostly over. With the advent of the railroads after the Civil War and the invention of barbed wire in 1874, the open range began to give way to perimeter ranches fenced with the Devils hatband. Cattle and cowboys no longer moved as freely across the open landscape of the West, and the cowboys work changed accordingly. Rather than spending weeks and months on trail drives, he now lived part of the time in bunkhouses or cow camps and fixed fences as he tended the cattle. In this environment a rich new body of cowboy poetry and music was created. It was difficult for cowboys to carry instruments on trail drives, and most singing was unaccompanied, although smaller instruments like harmonicas and Jews harps were common, and a fiddle could be carried in a bedroll. Bunkhouse culture provided a time and place for the guitar, mandolin, and banjo, and some of the best and well-known traditional cowboy songs come from this ranch period, such as California cowboy Curley Fletchers The Strawberry Roan and Arizonian Gail I. Gardners The Moonshine Steer.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.