This book has been something of a journey for me. Through its pages, I have relived many of my early fishing memories and dredged up names and faces from the distant past that I thought I had long forgotten.

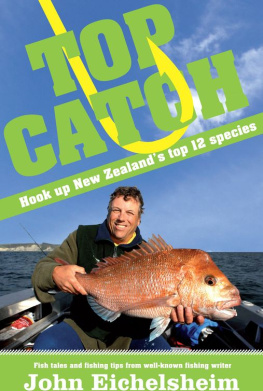

The idea wasnt my own. Publisher Random House put the concept to me through my editor, Sarah Ell. I could see it had some merit and agreed to give it a go, though it took some juggling to eventually decide on which 12 species to feature. To be honest, the list is arbitrary, based as much on which species are popular with the New Zealand public, as it was a list of my personal favourites, though Ive enjoyed catching every one. Its also a bit of a cheat here and there: there are two species of trout, three of salmon, halfa-dozen of tuna and three species of marlin in New Zealand. Ive grouped them together under the chapter headings trout, salmon, tuna and marlin for simplicitys sake.

Some fish were chosen because most of the anglers I know dream of catching them: marlin, tuna, salmon and maybe even kingfish fall into this category. Others were chosen because they are the fish we Kiwis like to catch. Many great angling species were left off. Perhaps theyll make the cut next time

As I worked through my list I was struck by how lucky we Kiwis are to have so much good fishing on our doorstep. I sometimes think we take it for granted, which we shouldnt, because it is very precious.

Harking back to an earlier time when I fished for blue cod, tarakihi and trout on a regular basis has served to remind me how much I used to enjoy catching them.

When I moved north nearly 30 years ago, my fishing horizons changed with the geography. Snapper, kingfish and game species such as tuna and marlin became my focus. In most respects Im like every other Kiwi angler: I fish for what I can find close to home. In the Hauraki Gulf, thats snapper, kingfish, trevally and kahawai. Anything else is a bonus.

Thats inevitable, I guess, but writing this book has made me realise how much I miss some of those other great fish I used to catch and has made me determined to make time to fish for them once more.

Ive been luckier than most: 20 years working as a fishing and boating writer/editor means Ive enjoyed a range of fishing opportunities most people never experience in a lifetime. Despite years of exile in Auckland, Ive travelled and fished around New Zealand on a regular basis, allowing me to reacquaint myself with old friends, both human and fish, on a regular basis.

So in some respects Im well qualified to write this book: Ive caught most of the fish species available to New Zealanders up and down the country and all of those that feature in these pages with the exception of black marlin.

This book is not meant to be a comprehensive guide to catching every fish featured, though theres plenty of advice on tackle and techniques. Theres also some useful information on their distribution and ecology.

Its more a celebration of the great sport fish we can enjoy in New Zealand and an opportunity for me to share some of the excitement and joy I have experienced fishing for them. With a bit of luck, this book will inspire readers to fish for them too, and perhaps by reading it, theyll learn a thing or two about 12 of New Zealands favourite fish.

John Eichelsheim

Auckland, May 2010

During the 1970s snapper were not overly common in Wellington Harbour and certainly didnt figure in the catches of a small boy restricted to occasional mornings fishing from the wharf at Petone or Days Bay.

A couple of seasons worth of unrestricted commercial fishing for spawning snapper in the early 1970s had totally destroyed the regions snapper stocks, as it had in Golden Bay; it has taken until the present day for them to partially recover. A few commercial fishermen got rich during the snapper boom, but the rest of us were left much the poorer.

As boys our sights were set on humbler fish we could tackle with hand lines and hooks wed begged, borrowed and found. The gear was simple: a length of nylon line we considered ourselves too modern for the green linen cord lines the old blokes used wound onto a plastic or glass bottle filled with fine gravel. Large Coke bottles were popular because their flared bases and voluptuous curves made them ideal for casting: hold the bottle by its neck with the base pointed in the direction you want the line to go, twirl the sinker and bait around your head and let rip. The sinker would fly through the air, pulling coils of nylon from the bottle just like a spinning reel. We could achieve respectable casts this way with minimal tangles.

Although, like most kids, I started fishing for cockabullies and spotties, by the time I was 11 or 12 years old these tiddlers no longer held the same attraction. Id set my sights on the occasional kahawai, barracouta or red cod that frequented the wharves I fished.

Kahawai were the glamour fish. We used baits of whole herring (yellow-eyed mullet) when we could get them, fished alive or dead. Otherwise it was whole spotties or strip baits cut from whatever fish we could catch. Store-bought bait was rare and much less generally available than today. Some dairies carried small boxes of trevally and squid, but we caught our own baits, often scrambling onto the cross-members beneath the wharf to gather mussels and access the bait schools that congregated there. Stale bread would usually attract herrings and bread paste on a small hook would catch them. Either that or a large weighted treble hook used to jag them!

To be honest, catching bait was as much fun as fishing for kahawai, although not without danger. Resting seals were regular occupants of under-wharf platforms and cross-members during winter. They were not always amenable to sharing their space with small boys and a bad-tempered seal could evict us from the wharf altogether. At other times they were happy to tolerate us at close quarters.

Ill never forget their stench, or the way the oil from their coats (probably mixed with urine if I think about it) would get into our clothes as we clambered around under the wharf. It had a very distinctive odour and was, my mother told me, impossible to wash from my clothes.

A Sunday morning indelibly etched in my memory kindled a love affair with snapper that remains to this day. It began like many others. My long-suffering mother dropped my mate Ian and me at Days Bay Wharf after early Mass. We clutched our tackle bags, a lunch box and half a loaf of stale bread. She never took too much notice of my dont pick me up until dark plea, but I was reasonably confident wed get to spend most of the day fishing.

Bait fishing that morning was poor. Try as we might, we couldnt lure any herrings close enough to catch, and there was nothing under the wharf. Fearing Id miss out on the best fishing of the day, I settled for a small spotty I caught near the wharf piles while Ian persevered with herring fishing.

Spotty is not brilliant bait, at least for kahawai, which was what I hoped to catch. I had caught the odd barracouta on it, but seldom kahawai, so I was somewhat surprised when my plastic Vim bottle began to rattle and jump just a few minutes after Id tossed the unweighted spotty as far out into the bay as I could.

Picking up the line, I let it slip steadily through my fingers before taking a deep breath, tightening up and striking with the typically exaggerated arm movement of hand line fishers. If the timings right, more often than not the reward is solid resistance and a strong pull on the line. If the gods are smiling, a fat kahawai will leap out of the water and a very excited boy will pull it in hand over hand as hard and fast as the line and his courage will allow.

But this time there was no leap, and while there was solid resistance, there was none of the zipping around Id come to expect from kahawai. Hauling on the line, I made little impact on the fish at first, the line cutting deep into my index finger and drawing blood. Conscious of the number and dubious quality of the knots joining my composite line together, I eased off a little, retrieving line only when the fish allowed me to.