To all those people who not only enjoy Montanas rivers but also work to conserve them.

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Blvd., Ste. 200

Lanham, MD 20706

www.rowman.com

Falcon and FalconGuides are registered trademarks and Make Adventure Your Story is a trademark of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2021 The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

A previous edition of this book was published by FalconGuides in 2008 and 2015.

Original text incorporated from A Floaters Guide to Montana, written by Hank and Carol Fischer, 1979

All photos by Kit Fischer unless otherwise noted

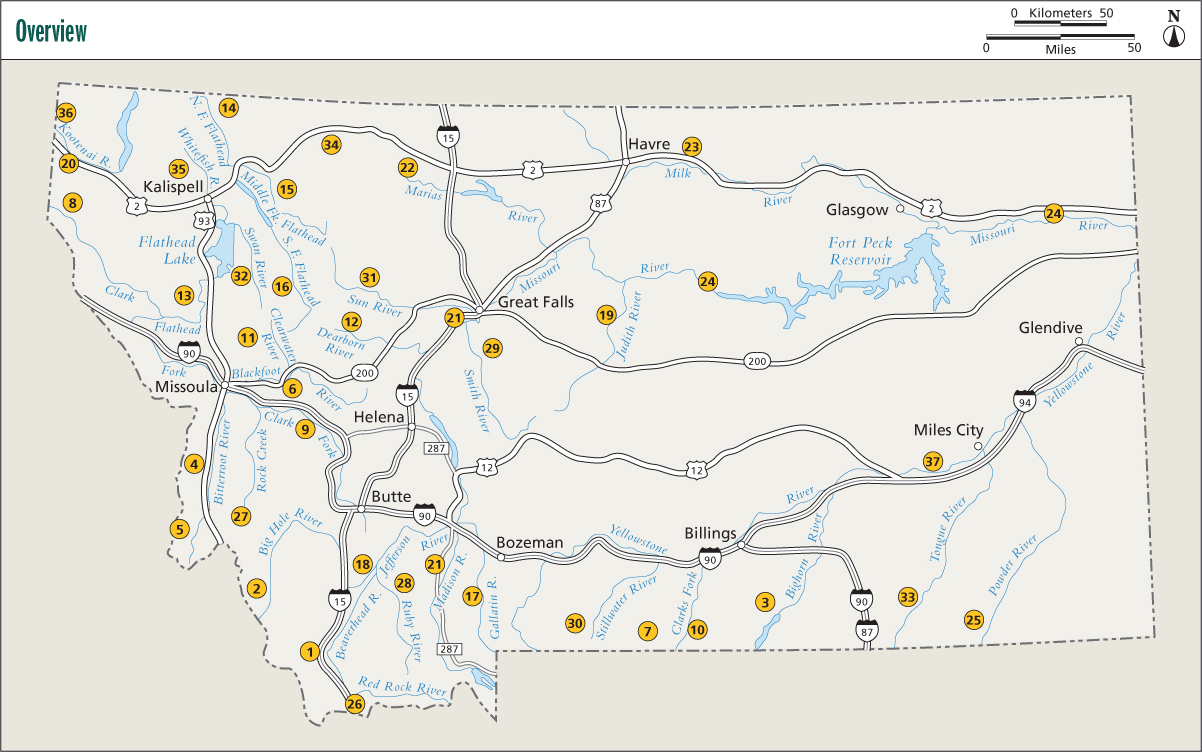

Maps by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN 978-1-4930-5970-6 (paper: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4930-5971-3 (electronic)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The author and The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. assume no liability for accidents happening to, or injuries sustained by, readers who engage in the activities described in this book.

Guide

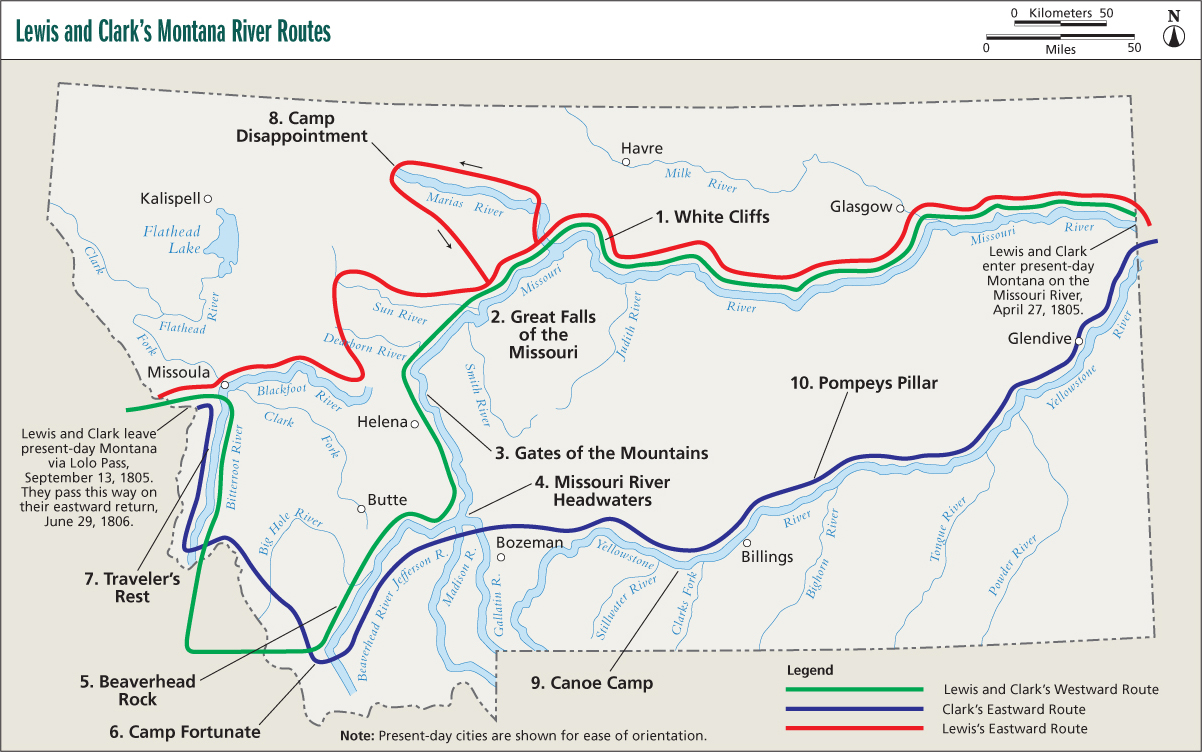

These dates and events correspond to the labeled sites on the map on the preceding page. The map shows the routes Lewis and Clark followed on several Montana rivers on their way west and on their eastward return.

- White Cliffs, May 31, 1805A spectacular 35-mile section of the Missouri River, described by Captain Lewis in a journal entry as resembling a thousand grotesque figures.

- Great Falls of the Missouri, June 21July 15, 1805Termed a sublimely grand spectacle by Lewis; it took the Corps of Discovery nearly a month to make the 18-mile portage.

- Gates of the Mountains, July 18, 1805Lewis said this place had the most remarkable cliffs the expedition had seen to that point. These clifts rise from the waters edge on either side perpendicularly to the height of 1200 feet. Every object here wears a dark and gloomy aspect. The tow(er)ing and projecting rocks in many places seem ready to tumble on us. A boat-tour excursion carries modern-day visitors to the site.

- Missouri River Headwaters, July 2729, 1805Lewis described the place where the Jefferson, Madison, and, a short distance upstream, the Gallatin Rivers merge as an essential point in the geography of the western world.

- Beaverhead Rock, August 8, 1805Sacagawea recognized this landmark, which resembles a swimming beaver, and knew her tribe, the Shoshones, would not be far away.

- Camp Fortunate, August 17, 1805Sacagawea found the Shoshones here, and they provided horses for the Corps trip over the mountains.

- Travelers Rest, September 910, 1805; June 30July 2, 1806The Corps of Discovery rested here in preparation for what turned out to be an arduous passage over the mountains. On their return trip the expedition camped here again and separated into two parties. Lewis headed for the Blackfoot River; Clark led his party down the Bitterroot River.

- Camp Disappointment, July 2225, 1806The northernmost point reached by Lewis on an exploration of the Marias River; this is close to the spot where Lewis and his party had a hostile encounter with Blackfeet Indians. Two braves were killed.

- Canoe Camp, July 1923, 1806Clark and his men built two canoes at this site for their return down the Yellowstone River.

- Pompeys Pillar, July 25, 1806Named for Sacagaweas son, this sandstone pillar holds the only physical evidence of Lewis and Clarks passage through Montana: Clarks name and the date carved into the rock.

By such a river it is impossible to believe that one will ever be tired or old. Every sense applauds it. Taste it, feel its chill on the teeth: it is purity absolute. Watch its racing current, its steady renewal of force: it is transient and eternal. And listen again to its sounds: get far enough away so that the noise of falling tons of water does not stun the ears, and hear how much is going on underneatha whole symphony of smaller sounds, hiss and splash and gurgle, the small talk of side channels, the whisper of blown and scattered spray gathering itself and beginning to flow again, secret and irresistible, among the wet rocks.

Wallace Stegner, The Sound of Mountain Water

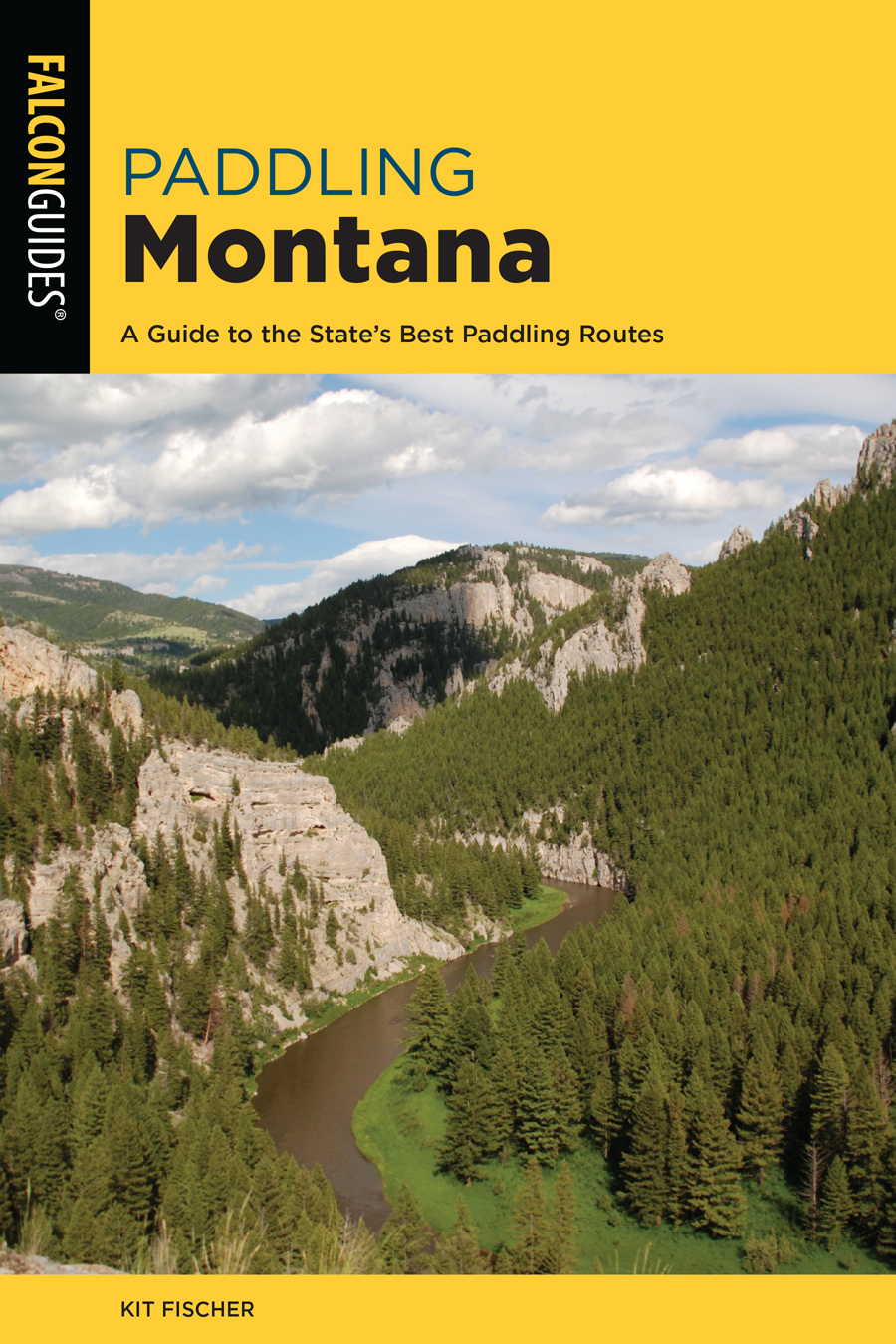

Most people carry an escape dream, an idyllic plan for the time when life becomes too harried or complicated. For some the dream takes them on a long wilderness trek. Others hope to sail off to sea. For many the fantasy is simpler: Put a canoe, kayak, or raft in the nearest river, lie back, let the sun warm the body, trail a hand in the water, and drift away. With over 20,000 miles of streams in Montana, a lifetime of exploring can be had without ever leaving the state.

Its a dream that started with the excursions of early river explorers like Lewis and Clark and John Wesley Powell. It has been kept alive by writers like Mark Twain, Ernest Hemingway, and Bernard DeVoto, and now it is being relived by modern-day river runners.

Montanas rivers have a special kind of historical significance, as the waterways played a key role in the Treasure States early development. In early times the rivers carried only Indians and intrepid explorers. Later they brought miners, loggers, cowboys, sodbusters, soldiers, and shopkeepers. Indian bullboats and French pirogues were gradually replaced by flatboats and even steamships. It was only with the coming of the railroads in the late 1800s that Montanas rivers faded in importance.

One reason the rivers were so important is that they are easily navigated. Despite the cold waters and rapid flow, most Montana rivers can be floated by people with only moderate river skills. Those who have seen Montanas towering mountains often find this hard to believe, as did Meriwether Lewis of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. He noted in his journal of 1805:

I can scarcely form an idea of a river running to great extent through such a rough mountainous country without having its stream intersepted by some difficult and dangerous rappids or falls, we daily pass a great number of small rappids or riffles which descend one to or 3 feet in 150 yards but we are rarely incommoded with fixed or standing rocks and altho strong rapid water are nevertheless quite practicable & by no means dangerous.

The majority of Montanas rivers lie in the mountainous western portion of the state, where they flow down broad valleys between mountain ranges. In arid eastern Montana, where only a few major rivers flow, the streams are generally broad and flat as they cut through open grassland and sagebrush country. While the sparkling western streams may be more spectacular, the eastern rivers have a quiet beauty and offer better opportunities for solitude.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.