For Mum and Dad, for everything.

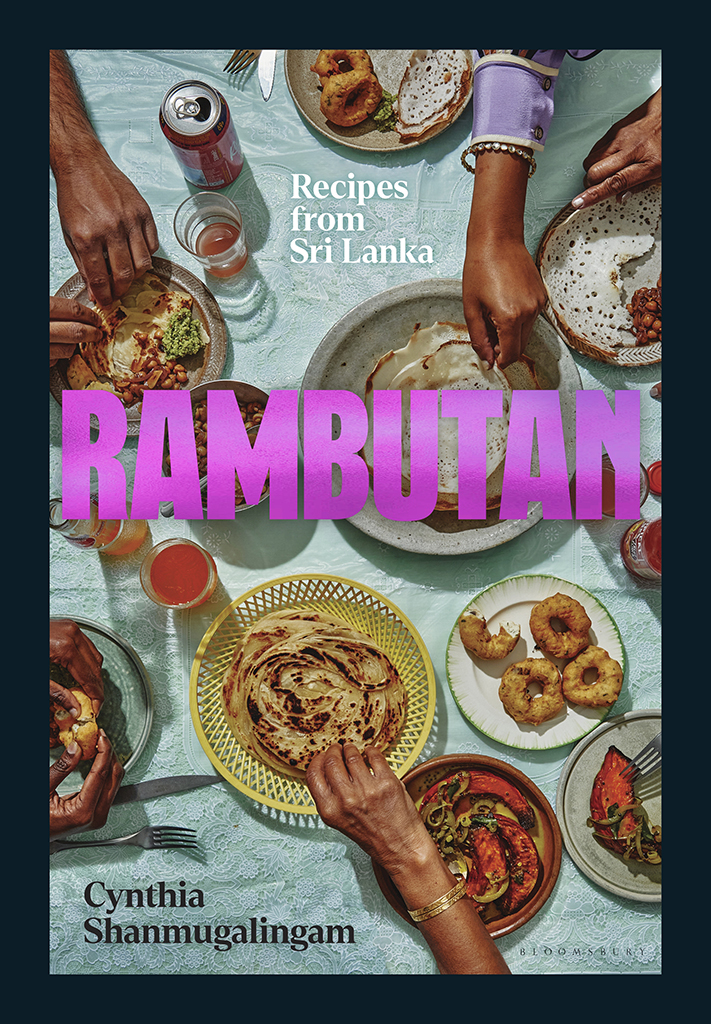

At the top of Point Pedro market, a few miles on a noisy bus from my parents house at the northern tip of Sri Lanka, you will find a whole storey of vegetable sellers. In the large, airy building, some feet away from the black and gold sand, you can still hear the Arabian Sea, ferocious with fish, crabs and catamarans. Beside the shouting in the fish market and above the rice guy with his nineteen different kinds of rice, the vegetable sellers sit cross-legged on a cement floor. Each one is surrounded by beautiful piles of fruit and veg, with slightly different specialisms and prices. When you walk past the okra guy, he says yes! okra? in Tamil as if you had asked him a question. And if you glance at him in response, he starts snapping the ends off his okra with a serene smile on his face.

The first time I saw this I was like, dude what are you doing? And my mum started giggling. Snapping okra this way demonstrates how fresh it is, she explained to me. Fresh okra should not be soggy or soft. It has a taut body and it will snap clean.

This is the kind of cooking knowhow that Mum alongside almost everyone else in my Sri Lankan family has always seemed to just know. Like all the great cooks from the island, they tend to prod, sniff, shake and listen to their ingredients with the kind of concerned familiarity of a chiropractor. They seem to have been born knowing just what fruit, veg, fish, meat, spices and rice to buy, when everything is in season, and how to turn it all into the wonderful Sri Lankan fare that they eat every day.

Unlike them, I have had to learn a different way. When my parents left the island in the 1960s to live in England, they didnt know that on the flight, thousands of years of culinary knowledge would be evaporated into thin air. Alongside my brother and sister, I could never quite pick up everything they knew back home, no matter how many withering looks my father gives me when he asks me to go over to that vendor to pick out a pumpkin, and I return with a shit one.

And yet, I have learned how to make Sri Lankan food that is both exciting and rewarding, and I know that by the end of this book, you will too.

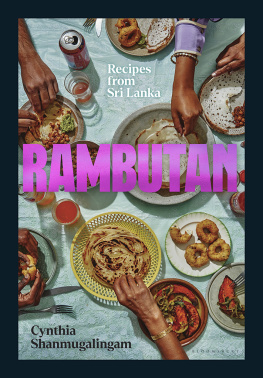

Rambutanis the story of an immigrant kid in England trying to cook her way out of the profound sense of loss about the place her parents called home. It contains the best recipes from my mum, grandmother and all the other generous aunties and friends who gave them to me, sometimes modified a little to make them easier, or because they seemed more fun that way, but always retaining the ancient spirit of Sri Lankan cuisine.

Like Point Pedro market, this book is led by delicious fruit and vegetables, and half the recipes are vegan (see page 333 for a full list of the vegan and vegetarian recipes in the book). There are one or two rules that require a little effort, but the recipes are designed to deliver as much edible Sri Lankan joy as easily as possible. And at the same time, Rambutanis about my sense of the island, pieced together through a lifetime of travels, myths and memories.

________

Warning:I have not shied away from the countrys often painful history of war, colonial oppression, slavery, spice trading, poverty and proselytising in these pages. These chapters, too, are part of the story of our food. Rather than dimming the ingenuity and creativity of the islands cooks, in successive generations our ancestors created Sri Lankas culinary songbook. They combined the Javanese, Malay, Indian, Arab, Portuguese, African, Dutch and British influences that came into the island with Tamil, Sinhalese and indigenous cooking. Using both ingredients native to the island (like cinnamon, curry leaves and cassava) as well as ingredients brought in by its visitors (like chillies, tomatoes and cashew nuts), the result has been a delicious, unique food tradition that is completely our own, and if I do say so myself one of the worlds most unsung cuisines.

Today, a Sri Lankan table might include: crispy bowl-shaped hopper pancakes made of fermented rice and coconut milk, or fresh sambols made with green mango, raw carrots, or bright green chillies. There might be spicy red curries of roast aubergine or braised breadfruit cooked in coconut milk and smoky spices. There could be black curries, like pineapple or pork, cooked with toasted coconut, sugar and vinegar. There might be pillowy, crispy rotis; flaky, folded