Copyright 2023 by Maya Feller

Photographs copyright 2023 by Christine Han

Published in the United States by Rodale Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

RodaleBooks.com

RandomHouseBooks.com

RODALE and the Plant colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Feller, Maya, author. Title: Eating from our roots / Maya Feller, MS, RD, CDN. Description: First edition. | New York : Goop Press/Rodale, [2023] | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2022016808 (print) | LCCN 2022016809 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593235089 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593235096 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: International cooking. | Cooking (Natural foods) | LCGFT: Cookbooks. Classification: LCC TX725.A1 F4135 2023 (print) | LCC TX725.A1 (ebook) | DDC 641.59dc23/eng/20220628 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022016808

LC ebook record available at https://lccnloc.gov/2022016809

ISBN9780593235089

Ebook ISBN9780593235096

Photographer: Christine Han

Editor: Donna Leffredo

Print Designer: Mia Johnson

Production Editor: Serena Wang

Print Production Manager: Philip Leung

Print Compositor: Merri Ann Morrell and Zoe Tokushigue

Copy Editor: Natalie Blachere

Indexer: Jay Kreider

Marketer: Jamila Coleman and Odette Fleming

Publicist: Tammy Blake

Ebook Production Manager: Jessica Arnold

rhid_prh_6.0_142372159_c0_r0

INTRODUCTION

The first time I had sugarcane freshly cut from the stalk, I was around five years old. I remember sitting with my grandfather, Simeon Alexander, in Diego Martin, Trinidad, enveloped by warm air while being kissed by the sun, sucking on sugarcane, feeling safe, loved, and without a care in the world. We would take regular drives from Diego Martin up to the countryside of Toco to visit aunties, uncles, and cousins. Somewhere along the long winding narrow roads we would stop at a stand to enjoy a hot cup of soup, always served in a Styrofoam bowl, and roasted corn wrapped in foil. Id enjoy every bite knowing that when we arrived the aunties would have made coconut bake, dumplings, salt fish, pelau, cassava pone, bene balls, sour cherries, and so much more.

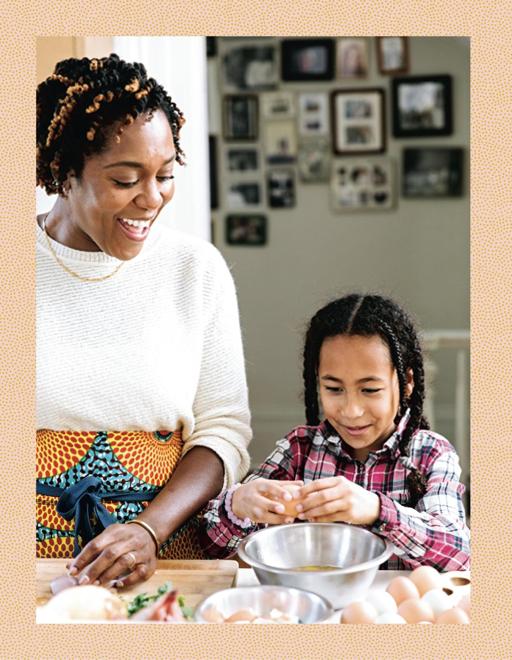

Many of my early childhood memories transport me back to visits to my grandparents or gatherings at home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where I grew up, with food, activism, and community at the center. I stood by and watched family and friends come together to turn out the most succulent, flavor-filled dishes, truly the best foods I have ever tasted.

During visits back to Trinidad and Tobago, food was always abundant, offered without judgment, and most often made from scratch and always with great care. These home-cooked foods provided plenty of nutrients in the most tantalizing packages. A food scientist would have dissected each dish and identified the plant-based dishes as phytonutrient- and antioxidant-rich, the poultry as free-range, and the eggs cage-free. To me and the members of my family, these foods were grown and harvested in traditional ways with methods that had been handed down over generations. The practice of growing, harvesting, and preparing food was done in a respectful way while taking the land and community into consideration. And mealtime was no different; the goal was to bring people to the table for nourishment.

My formative years were shaped with flavor, love, and curiosity. Every summer until I entered college we would travel the Caribbean, parts of western Africa, and later Australia. Instead of staying in hotels, we rented houses and spent weeks, sometimes months, living in communities with local peoplesshopping at the same grocery stores, visiting the same open-air markets, making friends with kids my age, and doing all the things that kids do. My mothers immersed our family in the local culture, and I integrated, made friends with local kids, and happily went along. As a child I never thought much about the experience of learning about culture through food and direct living with local people. It was only as an adult that I understood the imprint that was left on me as I experienced slivers of life throughout the African diaspora. Those experiences deeply shaped who I am and how I think about food and culture. To be clear, we all have culture, and culture is not something assigned only to racial and ethnic minorities. Each of us was born into groups that share similar values, social norms, and histories. It is these lived and inherited experiences that contribute to our cultural backgrounds.

My formative years were shaped with flavor, love, and curiosity.

I learned that when you walked into a persons home, you always greeted the parents, grandparents, and other family that may have been present with a good day and hug. If you were invited to a meal, you washed your hands and sat with the family, ate, then helped clean up. Family meals were the norm; food took time to prepare; a colorful plate, flavor, texture, and depth were given.

During high school, my family made a number of repeat visits to Treasure Beach, St. Elizabeth Parish, Jamaica, a seaside town that was not yet overrun by developers. At that time, the oceanfront was untouched. One of those summers, we spent my birthday there. I had made friends over time, so I knew this particular birthday would be a real fete. Meals were always central to a good party, and to celebrate I wanted curried goat, a favorite of mine from an early age. With the help of friends, one of my mothers organized the purchase of a whole goat, enough for a big party with many guests and mouths to feed. A neighbor organized a group of local fellows to prepare the goat, and a family friend organized the various cooks. Every part of the goat was utilized: the offal was used in manishwater , a kind of soup; the hide was dried to be used as a decorative rug; and the meat made enough curry for the whole community. It was a multigenerational gathering with joy at the center. So many celebrations were like this, with food and laughter in abundance.

After this trip I remember coming back to New York and wondering why there was such a disconnect between the foods that showed up on American plates and the origins of those foods. I was often struck by the desire to sanitize the appearance of food; skinless, boneless chicken breasts wrapped in cellophane, all perfectly uniform and placed within a food hierarchy that would be linked to a persons image of themselves.

Years later, I followed this thread and went to school to study clinical nutrition. I was interested in what happens to our bodies when we eat. I quickly learned that there was a set of well-researched food rules that were prescribed for people to follow in order to achieve healthy outcomesand the people in the communities where Id spent my childhood summers had those principles embedded in their traditional ways of eating. But something had gone awry with the way we eat in the United States.

Next page