Studies in the History and Culture of the Middle East

Edited by

Stefan Heidemann

Gottfried Hagen

Andreas Kaplony

Rudi Matthee

Kristina L. Richardson

Volume

ISBN 9783110740721

e-ISBN (PDF) 9783110740820

e-ISBN (EPUB) 9783110740974

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Note on Conventions

Transliteration

Transliterations from Arabic follow the guidelines of the International Journal of Middle East Studies.

Transliterations from Ancient South Arabian Languages follow the guidelines of P. Stein, Lehrbuch der sabischen Sprache I: Grammatik, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2013, 3840.

Transliterations from Ancient North Arabian Languages follow the system used by A. al-Jallad, An Outline of the Grammar of the Safaitic Inscriptions, Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2015.

Transliterations from Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek and Coptic follows the guidelines of P. H. Alexander, J. F. Kutsko, J. D. Ernest, Sh. Decker-Lucke and D. L. Petersen, eds., The SBL Handbook of Style, 2nd edition, Atlanta: SBL Press, 2014, 2530.

Transliterations from Middle Iranian languages follow the guidelines of W. B. Henning, Mitteliranisch, in: K. Hoffmann, W. B. Henning, H. W. Bailey, G. Morgenstierne and W. Lentz, Iranistik (Handbuch der Orientalistik 4, 1), Leiden: Brill, 1958, 20126, at 120126.

In order to increase the texts legibility, the names of Arab dynasties within the main body and footnotes have been written without diacritics (e.g., Abbasid instead of Abbsid). In the case of references to the Qurn/Qurnic, I have opted to exclude diacritics (Quran or Quranic).

Toponyms

I have used the current English nomenclature for well-known cities and place names. When specifying the provenance of documentary sources, I have used the standard Arabic name (e.g., Madnt al-Fayym, instead of Arsino). For the sake of convention, I use Nessana instead of Nan. In cases of multiple possible spellings, I have opted for the version of the name used in the Arabic Papyrology Database for papyri, and in the Thesaurus dpigraphie Islamique for inscriptions (e.g., al-Ushmnayn instead of al-Ashmnayn). For sources of unknown origin, I have indicated the geographical area (e.g., Egypt) to which they belong.

Editorial Conventions

For quotations from text editions the following system of abbreviations and brackets has been used:

r

recto

v

verso

ov

obverse

rv

reverse

fd

field

mg

margin

()

Round brackets enclose solutions of abbreviations

[]

Square brackets enclose text lost in a lacuna supplied by the editor

Double square brackets enclose erasures

< >

Angular brackets enclose text omitted in error by the writer

{ }

Curly brackets enclose text included in error by the writer

\ /

Diagonal strokes enclose interlinear text

References and Abbreviations

Citations from modern secondary literature follow the format of author-date. Abbreviations of editions and literary sources are discussed in a dedicated section in the bibliography (Abbreviations of Quoted Editions). Unless otherwise specified, the translations are my own. Abbreviations of titles of books of the Old and New Testament follow the guidelines of P. H. Alexander, J. F. Kutsko, J. D. Ernest, Sh. Decker-Lucke and D. L. Petersen, eds., The SBL Handbook of Style, 2nd edition, Atlanta: SBL Press, 2014, 7375. As has become commonplace, references to the Quran are abbreviated as Q Sura number: verse number (e.g., Q 1:1).

Languages and Scripts:

arab.

Arabic

aram.

Aramaic

CPA

Christian Palestinian Aramaic

JBA

Jewish Babylonian Aramaic

JPA

Jewish Palestinian Aramaic

bac.

Bactrian

copt.

Coptic

ENA

Epigraphic North Arabian

ESA

Epigraphic South Arabian

dem.

Demotic

eth.

Geez

gr.

Greek

lat.

Latin

MP

Middle Persian

syr.

Syriac

Dates and Calendars

Unless otherwise specified, dates are given according to the Common Era system ( ce ). Other chronological systems referenced in the text are:

| Islamic (hijr) Era ( ah ) | Day 1, year 1 = July 16, 622 ce |

| Era of Bosra ( eb ) | Day 1, year 1 = Mar. 22, 105 or 106 bce |

| Yazdgerd Era ( ay ) | Day 1, year 1 = June 16, 632 ce |

| Post-Yazdgerd Era ( pye ) | Day 1, year 1 = June 16, 652 ce |

| Bactrian Era ( be ) | Day 1, year 1 = Oct. 2, 223 ce |

Where relevant to the argument, I have used double dates, indicating the non-Common Era year followed by the Common Era year in round brackets, e.g., 77 ah (696/697).

Varia

Further terminological choices and concepts are explained in the dedicated section of the introduction (The Definitional Trap).

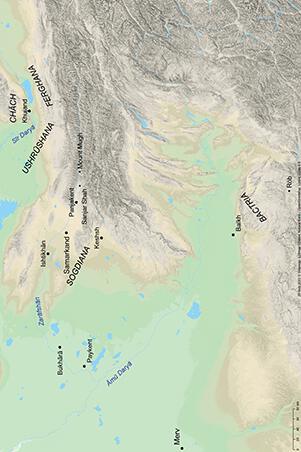

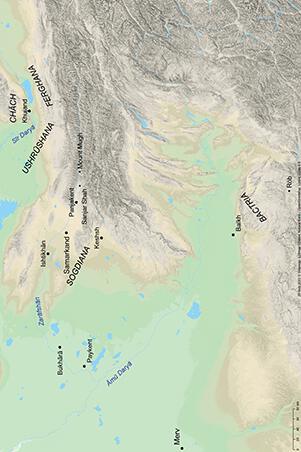

Maps

Map 1: Places of Discovery of Early Islamic Arabic Documents (Egypt and Syria-Palestine).

Map 2: Places of Discovery of Early Islamic Arabic Documents (Iran).

Map 3: Places of Discovery of Early Islamic Arabic Documents (Central Asia).

Introduction

(...) it is detestable that a man should become accustomed to speaking in something else than Arabic. Because the Arabic language is one of the symbols of Islam and Its people. Languages are among the prominent symbols by which communities are told apart.

Ibn Taymiyya, Iqti al-ir al-mustaqm.

Becoming Empire

One of the restrictions allegedly imposed on Christians from Syria and by analogy all other protected minorities by the caliph Umar I (rg. 634644), in exchange for protection and security, explicitly forbade them from engraving Arabic inscriptions on their signet seals. In this narrative, the public use of the Arabic script (not so much the practice of Arabic per se) In fact, the pacts stipulations very possibly reflect a stage in the development of Christian-Muslim relations in which ideological emphasis on distinctive cultural stuff (language, customs, dress etc.) functioned as a means to articulate and organize difference in a culturally mixed environment, in which social divides were becoming increasingly blurred.

Questions of historical veracity aside, the anecdote lays out a story of the formation of the Muslim Empire that runs parallel to the accounts of the seemingly unstoppable advances of the Muslim armies in the Byzantine Levant, Egypt, and North Africa, in Visigothic Spain and in Sasanian Iraq and Iran. The prohibition of Christians carrying Arabic signet rings presents a culturally defensive if military hegemonic minority of Arab-Muslim conquerors confronted by a multitude of cultures and peoples, striving to articulate its privileged status around a set of distinctive and monopolizable cultural markers. It also alludes to the role played by Arabic writing as a even visually distinctive public symbol in the transformation of a small minority, descended from merchants and nomads from Western Arabia, into a self-conscious ruling elite of the largest political entity of their time.