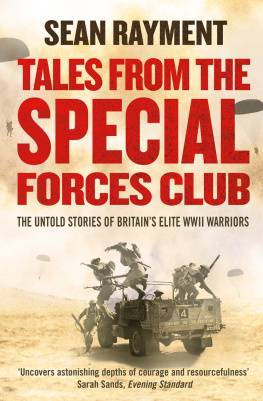

TALES FROM THE SPECIAL FORCES CLUB: AN EXCERPT

We werent bloody playing cricket

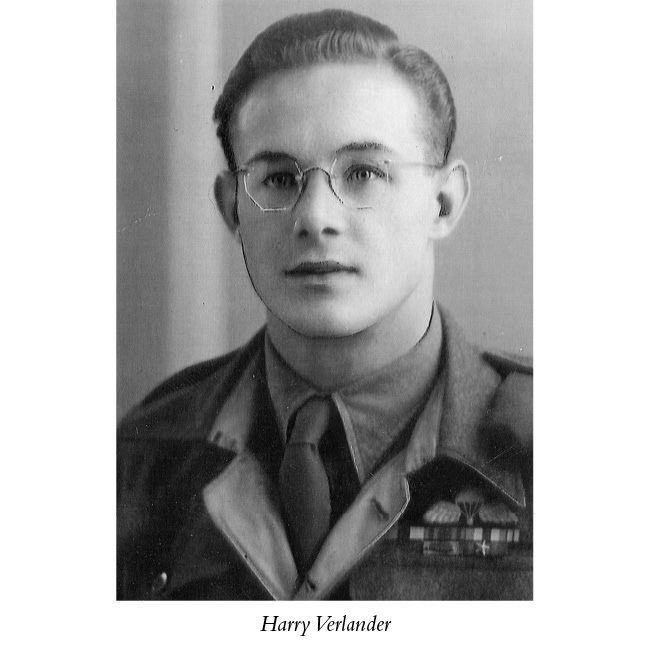

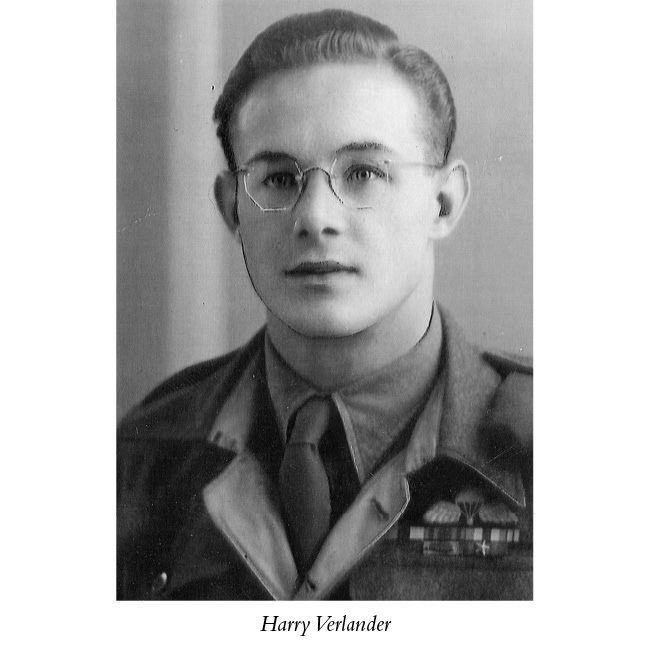

Harry Verlander in the Far East

Harry Verlander was standing in the doorway of a twin-engine Dakota as it cruised above the lush, green canopy of Burmese jungle 600 feet below. As the aircraft approached the drop zone, an RAF dispatcher tapped Harry on the back it was the signal to jump.

Leaning forward, he held his breath and threw himself into the void. Harry had jumped from an aircraft before in France the previous year, when he dropped behind the lines to help mobilise the Resistance prior to D-Day, and at the RAF base at Ringway. In all the previous jumps, however, Harry had simply dropped through a hole in the aircrafts floor good technique was not a necessity.

But jumping from a Dakota was different. As Harry exited the aircraft from a side door, he hit the slipstream with his legs apart a basic mistake and was spun like a top.

I sensed straight away that I was falling too fast. I looked up and I could see the parachute rigging lines coiled like a rope. The canopy was streaming above me completely deflated, so I began kicking and pulling and doing a lot of swearing.

Harry tugged away at the rigging lines and eventually pulled them free, allowing the canopy to form and slow his descent. But he was now way off course and, rather than drifting towards the cleared drop zone, he was heading for a steep wooded hillside.

I kept my feet and knees together, covered my face and waited for the pain. I bounced off branches and ended up tumbling through bushes about six feet high. I landed on my right leg, it took my whole weight, and there was this great surge of pain which shot up my right-hand side. I fell backwards and whiplash sent pain searing through my neck, and at that stage I passed out, briefly.

Harry regained consciousness and tried to stand but it was too painful to put any weight on his right side. His uniform had been ripped by thorns and one of the soles of his green canvas jungle boot had been torn off.

Great start, I thought. I was hundreds of miles behind enemy lines and less than five minutes into the mission. I was injured and had become separated from the rest of the team. Then just as I was getting my bearings I heard a slashing sound from the jungle ahead.

Japs! Can this get any worse, I thought to myself as I pulled out my .45, cocked it, removed the safety catch and was all but ready to fire when a young lad appeared carrying a machete. He looked at me, then the pistol, lowered the machete and smiled, and then I realised he wasnt a Jap but one of the Karen tribesmen who were helping the British push the Japs out of Burma.

The young Karen could see that Harry was unable to walk unaided, so he offered his body as a crutch. Gingerly the two men moved towards the area where Harry assumed the drop zone was located.

As the two men moved along, an older man appeared, clearly European, dressed in green jungle uniform and sporting a grey beard.

Im Lieutenant-Colonel Cromarty Tulloch, the officer in charge of group Walrus [the codename for the area in which Harry was to operate], but you can call me Pop everyone else does. Theres no rank here. Anything broken?

No, sir, I mean Pop, said Harry, still slightly bemused by the situation and unable to think straight due to the searing pain. Im just a bit beaten up and Im having a little bit of difficulty walking.

Well, well get some people to have a look at you, but you wont be able to make it to your base tonight. Youll have to rest in one of the caves and well come and get you in a few days time but dont worry, the locals are friendly and theyll look after you.

Harry was taken up to a cave in a hillside and was soon joined by the two other members of his three-man Jedburgh team, Major Sandy Boal and Captain A. Coomber.

Harry was also reunited with his pack, which contained his emergency rations, water, ammunition, grenades, some spare clothes and, most importantly, cigarettes; and the four men ate a simple meal of rice and vegetables. After the area was cleared of any sign of activity, Pop and the two uninjured members of Harrys team said their goodbyes and left, promising to return in two to three days.

As soon as I was hurt I knew that I would be left on my own somewhere safe. There was no other mode of transport, so if you couldnt walk you had to stay where you were. I wasnt at all bothered, I was armed, had my emergency rations, my cigarettes and some painkillers. I had a cigarette and settled down for the night in my makeshift bed, which consisted largely of my parachute, closed my eyes and went to sleep.

* * *

Harry Verlander was 13 years old when the war broke out and was evacuated from the East End of London until he was old enough, almost, to volunteer and join the Army. By the time he was 16 (Harry had lied about his age) he had been in the Home Guard, volunteered for military service and enlisted into the Kings Royal Rifle Corps on 19 March 1942 for the duration of the war.

But eight months later the regiment was disbanded and Harry joined the Royal Armoured Corps because it offered the best chance of seeing some action. It wasnt long, however, before Harry was to become disillusioned with life in the RAC.

Our officers in the KRRC were always around, helping us, training with us, moulding us into a team. The morale was high and we all expected to serve together. But it was very different in the RAC. The only time we saw our officers was when we were in trouble, so I began to volunteer for everything going. I volunteered to train as a glider pilot and then to join the Parachute Regiment, the Commandos and even the Palestine police, but I never heard anything back.

Then one day Fred White, who had also been in the KRRC, saw a notice on a board near to the orderly room inviting wireless operators to volunteer for special duties which may include parachute training and a knowledge of a European language would be an advantage.

Harry and Fred knew the work was obviously secret and both men decided to apply on the spot.

A few weeks later both Fred and Harry were in Oxford undergoing an interview at one of the colleges, where they signed Top Secret security forms and gave an undertaking not to repeat anything they had learnt during the day.

Through a series of lectures Harry and Fred were told of the activities of the Resistance in France and other areas of occupied Europe and of the need for highly skilled radio operators who would keep clandestine teams in contact with their home base back in Britain. By the end of the day, following a series of tests and briefings, the number of volunteers had fallen from 400 to less than 100.

Once the familiarisation visit was over, those men who were still interested were told that they would be contacted in due course and informed as to whether their services were needed. Fred received his notification before Harry, who had assumed that he had not been chosen to undergo training. Then two days later Harry was told that he too had been called forward and his delay had been caused by an administrative error.

Harry was taken up to a cave in a hillside and was soon joined by the two other members of his three-man Jedburgh team, Major Sandy Boal and Captain A. Coomber.

Harry was taken up to a cave in a hillside and was soon joined by the two other members of his three-man Jedburgh team, Major Sandy Boal and Captain A. Coomber.