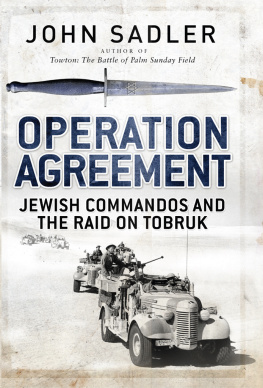

This extract is just one veteran's story. For more stories of Britian's elite warriors, buy the full ebook of Tales from the Special Forces Club by Sean Rayment

TALES FROM THE SPECIAL FORCES CLUB: AN EXCERPT

The Best Navigator in the Western Desert

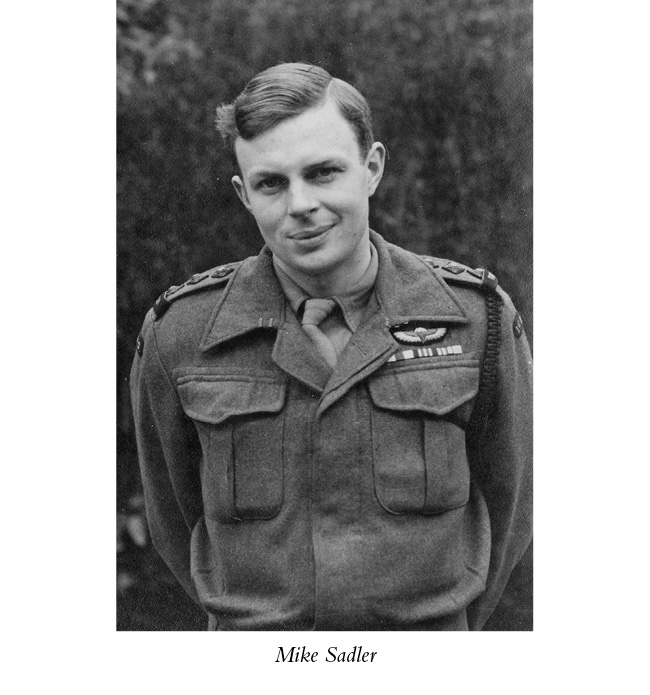

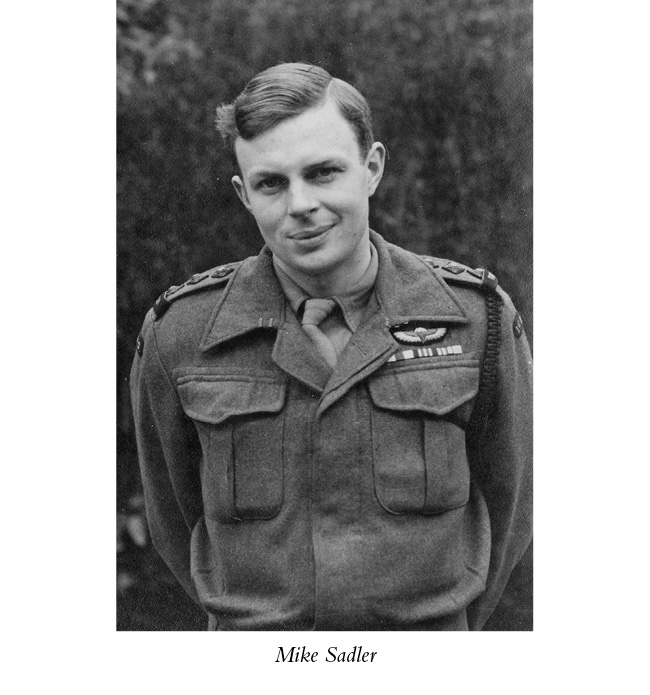

Mike Sadler with the SAS

The boy Stirling is quite mad, quite, quite mad. However, in a war there is often a place for mad people.

Field-Marshal Montgomery, describing David Stirling, the founder of the SAS

Captain Mike Sadler, MC, MM, has been famous within the world of special forces since 1942. Like Jimmy Patch, another of the veterans I spoke to, heserved in the LRDG during the North African campaign. It was Jimmy who put me in touch with him. Mike is a very nice chap and saw a great deal of action in the desert. Try and talk to him, hell have a great story to tell you.

When Mike served alongside Lieutenant-Colonel David Stirling, the founder of the SAS, and Lieutenant-Colonel Paddy Mayne, his successor, his navigating skills were legendary. He was regarded as one of the best navigators in the western desert, possessing an unerring ability to navigate by both day and night and in all weathers a skill which undoubtedly saved dozens of lives and helped to ensure the success of some of the SASs most spectacular missions during the North African campaign. Typically, he himself says he was just competent and lucky. Mike has been a longtime member of the Special Forces Club. The establishments walls are adorned with some of the operations in which Mike was personally involved. He has led a varied and fascinating life but, like many of those early members of the club, in the 1930s Mike was heading in a completely different direction until war intervened.

Today Mike lives in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, and we arranged to meet and have lunch and then, hopefully, chat about his wartime activities.

The years have been kind to Mike, who is aged 92 at the time of our meeting. Despite his failing eyesight and slightly dodgy memory, as he put it, he remains fit and active and insists we walk the mile to the restaurant for lunch.

Mike is easy-going and chats comfortably about his wartime activities. He enquires about Jimmy Patch, praising the courage and fortitude he demonstrated during the war as if it were yesterday. We didnt know each other back then, I think we must have served at different times. By the time Jimmy joined I had moved on. One story rolls out after another. He talks about David Stirling, the founder of the SAS, as if he were still alive, and he was clearly a great fan of Paddy Mayne.

When we return to Mikes flat I ask if he minds if I take notes as we talk. He looks slightly uncomfortable, and I notice his brow furrowing before he replies: I shouldnt really be speaking about any of this.

My heart begins to sink. Mike, youre 92 and you fought in a war 70 years ago. Those experiences belong to you and nobody else, I say in desperation. You wont be breaking the Official Secrets Act by telling me about what you did in North Africa.

Mike laughs. I suppose youre right.

* * *

Mikes war story began over 75 years ago when, after passing his school certificate in 1937, he left Bedales, his public school, and took more or less the next boat to Rhodesia to become a farmer.

My imagination was sparked by a friend at a dreadful prep school I attended called Oakley Hall, near Cirencester. I met this chap called Rooney and he told me all about this wonderful country Rhodesia. His stories were full of lions, elephants and adventure. I suppose it may have been a way of escaping the rigours of school life, but from a very early age I had decided that was going to be the life for me.

My family had a series of connections with people in Rhodesia and one of those was the owner of a tobacco farm. I headed off and went to work at the farm as a sort of apprentice. Tobacco was the cash crop and there were also hundreds of hectares of maize and cattle. I quickly settled into what was a really lovely life. There was a racehorse on the farm, and in the winter when there were no crops to look after we would train the horse. It was a wonderful country; it was a primitive life and it was very nice.

My family had a series of connections with people in Rhodesia and one of those was the owner of a tobacco farm. I headed off and went to work at the farm as a sort of apprentice. Tobacco was the cash crop and there were also hundreds of hectares of maize and cattle. I quickly settled into what was a really lovely life. There was a racehorse on the farm, and in the winter when there were no crops to look after we would train the horse. It was a wonderful country; it was a primitive life and it was very nice.

His idyllic but austere lifestyle in southern Africa came to an end two years later in September 1939, when Britain declared war against Germany. Mike, like millions of other young men across Britains vast empire, volunteered for active service.

I joined the Rhodesian Artillery. The men within the unit were all very keen but our equipment was very basic. We had 3.7-inch Howitzers, screw guns from Kiplings day, all very antiquated but useful and still functional.

During that period I learnt how to fire guns using aiming marks and also learnt the appropriate size of charge. Pretty soon after that we drove up to Kenya, chased the Italians up through Somaliland and into Southern Abyssinia, then moved up to Suez, where we joined up with the 8th Army. The Rhodesian Regiment was affiliated to the 60th Rifles, so the connections were already strong.

During the early part of 1941 Mikes battery, which had converted to an anti-tank unit, were based in the desert west of Mersa Matruh, a small town on the Egyptian coast west of Alexandria, preparing for the great German advance eastwards across the desert. The days were long, cold and mostly uneventful. Engagements with the enemy were rare events. The monotony of digging endless tank traps and bunkers was only broken by long and equally uneventful patrols out as far west as the escarpment at Tobruk in Libya.

But those dull days suddenly changed during a period of leave in Cairo. Mike and a few pals from his unit were enjoying an early evening drink at the Rhodesian Club when they started chatting to members of a unit whose name the Long Range Desert Group was unknown to them.

Mike was attracted by the stories of their exploits and the freedom they enjoyed to operate behind enemy lines with little interference from senior officers.

My recollection is that we all got on very well. Their unit needed an anti-tank gunner and they said, Why dont you come and join us? I was young, keen and fit; I was delighted to be asked. The work they were doing sounded infinitely more exciting than digging tank traps, so I joined. It was probably a bit more complicated than that, and Im sure there was a lot of staff work that needed to be done to have me transferred across, but thats how I remember it.

I spent two weeks at Abbassia Barracks in Cairo, and then joined up with an LRDG re-supply column, consisting of mostly 3-tonners and a couple of Fords, and their job was to keep the LRDG patrols supplied with food, ammunition and anything they needed.

It was during Mikes long journey down to the headquarters at Kufra that he began to take an interest in desert navigation.

As the convoy headed south, Mike was struck by the beauty and majesty of the desert and was amazed at how quickly the hostile environment could change. Vehicles could be speeding along flat, road-like desert surfaces at one moment, only for the terrain to change in a matter of seconds to a rock-strewn wasteland capable of tearing tyres to shreds.

My family had a series of connections with people in Rhodesia and one of those was the owner of a tobacco farm. I headed off and went to work at the farm as a sort of apprentice. Tobacco was the cash crop and there were also hundreds of hectares of maize and cattle. I quickly settled into what was a really lovely life. There was a racehorse on the farm, and in the winter when there were no crops to look after we would train the horse. It was a wonderful country; it was a primitive life and it was very nice.

My family had a series of connections with people in Rhodesia and one of those was the owner of a tobacco farm. I headed off and went to work at the farm as a sort of apprentice. Tobacco was the cash crop and there were also hundreds of hectares of maize and cattle. I quickly settled into what was a really lovely life. There was a racehorse on the farm, and in the winter when there were no crops to look after we would train the horse. It was a wonderful country; it was a primitive life and it was very nice.