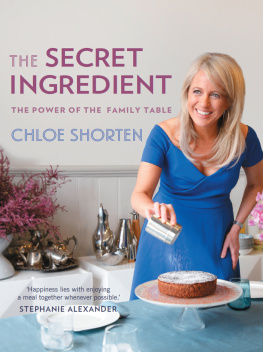

Chloe Shorten is a communications specialist, Queensland girl, mother of three and an advocate for improving the lives of women, children and people with disabilities. She lives in Melbourne and is married to Bill.

For our dear children

Rupert, Georgette and Clementine

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 715 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

www.mup.com.au

First published 2017

Text Chloe Shorten, 2017

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2017

The poem Children learn what they live on p. 147 1972 by Dorothy Law Nolte.

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Cover design by Clare OLoughlin

Typeset in 12/16.5pt Bembo by Cannon Typesetting

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Shorten, Chloe, author.

Take heart: a story for modern stepfamilies/Chloe Shorten.

9780522871326 (paperback)

9780522871333 (ebook)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

FamiliesAustralia.

StepfamiliesAustralia.

Domestic relationsAustralia.

Domestic relationsAustralia.

Contents

The book I wanted to read

W HEN I DECIDED to remarry and bring a stepfather into my childrens lives, I needed to get it right. I owed that to my kids.

I consulted experts for high-quality advice. I asked people I knew how they did it. There was a great bookstore in Brisbane opposite my office, and I scoured its shelves for stories of successful outcomes for stepfamilies and particularly for the children involved. There are so many stepfamilies in history, with empires and monarchies built on remarriages! Completely head over heels and about to marry again, I wanted to show myself, my family and even my former husband it would all be okay. But the books I found were either instructive how to ones that didnt include success stories or had titles along the lines of Help! Yikes! We Are a Stepfamily or Im No Stepmonster that frightened me off. Later on, I would spend an entire day in a massive Barnes & Noble store in New Yorkarguably a mecca for self-help, how-to and relationship advice books. But, again, what I really wanted wasnt there. Searching online bookstores wasnt very uplifting either. Meanwhile, it struck me that the media portrayed stepfamily situations unrealistically, with evil step-parents permeating TV shows and magazine articles.

I wanted to alleviate my anxiety, to empower myself with validating tales of the diverse and wonderful families I firmly believed ours could be. I knew we werent alone, because in my quest I read all the research I could find. In Australias population of 24 million people, there are around 5.7 million families with children and 2.8 million of these include kids under eighteen. A whopping 43 per cent of the kids under thirteen have experienced living outside the typical nuclear-family structure (Baxter, 2016a).

These are children in stepfamilies, and in lone-parent families. Many of these are shared-care families, where the children might live primarily with one parent but spend time with their other parent; or may be one of the small, but growing, number of families where children spend roughly equal time with each parent after a divorce. There are same-sex-couple families, and children living with grandparents or other relatives. So, modern Australian families are a tremendous mix. As the great chronicler of family life in this country, the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS), found in October 2016, more than two in five Australian children experience living in families who dont fit the stereotype of Mum, Dad and a brother or sister.

Research shows the majority of kids do well in these environments, and for some, the change in their family life is of great benefit. While I think its important to acknowledge the value of growing up in stable nuclear families, it is also crucial to be positive towards, and supportive of, those who are part of what academic lingo now calls complex families. While I think that term is useful for research purposes, I just call these families the new normal.

I needed to see stepfamily life in all its permutations and not through the lens of how a nuclear family evolves. I longed for long-term studies that showed how stepfamilies who do well did it; I wanted to soak up joyful, moving and funny stories I could use as a model, and that would reassure the children and me, and enlighten and encourage my new husband, Bill Shorten, who was then a member of the Australian parliament. I wanted stories showing that with effort and the right kind of environment, kids in these sorts of very modern families actually thrive.

It was in the absence of instructive tales about, and models of, healthy stepfamilies that I turned to the research. The complexity of some family structures, the number of households involved, and the reluctance of some to identify as being in stepfamilies or to disclose any details means that real data is hard to get. The 2013 Family Characteristics report taken from the Australian census clearly warns its stepfamily statistics have 2550 per cent unreliability for these reasons. So, the bulk of the long-term literature on stepfamilies is largely authored overseas, the accounts are often based on deficits and pathologies, and the figures are easy to misinterpret. As a career researcher and a big believer in evidence-based decision-making, I was gobsmacked. How can we, as a society, possibly be making good decisions, and creating good policies, services and support systems, for a huge and growing number of Australian families?

Relief came when I discovered new research that academics, clinicians and practitioners from the US, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the UK have painstakingly undertaken. I have now read hundreds of academic papers, articles, books, speeches and editorials, and spoken to experts everywhere. Happily, in all this I found the most extensive examination of Australian stepfamilies ever undertaken. Growing Up In Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children looks at 8000 children from all states and territories whose lives researchers have focused on for more than a decade.

Also, demographer and senior research fellow Dr Jennifer Baxters work for the AIFS is based on the longest-term analysis of the largest number of Australian families ever undertaken. Her report Diversity, Complexity and Change in Childrens Households was released just as I started writing this book, with the AIFS saying, The [Baxter] study showed that a significant number of children live in more complex households, with the potential for this to impact both positively and negatively.

All this has convinced me even more that not just interested parents like me but the whole community need to talk more about valuing families in all their wonderful complexity. As society changes, so do families, and we need to agree that different sizes and types of families are okay (and inevitable). We need broad understanding that the health of these microsystems is vital to our national wellbeing. That its what we do within those families, how we learn from the lessons of the past and the researchers toil that matters. That if we understand the imperative of consistent care, and a broad support network for children and parents, a warm, strong parenting method, and a community that doesnt judge and a system that supports them, then the kids will be all right.

Next page

![Chloe Caldwell [Chloe Caldwell] - Women](/uploads/posts/book/114454/thumbs/chloe-caldwell-chloe-caldwell-women.jpg)