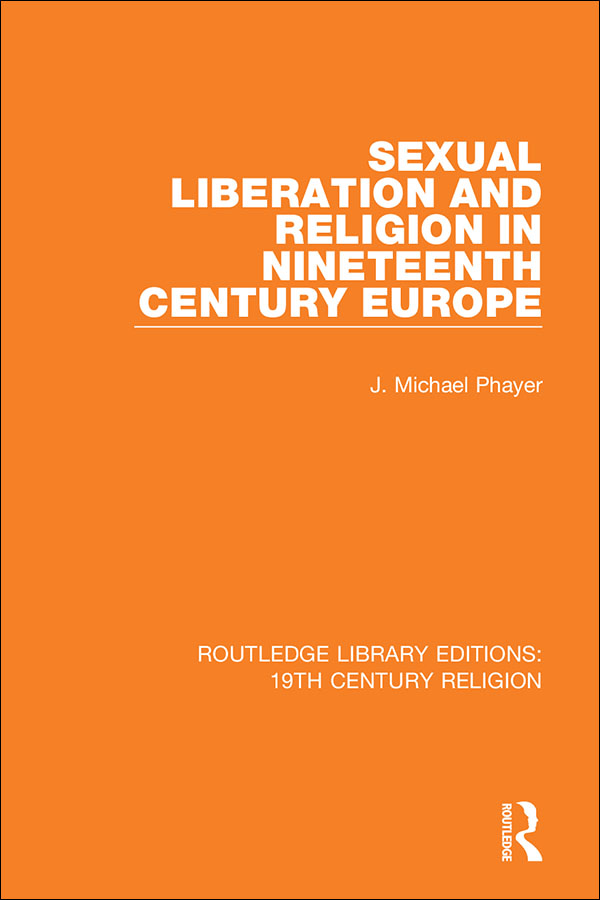

First published in 1977 by Croom Helm Ltd

This edition first published in 2018

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1977 J. Michael Phayer

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-138-06800-1 (Set)

ISBN: 978-1-315-10089-0 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-08460-5 (Volume 17) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-11169-8 (Volume 17) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

SEXUAL LIBERATION AND RELIGION IN NINETEENTH CENTURY EUROPE

SEXUAL LIBERATION AND RELIGION IN NINETEENTH CENTURY EUROPE

J. MICHAEL PHAYER

1977 J. Michael Phayer

Croom Helm Ltd, 2-10 St Johns Road, London SW11

ISBN 0-85664-230-4

First Published in the United States 1977

by Rowman and Littlefield, Totowa, N.J.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Date

Phayer, J. Michael.

Sexual liberation and religion in nineteenth century Europe.

Bibliography: p. 165

Includes index.

1. Sex and religion History. 2. Germany Christianity. 3. France Christianity.

I. Title

HQ63. P47 261.8341 76-30351

ISBN O-87471-947-X

Printed in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, Guildford, Surrey

Popular belief and behaviour changed with the advent of modernisation. How and why they changed is what concerns us in this book. The process treats the historian to a fascinating chapter in social history; how did people manage to steer straight ahead in matters of religion while veering off sharply in sexual conduct? Because we commonly associate sexual liberation with modern secularity and religious piety with tradition and the past, they seem to run off in opposite directions. But the experiences of European people in the first half of the nineteenth century do not bear this out. Most Germans and Frenchmen, especially people in the lower class, became more sexually permissive while remaining religious.

Perhaps it has been the sensitivity of secular humanists that has kept us from plunging into an analysis of this relationship. Doing so sometimes casts an unflattering light on religion and, at other times, displays it in full retreat. On the other hand, perhaps it is simply the lack of an informed acquaintance with Baroque religious tradition that has protected the nakedness of the relationship from the historians eye. For whatever reason, the result has been unfortunate in several ways.

In the first place, the discrepancy between religious tradition together with its moral code of behaviour and modern sexual freedom poses a dilemma for Western society. Modernisation has introduced principles of behaviour that often contradict those which religion has sought to maintain. While relishing personal sexual freedom modern people hesitate to jettison their religious tradition. Meanwhile, many churches have fought a rear-guard action to adjust the Christian code to recent circumstances, such as abortion and divorce, and contemporary situations (pre-marital and extra-marital sexuality and homo-sexuality). Others, alternately, steadfastly hold tight to traditional moral guidlines and jeopardise the credal belief of their members.

It is by no means clear what the resolution of this dilemma will be. Much hangs in the balance. If the Western tradition of moral monotheism disappears, what values or value systems will society adopt? Besides fragmenting and pluralising us, how will they change us? At the very least we may be assured of a deep character transformation in Western society. Alternately, should the traditional code which has been put in question reaffirm itself, hard and difficult decisions loom on the horizon, given the new pattern of sexual behaviour.

Second, entirely practical considerations compel us to deal with the origin of the dilemma. Ever since historians have interested themselves in the history of sexual behaviour, gnawing doubts about the subject have beset them. Statistics have convinced some of the fact of significant sexual change. But while we have groped to find the causes of this new conduct, doubters have asked if it is at all likely that any massive change in an area of such fundamental human behaviour as sexuality could occur. And to such Cartesian minds the glimpses into the causes of sexual change on the part of those who affirm a sexual revolution seem all too fleeting.

This study demonstrates that a change in mentality cut common people adrift from traditional sexual controls and allowed them greater sexual freedom and indulgence. The process occurred in such a way that, incredible as it may sound, the proletariat never considered whether their newly found sexual liberation might be in conflict with the moral teachings of their Church.

The circumstances that furnish the historical evidences of this proposition vary. Determining just which Germans were affected by sexual change and which were not poses no problem. Early nineteenth-century sources allow us to follow this development with amazing precision. By comparing tax records from state archives with parish records from church archives it may be asserted that differences in sexual behaviour constitute one of the earliest earmarks of class society. At the same time, the continuance of traditional religious practices and customs permits us to bring into focus a more complete and composite picture of the early nineteenth-century Central European proletariat than we have hitherto known.

Because most of the documents in question derive from Catholic Germany, it is difficult to say to what extent the experience of Protestant Germans ran parallel. There are suggestions and evidence indicating both a similarity with Catholic Germany and a different relationship between belief and behaviour.