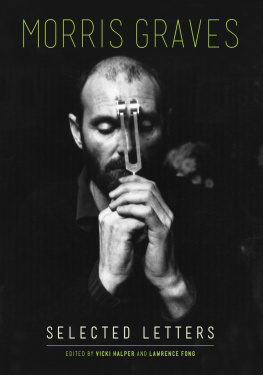

MORRIS GRAVES

SELECTED LETTERS

Edited by Vicki Halper and Lawrence Fong

A McLellan Book

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS SEATTLE & LONDON

This book is published with the assistance of a grant from the McLellan Endowed Series Fund, established through the generosity of Martha McCleary McLellan and Mary McLellan Williams.

2013 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in China

Designed by Annabelle Gould

Composed in InDesign, typefaces designed by Chris Burke (Celeste), Hannes von Dhren (Brandon Grotesque) and Morgan Knutson (Mensch)

18 17 16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

University of Washington Press

PO Box 50096, Seattle, WA 98145, USA

www.washington.edu/uwpress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Graves, Morris, 19102001.

[Correspondence. Selections]

Morris Graves : selected letters / edited by Vicki Halper and Lawrence Fong. First [edition].

pages cm

A Samuel and Althea Stroum book.

ISBN 9780295992143 (hardback)

1. Graves, Morris, 1910-2001Correspondence. 2. PaintersUnited StatesCorrespondence. I. Halper, Vicki, editor of compilation. II. Fong, Lawrence M., editor of compilation. III. Title.

ND237.G615A3 2012 759.13dc23

[B]2012026655

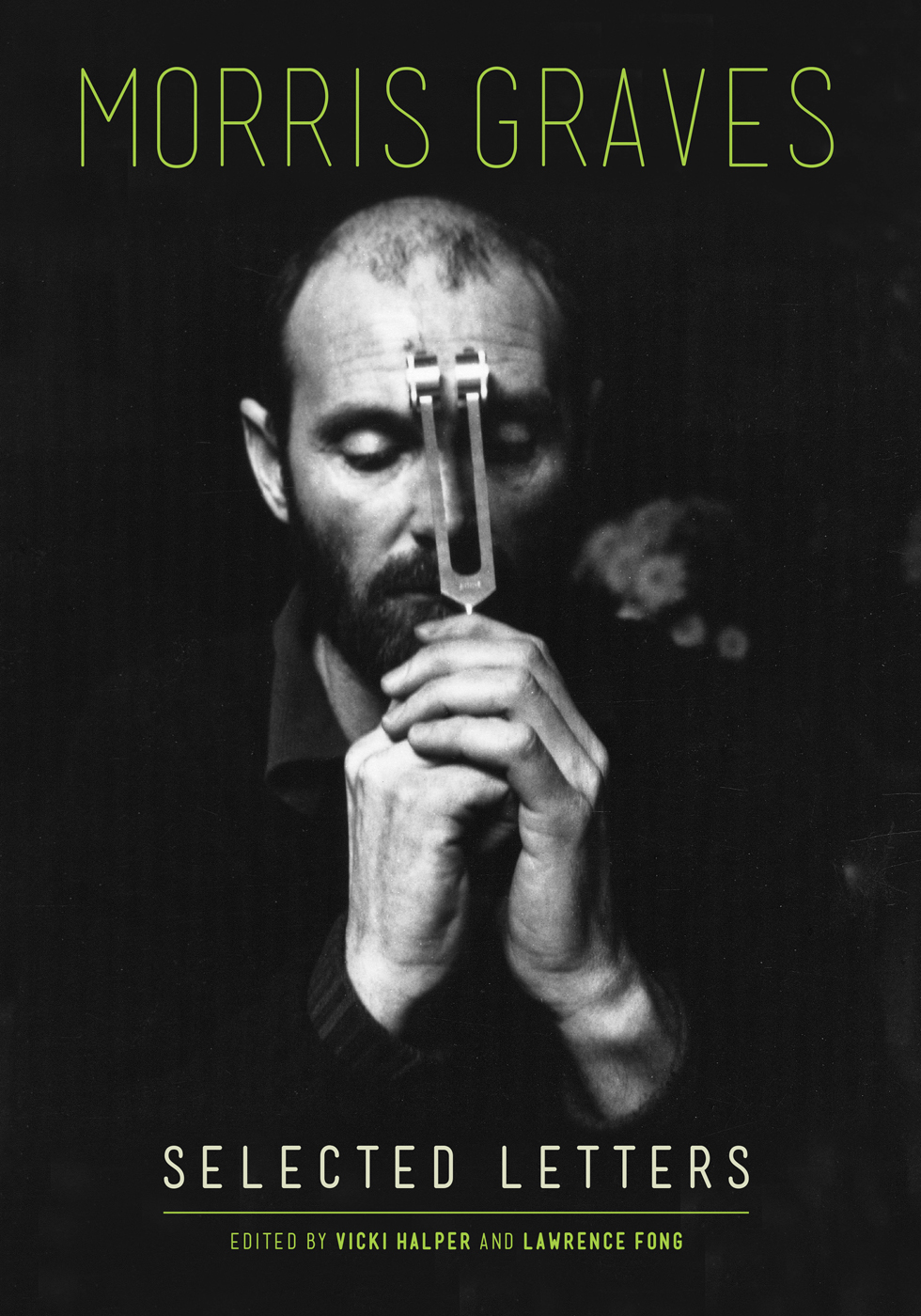

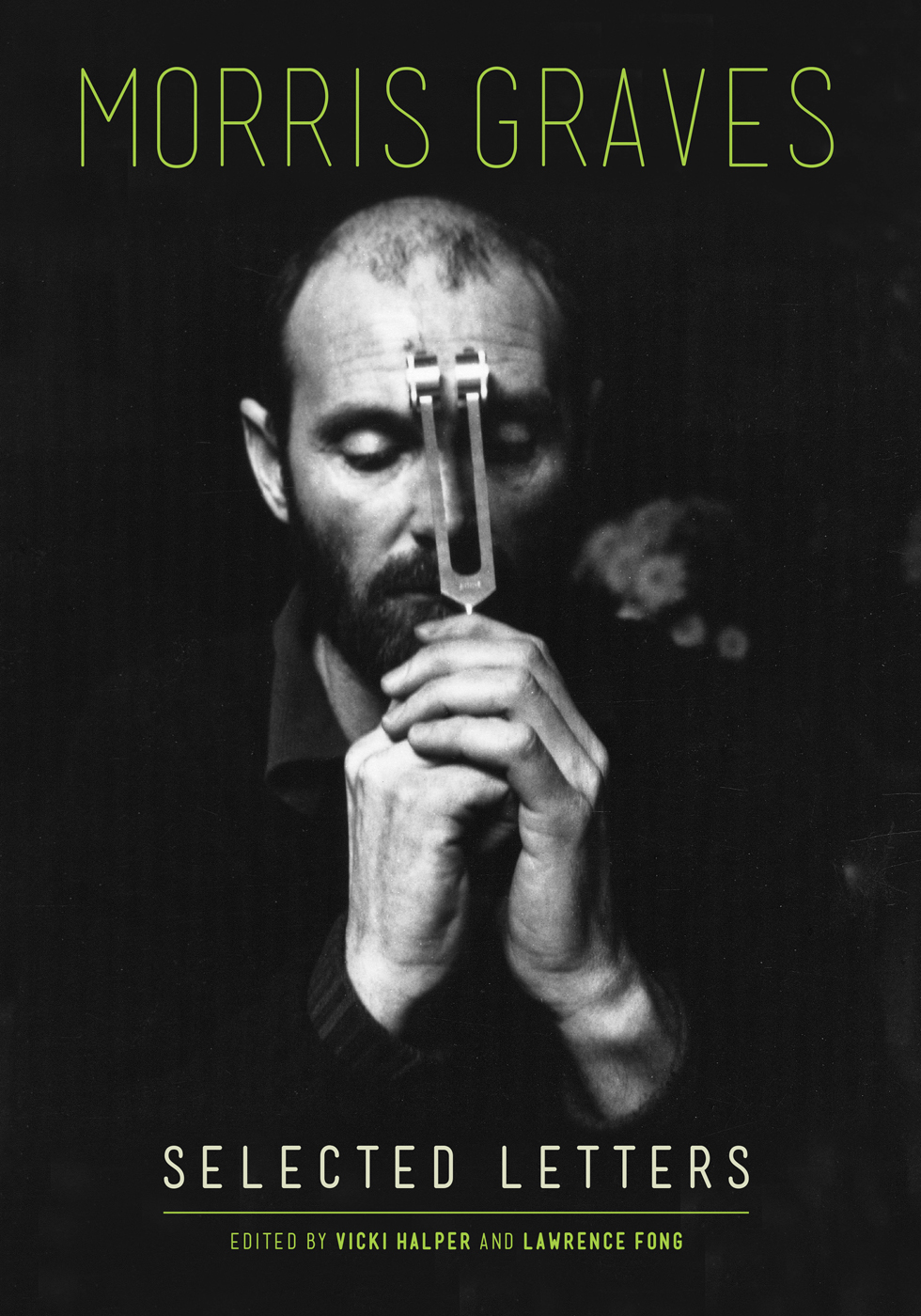

Cover: Dorothy Norman, Morris Graves with Tuning Fork, ca. 1955. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Clinton Walker Fund purchase. 2000 Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona Board of Regents. Photo by Dorothy Norman

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

CONTENTS

Morris Graves, Flowers, 1957. Watercolor and tempera on paper, 13 9 in.

Collection of Margaret Norman. Photo by Johnna Arnold

INTRODUCTION VICKI HALPER

Despite his recurring dismay over the demands of letter writing, the painter Morris Graves (19102001) was a committed, sometimes obsessive, correspondent. His need to describe, justify, expound, and verbally delight faltered only in his old age. He wrote multiple drafts of even the simplest letters, not only to correct his poor spelling but also to better mold his thoughts. Given his large script, his letters were often over ten pages long. Graves regularly added postscripts to amend or emphasize what he had just penned. He saved his drafts, and many correspondents kept his letters. Perhaps family and friends predicted future greatness, as he did himself, or treasured his insightful, heartfelt prose as an additional art form practiced by the artist.

In the first letter in this book, Gravess father remarks on his sons literary skills: Your description of the canvas you are now working on was much enjoyed by me. My mind leans toward writing and I think yours does too. I am judging now by your word picture of your newest attempt. To his sons accomplishments as a painter, architect, interior designer, and landscape designer, we can add his skill as a writer with a similar intensity, and often with a similar finesse.

Morris Graves was a key figure in the Northwest School, a group of Seattle-area artists who shared an interest in Asian philosophy and aesthetics starting in the 1930s. In the early 1940s the Museum of Modern Art exhibited and purchased Gravess work. Other significant purchases were made by the Metropolitan Museum, the Phillips Collection, and the Seattle Art Museum. The Willard Gallery in New York represented Graves and Mark Tobey, the other noted artist in the group, and regularly exhibited their paintings in one-person shows. In 1953, after the close associations between the artists had virtually ended, a Life magazine article titled Mystic Painters of the Northwest codified the group in the popular imagination. Two retrospective exhibition of Gravess work traveled nationwide starting in 1956 and 1983.

Graves was a lifelong aesthete. His interest in objects, architecture, interior design, and painting was evident by his teens. His theatrical persona was likewise cleardramatic moods punctuated his life, and examples of despair, anger, and elation are repeatedly recorded in his correspondence. Although his emotions could be operatic, they were not false, which may be why his dearest friends were accommodating and lasting. While some blamed Graves for grandiosity, particularly as evident in the homes he maintained, others reveled in the orderly beauty of the spaces he designed and in the delight of his loyal, playful, and heartfelt spirit.

The earliest letters in the book (in ).

The letters of the 1940s, mainly preserved in the Willard Gallery archives, are central to understanding Gravess worldview and the meaning of his art. The World War II years were ones of both fame and torment for Graves, who refused to serve when inducted into the army in 1942. Held in military camps for about a year, Graves had ample time for rumination and writing. He had a romanticized view of Japanese culture, and a Hindu belief in the illusory nature of the material world. This belief did not, however, lead to a renunciation of the comforts that were necessary to his productivity.

Gravess attempt to create the perfect home, the main characteristics of which would be spacious order and seclusion, started before his internment and continued for decades afterward. When the homes, or the surroundings, invariably turned out to be less than his ideal, Graves moved, seemingly at the point at which a project had reached its conclusion. The reason for flight might be ambient noise, frustration with builders, overwhelming personal entanglements, or homesickness for the Pacific Northwest. The huge financial burdens of these projects consumed Graves and strained his relationships with his dealer and patrons. Visitors testify, however, to the immense beauty of the places Graves built, with their geometric but abundant gardens, perfectly scaled rooms, and exactingly selected and placed furnishings.

, Nesting, examines Gravess residences. They are mentioned by name throughout the book and are therefore summarized here:

1940ca. 1947 | The Rock, Fidalgo Island, near Anacortes, Washington |

1947ca. 1954 | Careladen, Woodway neighborhood of Edmonds, Washington |

195864 | Woodtown Manor, near Dublin, Ireland |

1964death | The Lake, Loleta, California |

The 1950s, when Graves spent much of his time abroad, are filled with letters. When Graves returned to the States and built his final home in the Northern California redwoods, the volume of correspondence with close friends began to ebb. He was consumed with building, then entranced with the youth culture of the 1970s. Long-distance telephone service was no longer exotic. He made cyclical recommitments to solitude. Correspondents died. Robert Yarber, Gravess companion and caretaker for the last twenty-eight years of his life, lived in an adjacent house. There was no need for letters between them.

Next page