Chapter 3

Library

F itting with the nature of the room, the ambience in the library is high country, decorated with casual comfort in mind but with a slightly more formal feel provided by the furniture produced in the early years of British settlement in eastern Canada. The more formal mood is, however, immediately softened with the floor-to-ceiling book shelves flanking a fireplace at the far end. Interspersing the books with strategically placed folk art also lightens the look and adds depth to the room.

The oval painting above the fireplace depicts a pivotal point in Canadian history recording the death of General Wolfe at Quebec, while also serving an important secondary function of hiding the television behind a hinged, easy-to-swing panel.

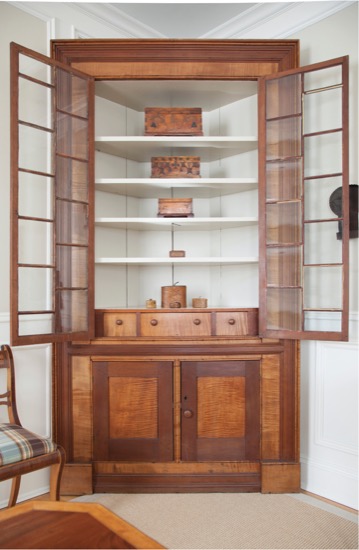

Tiger Maple Corner Cupboard

Rooms with high ceilings can be difficult to decorate, breaking it up with a single large piece can be effective, whether it is a painting, furniture, or an architectural element.

Anchoring the library to the left of the entry is a tall glazed corner cupboard in figured maple and cherry from the Eastern Townships in Quebec; in the right corner is an Ira Twiss long-case clock in original grained surface, also from Quebec.

The simplicity of the corner cupboard is deceptive, as the clever use of the contrasting woods gives it an understated elegance that blends perfectly with the formal Maritime furniture elsewhere in the room. The use of cherry for the surround moulding and door frames complements the rich tone of the tiger maple primary wood. The surround moulding also frames the cupboard within the space, minimizing the scale somewhat. The alternating ladder arrangement of the mullions in the upper doors is unusual, as are the three drawers in tiger maple discreetly tucked away. The cupboard interior, with its original shelves, is overpainted in a matte off-white to soften the presence and provide an appropriate backdrop for the objects within.

Eastern Townships, Quebec, 1825-1840, excellent original condition including hardware and knobs.

Ex collection: George and Louise Richardson, Toronto.

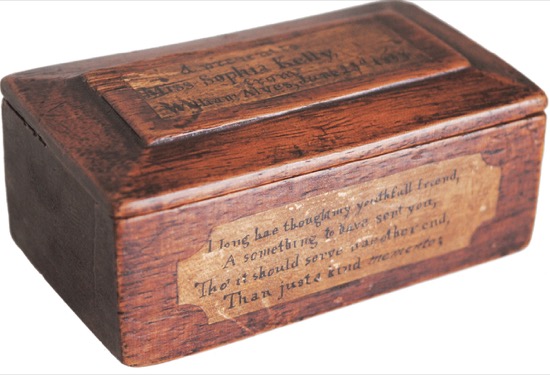

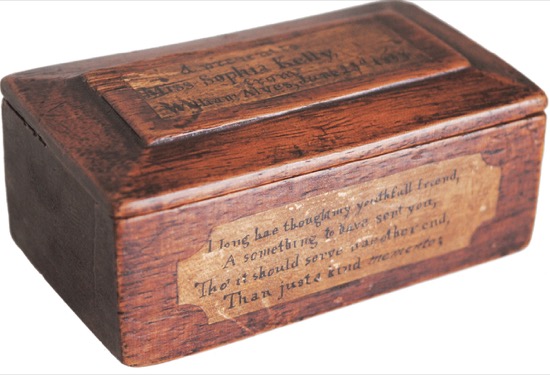

1837 Rebellion Box

It is easy to dismiss this tiny box with its finely inked script, but its place in Canadas history revolves around a story of passion, politics, alleged treason, and eventual death for some involved.

Rebellion boxes, like this one by William Alves, are also known as prisoner boxes or, morbidly, coffin boxes due to their shape and the perceived fate of their makers, all prisoners in the Toronto Jail awaiting trial for their role in the political rebellion of 1837 against the controlling power of the British in Upper Canada.

In early December 1837 a group of rebels led by William Lyon Mackenzie stormed down Torontos Yonge Street on a mission to overthrow the government. Mackenzie had formidable credentials: newspaper publisher, former Member of Parliament, former mayor of Toronto, and a vocal political advocate for constitutional change.

Mackenzie and his men were forced to retreat, and two days later the authorities launched a devastating raid of Mackenzies headquarters at Montgomerys Tavern. Mackenzie had chosen to launch the rebellion at that time because of a reduced local military presence due to local troops being deployed to Lower Canada to quell a similar uprising in Quebec led by Louis-Joseph Papineau.

William Alves was an idealistic 21-year-old employee at Montgomerys Tavern who was an ardent follower of Mackenzie and his cause; he was one of only 12 reformers sent to England for trial at the Old Bailey Courthouse in London. Alves was pardoned on condition that he not return to Canada and eventually settled in Ohio. Two of the organizers of the Rebellion were not so fortunate: Samuel Lount and Peter Matthews were hanged in Toronto in 1838. With a bounty on his head, William Lyon Mackenzie escaped prosecution by fleeing with other rebels to the United States; amnesty was decreed in 1849 and he returned home, eventually resuming a political career in Toronto.

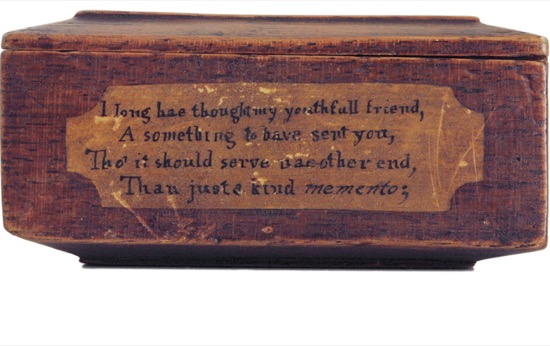

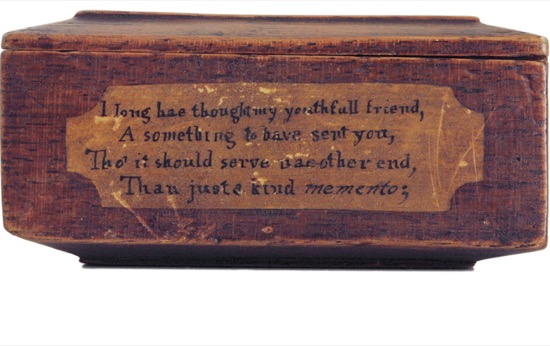

According to From Hands Now, Striving to be Free (York Pioneer Society, 2009) this is one of two boxes completed by William Alves, the first one dated April 1838; the rebellion box in this collection was created after the young Alves had spent six months in jail, just prior to his trial in London, England. The top is inscribed A present to Miss Sophia Kelly, from William Alves, June 23, 1838 while sides and bottom are inscribed with a poem inspired by Robert Burns. Was William a tentative suitor to Miss Kelly or was he just a friend?

Rebellion boxes are small (this one measuring 3.5 in length) and were made not only as a means to pass the time but also as a way for the rebels to express their feelings towards their cause and their loved ones. This box is typical, carved from a single piece of scrap wood with no joinery, and a sliding lid with a bevelled perimeter around a raised rectangular panel; the box is stained a reddish brown with lighter- colour, linen-fold panels on each side to accommodate the black script.

An interesting footnote to the story is that among the government forces in the attack on Montgomerys Tavern was 22-year-old John A. Macdonald, destined to become Canadas first prime minister in 1867. A few decades later the rebellion leader Mackenzies grandson, William Lyon Mackenzie King, would take his first steps toward becoming the longest-serving prime minister of Canada.

I long hae thought my youthfull friend,

A something to have sent you,

Tho it should serve nae other end,

Than just a kind mementoe;

Oft clinging to the mossy grate, [perhaps the jail house door]

To catch a glimpse of heavens pure light,

Uncertain as to future fate,

Yet hope in God to set all right;

The end of the poem is inscribed on the bottom of the box and unfortunately has worn away with time.

Carved Brush

Every collection has a what is it? and this collection is no exception. Proudly displayed standing on a shelf in the tiger maple corner cupboard is an elongated brush, undoubtedly very old and made with care and skill, featuring carved motifs and a bristled hide neatly affixed with pegs to the wooden haft. It was likely made for a very specific purpose; however, research to date has proved fruitless in finding another example or information regarding its application.

Found in Quebec and carved in birch, the brush likely dates to the 18 th century, judging from the carving style, shrinkage of the hide, patina of the wood, and the use of wooden pegs in lieu of iron brads. The style and nature of the carving detail point to a Native origin: the tree motif on the back, the carved zigzag pattern in the centre, and especially the human head forming part of the pommel. The shape of the head and its facial details, especially the light moustache and beard, suggest an East Coast or subarctic tribe. Although facial hair was not the norm for indigenous people, early exposure to Europeans inevitably introduced different genetic characteristics. For example, several 19 th century portraits in the collection of the Nova Scotia Museum show Mikmaq men with moustaches, beards, and even muttonchop sideburns.