Introduction

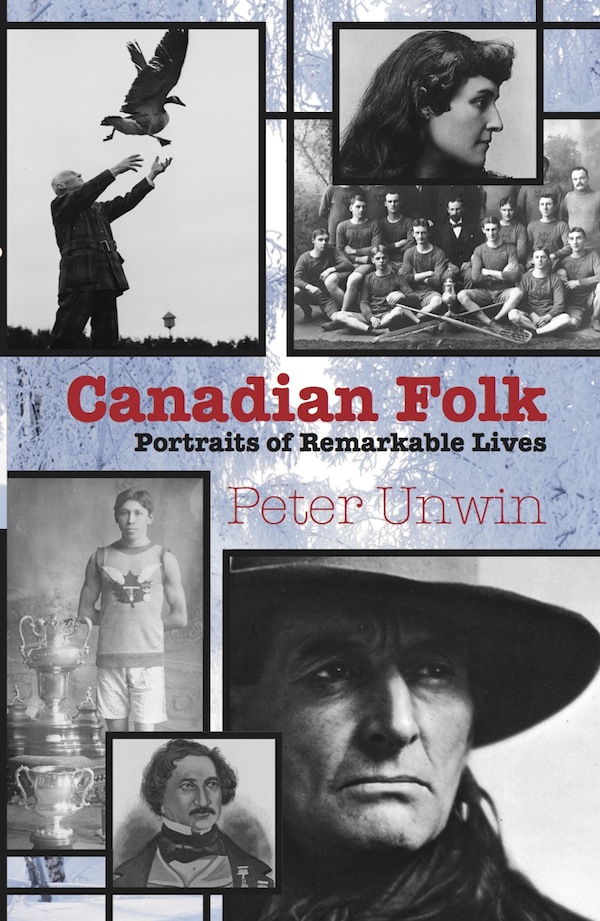

I n writing and researching Canadian Folk , I was perhaps fortunate to arrive at no conclusive insights into Canada or Canadians. What I repeatedly encountered was the notion that to be Canadian, or to attempt to qualify as one, involved travelling great distances by canoe, by train, or boat, on foot, by dogsled, by snowshoe, or any combination of the above. Frequently this travel was undertaken during a blinding snowstorm or in a sinking ship, in which the captain was drunk and probably the ship was on fire.

More often than not the people who inhabit Canadian Folk were marked by a noticeable inability to sit still. They were perpetually northbound or south; they were inveterate walkers, or world-class runners, millionaires in ill-advised Citron half tracks. The restless characters who spanned those miles, and who fill the pages of this book, were fuelled by the ambitions, the doubts, and the certainties of their times, a certainty that now seems unfathomable to us and frequently maddening.

More than a few started out fascinated by the forest and what they hoped was the redemptive power of the wilderness and a Native way of life. Some were Native themselves, or wanted to be, or tried to be, and did not fit easily into the book of history. Some were celebrated or reviled around the world, some were clubbed to death on remote islands, some were hateful, others sublime in their decency and manners.

Many of the people in this book left extensive records of their passing in the form of poems, letters, books, or paintings. Some of them painted on ancient rock using a form of paint that defies science. All of them travelled through the vast kingdoms of the Native gods of North America, whose names were often unpronounceable and unknown to them. A few had the responsibility of watching entire ways of life vanish before their eyes.

Today we know them by their vitality of their existence, or sometimes by the damage they left behind. More often, and increasingly, we dont know them at all.

1

A Misserable Barren Place

T he year of his birth is not known. It is usually approximated around 1640, although recent evidence uncovered in New England may force the date forward. The year of his death is not known, either. It would seem he died under mysterious and extremely grim circumstances on Marble Island, twenty-five miles off Rankin Inlet, in 1720, or 1721. Even what he looked like is unknown, there being no portrait painted, or none that has passed into history. What evidence there is suggests a man who left behind a legacy of resentfulness, jealousy, almost unbelievable hard work, and suffering; a grim, humourless character who, for half a century, dominated the lower half of Hudson Bay.

What is known of James Knight is that in 1676 he entered the service of the Hudsons Bay Company already a mature man and a shipwright by trade. In this same year or shortly after, following an ocean voyage that lasted eighty days, he entered, for the first time, the ferocious Western Sea of Hudsons Bay. His assignment was to build or rebuild the Companys forts and factories at the Bottom of the Baye. Of this first encounter he would write tellingly forty years later: It has been My Misfortune Always to have Nothing but Fatigue and Trouble in this Countree, for when I first came into it wee had Nothing but a little place not fitt to keep Hoggs in.

For some reason no amount of Fatigue and Trouble could keep James Knight out of this Countree. By 1682 he was outfitted for a return voyage, this time as deputy governor. It is typical of the mans abrasive relationship with almost everyone that on the day the expedition was to sail, the London-based Committee of the Hudsons Bay Company, concerned that Knight would engage in private trade, refused him the right to board the ships. Somehow the conflict was resolved and he sailed the same day.

As second-in-command, Knight served under Governor John Nixon, a tetchy, sanctimonious disappointment who excused his own fondness for liquor on the grounds that Water doth not agree with me. His own men were said to be appalled by his savage treatment of the Natives. Perhaps it is telling that this is one of the very few men with whom James Knight did not clash.

These relations changed when Nixon was replaced as governor by Henry Sergeant. Hand-picked by the Duke of York, Sergeant had pertaining to him a parcel of women: his wife, her friend, and a maidservant, the first white women to winter in Hudsons Bay. Almost immediately the new governor directed charges against Knight, likely to the effect that Knight was packing out skins for private sale. Returning to England in 1685, Knight dodged these charges by proposing a scheme to reduce the costs of maintaining outposts at the Bottom of the Bay. He also produced testimonials to his character which, in his own mind, exonerated him. In the minds of the Committee, however, James Knight was not to be trusted and there followed a seven-year absence from Company employment. During this time, the reputation of Henry Sergeant fell dramatically when he surrendered Albany Fort to the French without a fight. It is said his wife fainted at the first shot and the rest of the English garrison retreated into a cellar and cowered there. For this ill Conduct, perfidiousness & Cowardize, the Company presented the disgraced governor with a bill for 20,000. Despite a lengthy court battle, they never collected.

In 1692, James Knight was back in favour and granted the title of Governor & Commander in Cheif of all and every of Our Forts Factorys Lands and Territory with the dependencys contained and lying in ye bottome of the Bay commonly called Hudsons Streights in America. In 1693, he led a powerful force into Hudsons Bay and retook Albany Fort from the French. After a furious first fusillade, Knight discovered the fort empty but for a prisoner clapped in irons. The man, quite insane, had murdered the French surgeon and stove in the chaplains head with an axe.

Knight remained on as governor at the Bottom of the Baye until 1697, before sailing for England. He returned the following year, but finally in 1700 sailed for England, apparently for good.

At this point, James Knight possessed nearly twenty-five years of experience in one of the harshest environments on the planet. It was a land where vinegar froze solid and had to be chopped with a hatchet. Good port wine froze in the glass as pourd out of the Bottle, and a red hot cannonball weighing twenty-four pounds hung next to a glass window could not keep it from freezing overnight. When summer finally came, so did the sucking insects. The terror that these creatures brought with them is apparent on almost every page of Knights diaries: Musketos & horse flyes Swarms of Small Sand flyes wch is worst of all wee can hardly see the Sun through them Our Hands and face is nothing but Scabbs. At times it was not possible for Knight or his men to even open their mouths. A twentieth-century study in this area found an exposed person subject to ten thousand bites per hour.

Men like Knight and his crews who came to this part of the world were attempting to survive in a region where even skilled Cree and Chipewyan hunters routinely starved. It was here that the Danish expedition led by Jens Munk in 1619 lost sixty of sixty-three men (amazingly, the three survivors somehow sailed back to Europe). Natives arriving the following summer encountered so many corpses that they fled in terror. It was land literally scattered with the bones of European adventurers, so much so that when Knight began construction on Churchill fort in 1717, his crew actually dug on the skeletons of those Danish sailors who had died in the previous century.