DON NEWMAN

I ts a question that continues to challenge historians, writers, and students: What is real history? Is it the grand, sweeping narratives that chronicle the major events that shaped our world? Or is it the multitude of personal tales that together weave the fabric of humanitys story?

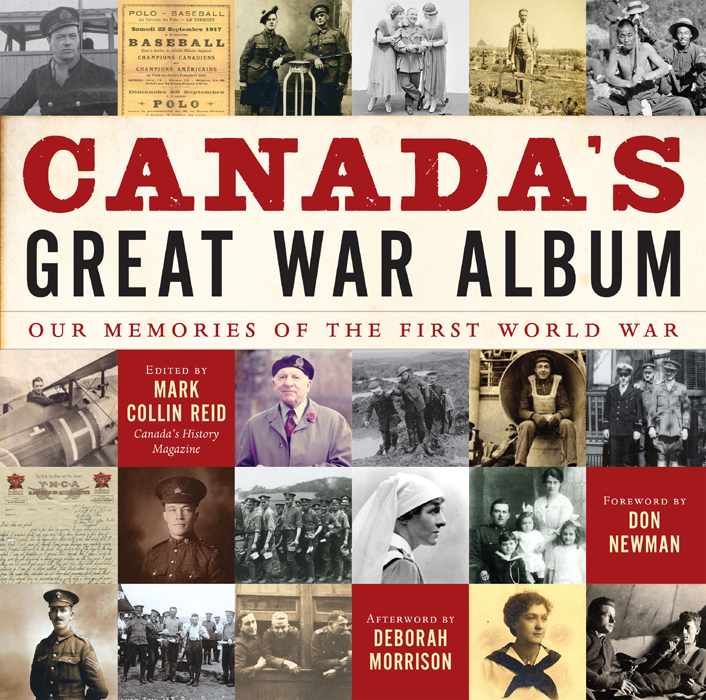

This ongoing debate was on my mind as I approached Canadas Great War Album, published by Canadas History Society and HarperCollins Canada to commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of the beginning of the First World War. I wondered: Will Canadas Great War Album settle this age-old argument, or exacerbate it?

On one hand, Canadas Great War Album offers wonderful accounts, by some of the countrys best and most respected historians, of Canadas contributions to the First World War, describing on the macro scale how the fighting unfolded and Canadas role in the conflict.

But Canadas Great War Album tells us so much more: it brings us personal accounts of the lives of the Canadians who fought in the trenches, at sea, and in the air, as well as those who served in nursing stations tending the wounded. It puts a human face on the wives and children who kept the home fires burning back in Canadathe family members who constantly feared receiving news from the front that their loved one had been wounded or killed in action. Their stories are made all the more poignant by the inclusion of never-before-seen photos and mementoes from the war.

In 1987, I became the national Remembrance Day broadcaster for CBC Television. Each November 11, for the next twenty-one years, we broadcast Remembrance Day ceremonies to the nation. Canadians everywhere were able to witness the National Act of Remembrance wreath-laying ceremony at the National War Memorial in Ottawa. And for the first few years of our broadcast, there were still First World War veterans in attendance. They were elderly, often frail, and many were in wheelchairs. But despite their advanced years, they came out, year after year, to honour their fallen comrades.

During those early Remembrance Day broadcasts, I would look at the faces of those Great War veterans and wonder what memories they were recalling.

Often, my mind would turn to the members of my own family who had served in the Great War, had survived, but whose service had taken a terrible toll. I would think of my grandfather Percy Newman, a British Army veteran who immigrated to Canada after serving in the Boer War. In Winnipeg, he started a family and ran a successful business until the collapse of the real estate market with the outbreak of war. At the age of forty-one, he again answered the call of King and country and enlisted in the Great War. He returned from the conflict wounded both physically and emotionally, ending his days in hospital and eventually dying without ever knowing any of his grandchildren, or they him.

Alan Arnett McLeod was my mothers first cousin. A native of Stonewall, Manitoba, he was only eighteen when he joined his Royal Flying Corps squadron in France in November 1917. The 2nd lieutenant quickly developed a reputation as a skilled and fearless pilot and, on March 27, 1918, he needed to be all of that and more. On that day, he got involved in a dogfight with eight German planes. During the fight, Alans plane was hit and caught fire. Pulling the plane into a glide, he climbed onto the left wing and managed to guide the burning aircraft into a crash landing.

Alan was thrown clear of the wreck, but his gunner, Lieutenant A.W. Hammond, was trapped in the burning cockpit. Despite his injuries, Alan ran back and pulled Hammond free, dragging him to safety before both men passed out. For his bravery, Alan was called to Buckingham Palace, where King George V presented him with the Victoria Cross; Alan Arnett McLeod remains the youngest Canadian ever to receive the VC.

Alan received a heros welcome in Winnipeg after he was sent home to recover from his injuries. Sadly, because of his weakened condition, in September 1918 he contracted Spanish flu. He died in Winnipeg on November 6, 1918, five days before the armistice that ended the war.

Reading Canadas Great War Album triggered these personal memories for me, and Im sure the book will have the same effect on others. The book is a testament to the courage, the pride, the sacrifice, and even the humour that our relativesjust two or three generations backdisplayed when the world seemed to go mad and dissolve into carnage.

Once you start reading Canadas Great War Album, it is difficult to put it down. And it proves that real history is not an either-or proposition. Its not grand narratives or personal stories alone. Its both, woven togethercontext and compassion, events and emotionsthat put a human face on world-changing moments.

Unauthorized cameras were prohibited in the trenches, but Jack Turner of OLeary, Prince Edward Island, broke the rule. His forbidden photographs, including this one, capture the war to end all wars in ways both poignant and frightening. Here, members of the German Red Cross carry Canadians wounded during the Battle of the Canal du Nord in September 1918.

MARK COLLIN REID

M artin OConnells attestation paper tells us many things. He had blue eyes and light brown hair, and, despite his missing two toes from his left foot, he was deemed medically fit for service. Standing five feet six inches tall and weighing 153 pounds, he was graced with a florid complexion. By all appearances, OConnell looked every inch an Irishman. But OConnell was actually a proud first-generation Nova Scotian, ready to do his bit when the call came for volunteers.

On March 4, 1916, OConnell appeared before a recruiter in Truro, Nova Scotia, and read through a gauntlet of enlistment questions: Are you willing to be vaccinated? Have you ever served in any military force? Do you understand the nature and terms of your engagement?

I wonder: Did the latter question give him pause? Did anyone on the home front really understand the nature of the savagery unfolding in Europe?

By the time OConnell stepped forward to volunteer, Canada had already suffered thousands of casualties. The patriotic fervour that had marked the early days of the First World War had cooled, and the torrent of volunteers had slowed to a trickle. The military tried new tactics to encourage enlistment; one was to create battalions tied to specific regions, so that friends and kinsmen would sign up in the belief that they would train and fight together.