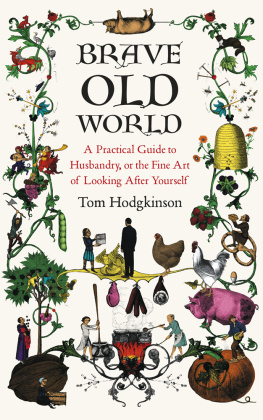

Brave Old World

A PRACTICAL GUIDE TO HUSBANDRY,

OR THE FINE ART OF

LOOKING AFTER YOURSELF

Tom Hodgkinson

HAMISH HAMILTON

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

HAMISH HAMILTON

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published 2011

Copyright Tom Hodgkinson, 2011

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book

Illustrations by Alice Smith

ISBN: 978-0-14-195265-9

By the same author

How to be Idle

How to be Free

The Idle Parent

For Alan and Alan, my husbandry gurus

We must go back to freedom or forward to slavery

G.K. Chesterton

Introduction

Labor omnia vicit

[Toil conquered everything]

Virgil

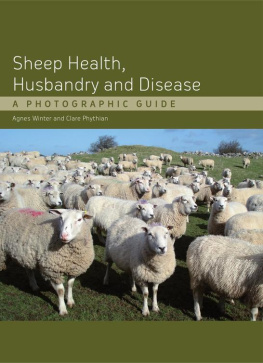

The most important but generally the most neglected of the arts of everyday living are simply these : philosophy, husbandry and merriment. Philosophy is the search for the truth and the study of how to live well. Husbandry is the art of providing for oneself and ones family, and merriment is the important skill of enjoying yourself: feasting, dancing, joking and singing.

All these aspects of life were actively cultivated in the Brave Old World. By Brave Old World, I mean the time from the Ancient Greeks to the end of the medieval period so, roughly, the two thousand years from 500 BC to AD 1500. The Old World came to an end in around 1535 with the Reformation, Calvinism, the Renaissance and the looting and smashing up of the monasteries. Philosophy, husbandry and merriment have been cultivated since, to be sure, and still are today by a few brave souls, but since the Industrial Revolution, they have tended to take second place to work for most of us, wage slavery, i.e. boring work done to enrich someone else, the corporation and its shareholders, or for the good of the bureaucratic, totalitarian state. In the Old World, cultivated leisure was the most important part of life. In the new, the job is the priority.

The art of thinking has been gradually dropped from the school curriculum. And the art of producing ones own food at home has been replaced with the chore of driving to the supermarket and buying it all. And we are the poorer for all this, not the richer.

The purpose of this book, which seeks to combine entertainment with instruction, is to examine the old ways and argue that they were often good ways, and that we could improve our lives immeasurably by adopting them in todays world. It is not for a moment intended as an exercise in whimsical nostalgia. It is clearly impossible to travel back in time; we are stuck in the here and now, and indeed there is much to be celebrated in the modern age. But fear of appearing nostalgic should not prevent us from recognizing and celebrating the good things of the past. As Ovid wrote in the Fasti of AD8 :

Laudamus veteres, sed nostris utimur annis:

mos tamen est aeque dignus uterque coli.

[We praise past ways, but use the present years, yet both are customs worthy to be kept.]

So, for example, we can sing the praises of those brilliant pieces of technology, the book and the scythe, while also enjoying the iPad or Skype, and all that modern technology which Aldous Huxley called nearly miraculous. (However, ask yourself which of the iPad or the scythe will still be around in a thousand years time.) Brave Old World focuses on husbandry, by which I mean the act of turning your household into a creative and productive entity, rather than just somewhere to watch a gigantic television screen after work. The word husband is derived from the Old English hsbonda meaning the head of the household, and the word also suggests a careful and thrifty manager. Husbandry means nurturing, that is, nurturing animals, crops, your children, yourself.

To prepare this book, I have read several old texts on husbandry, from the Greek Hesiod to the Romans Columella, Varro and Cato. Virgils great didactic farming poem, The Georgics, as you will see, is a key reference point. In the Middle Ages, there was a wonderful tradition of farming and gardening calendars, particularly in the Flemish area, and I will refer to a number of these throughout the book too. These were perpetual calendars with a special code for working out which day of the week it was, and were illustrated with lovely little pictures of medieval men and women going about their tasks. The farmer would keep one on his wall.

I have learned that books on gardening and farming are themselves a literary form : the didactic farming poem goes back to Hesiods Works and Days of the eighth century BC and probably reached its zenith in Virgils Georgics. This book is a modest contribution to that genre. Like previous examples of the form, I have quoted from the great authorities. There is the lovable Thomas Tusser, author of the Tudor best-seller Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry. Ive looked at John Evelyns seventeenth-century gardening guidebook Directions for the Gardiner, and William Cobbetts nineteenth-century The English Gardener. Another excellent find has been a medieval translation of Palladius, a Roman writer on farming and gardening who lived in the fourth century AD .

Brave Old World is in no way intended as a complete guide to self-sufficiency. It should be seen as an addition to your shelf of books on gardening and husbandry. It is perhaps more of a literary than a practical guide, though there is plenty of practical stuff in it. We stand on the shoulders of previous titans : Virgil did not feel the need to keep bees himself in order to write about them, and he referred to previous authorities in order to compile The Georgics. It is the same with William Cobbett : much of the material for his husbandry guide Cottage Economy was gleaned from an old farmers wife. And one of John Evelyns great books on gardening was itself a translation of a French best-seller, Le Jardinier franois by Nicolas de Bonnefons. Evelyn, a close friend of Charles II, also produced a brilliant gardening calendar, the Kalendarium Hortense, with the following typically extravagant seventeenth-century subtitle : Or, the Gardners Almanac, Directing what he is to do Monthly, throughout the Year; and what Fruits and Flowers are in Prime.